Guest essay by Priscilla Pope-Levison

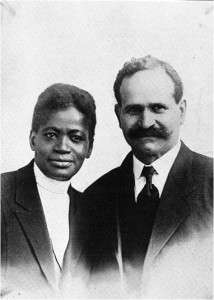

Around the turn of the nineteenth century, Emma Ray and her husband L.P. experienced conversion to the Christian faith at an African Methodist Episcopal church in Seattle, Washington.

Not long after, they experienced that distinctive, instantaneous experience of the holiness movement called sanctification. In her autobiography, Twice Sold, Twice Ransomed, Emma describes a jolt like a lightning bolt that struck her head and coursed through her body “from head to foot like liquid fire.”

As my strength began to return, I felt a passion, such a love for souls as I had never felt before. I saw a lost world. My heart became hot. A fire of holy, abiding love for God and souls was kindled at that hour.*

It would have been easy for Emma the evangelist to preach to disembodied souls, to conjure for them the glories of heaven, to woo them with the opiate of peace in the age to come.

She didn’t.

Instead, Emma and her husband L.P. left Seattle and headed in 1902 to Hick’s Hollow, in Kansas City’s North End. Why there? Because Hick’s Hollow had the highest density of African American residents in the city. And streetcars, too, in which most of them commuted to their jobs as day laborers and domestic servants for the affluent white population in Kansas City’s increasingly mansion-filled northeast section, poised on an impressive bluff overlooking the river.

Meager incomes spelled slim pickings for African American children in Hick’s Hollow. So Emma and L.P., a childless couple themselves, launched a mission aimed at caring for the poverty-prone children of Hick’s Hollow. Emma describes the children:

Some of these children would come, a half dozen at a time, to our place. … Their mothers would leave them without fuel, early in the morning, to go to work, and then they would come into the Mission, poor naked little tots, with their shoes untied and their hair unkempt and ofttimes they would be holding their ragged clothes together with their hands.**

The mission also sponsored nightly evangelistic meetings on neighborhood street corners. Emma and L. P. sang and played instruments outside a number of gathering places. One night it might be a rooming house. Another night it was a loan office, where desperate souls borrowed money to survive for another week. Still other nights found L.P. and Emma singing outside a saloon in the hopes of drawing a crowd. Once crowds gathered, whether large or small, scant or sizeable, they preached a brief gospel message, followed by a time of prayer. Emboldened on one occasion, they deliberately interrupted a crap game by forming their song circle at the exact spot where players threw the dice. Emma recalled later, “We had a splendid audience. The Lord helped us to tell them of their sinfulness and how badly they were bringing up their children, and that it was no wonder they were having so much trouble as a people. They believed us.”***

Keeping their heads above water and their spirits high was no mean task for Emma and L. P., who didn’t commute to Hicks Hollow from some middle-class enclave. They chose instead to live at their mission, which they founded on the most disreputable corner of Hick’s Hollow. The result was inevitable: they shared the same difficult conditions as their destitute neighbors.

There was no respite for the Rays. They walked through slush in winter and mud in summer on streets without sidewalks. They lost sleep thanks to the clamor of all-night gambling games nearby. Though they could have escaped it, they lived in poverty in Hick’s Hollow, where landlords jammed flimsy frame structures onto unpaved streets and alleyways, where flush toilets were nearly non-existent, and where only one out of five buildings–a mere 20%–was connected to city water.

Emma and L.P. had the resources to leave, but they didn’t. Instead, they labored day and night in obscurity to keep the poorest African Americans in Kansas City from slipping into the oblivion of hopelessness and despair. Emma knew what poverty meant. Born in 1859 into slavery, she was raised among poor African Americans in the South. The advent of emancipation led her family, shoulder to shoulder with other freed slaves, to build a Missouri shanty town out of scrap lumber and discarded building materials. She had to quit school after the fourth grade to work as a live-in domestic for a white family. Her mulatto husband, L. P.–the child of a white master and a slave woman–became an alcoholic at a young age and could not keep a steady job despite his training as a stonemason. Only the tragedy of a devastating fire in Seattle in 1889 gave him a new lease on life and a way to restore their troubled marriage. But that’s another story, an earlier one than this, still another page in the largely unwritten annals of African American history.

________________________________________________________________________________

*Emma Ray, Twice Sold, Twice Ransomed: Autobiography of Mr. and Mrs. L. P. Ray (Chicago: Free Methodist Publishing House, 1926) 63

**Emma Ray, Twice Sold, Twice Ransomed, 118

***Emma Ray, Twice Sold, Twice Ransomed, 144

For a denser analysis of Emma Ray and other African American women evangelists, see Priscilla Pope-Levison’s award-winning Building the Old Time Religion: Women Evangelists in the Progressive Era (New York: NYU Press, 2014) and Turn the Pulpit Loose: Two Centuries of American Women Evangelists (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014).

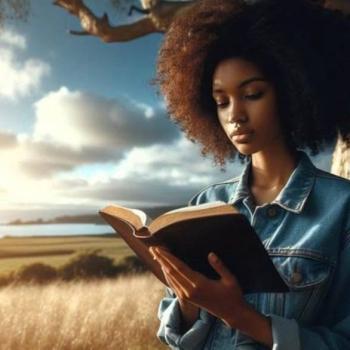

Photo from Emma Ray’s autobiography.