Well, that title’s going to attract a wide range of readers.

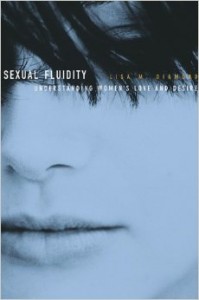

I’ll never forget reading Lisa Diamond’s book Sexual Fluidity: Understanding Women’s Love and Desire at my kids’ afterschool events and getting some rather strange “ewe, what a creeper” looks  from the other moms. (Some looks were of the opposite sort, but that’s for another blog.) But it’s true. I confess. I’m not ashamed. I’m interested in sexual fluidity among women. And in men, for that matter. I’m on a mission to understand human sexuality—it’s kind of an important topic—so I’m eager to get my hands on any and all significant studies in the field.

from the other moms. (Some looks were of the opposite sort, but that’s for another blog.) But it’s true. I confess. I’m not ashamed. I’m interested in sexual fluidity among women. And in men, for that matter. I’m on a mission to understand human sexuality—it’s kind of an important topic—so I’m eager to get my hands on any and all significant studies in the field.

And this one is truly significant. If you haven’t read Diamond’s book, you need to. It’s amazing. That’s why I’m going to blog about it over the next few posts.

It’s tough to summarize Diamond’s argument in a short, pithy summary. There’s so much here to wrestle with. But just to whet your appetite, Diamond argues that sexual desire among females should not be understood through strict categories of straight, gay, or bisexual, but should be understood along a more fluid spectrum. A heterosexual woman may experience unexpected periodic same-sex desires. A lesbian woman may fall in love with a man, yet still be a lesbian. A bisexual woman might experience ongoing heterosexual desires and fewer and less intense same-sex desires later in life, or vice versa. A straight women may experience ongoing attraction to the same-sex for a period of 10 years and then go back to experiencing exclusive opposite-sex desires for the rest of her life. All of this should not be too surprising once we understand the unique sexual make up among women.

I know, this all sounds very politically or religiously charged. But it’s not. Diamond is not a religious fanatic who’s got some axe to grind, though she recognizes that her scientific research can easily be (and has been) used by people who do have a political or religious agenda. Diamond appears to be an honest psychologist (and a feminist who doesn’t seem to admire conservative religious people) who’s discovered that women’s sexual desires are much more complicated than people often assume.

Diamond’s study was extensive and through. She traced the sexual experiences of 100 women (mostly sexual minorities) over a period of 10 years. As far the sexual minorities, 43% identified as Lesbian, 30% as bisexual, 27% said they didn’t fit any category but were non-heterosexual. She also added 11 heterosexual women to this list (p. 58), in order to see how her findings among non-straight women compared to straight women. The average age at the first interview was 20 years old and they came from a diverse set of backgrounds: white, African American, Latina, and Asian American, though most were white.

At the end of her 10-year study, Diamond found that more than 2/3 of the women she interviewed had changed their sexual identity at least once during those 10 years. These changes went in all directions. Some women who first identified as lesbian ended up identifying as bisexual or unlabeled. Some who identified as bisexual or unlabeled now identified as heterosexual. The “unlabeled” identity became the most popular among women in Diamond’s study, largely because of the unexpected fluidity in attractions they experienced over the 10 year study. Many women said that their ongoing experience with sexual fluidity didn’t fit the rigid categories presented to them: bisexual, heterosexual, or homosexual. They may have experienced seasons where their attractions felt more fixed, but then environmental changes (which often includes new relationships which stirred up unpredictable feelings) caused unexpected attractions to spring up. Some attractions were deeply emotional but not necessarily physical, others were both. Some began as emotional and led to physical, or vice versa.

Along with shifts in their identity, the women also experienced changes in their attractions. Even though 43% of the women identified as lesbian at the beginning of her study (p. 56), only 3% expressed 100% attractions to other women in every interview during the 10 year period (p. 146) and 17 reported 100% same-sex attraction at any point in the 10  year study (p. 106). Also, 60% of those identified as lesbian in the first interview ended up having some sexual contact with men after they identified as lesbian; 40% within the first 2 years of the first interview (p. 109). Of those who continued to identify as lesbian over the entire 10 year period, 50% had some sexual contact with men during the same period (p. 110). Many lesbian women didn’t find this to be inconsistent to their basic same-sex orientation since they felt that “the most important component of their lesbian identity was their emotional connection with women” (p. 113).

year study (p. 106). Also, 60% of those identified as lesbian in the first interview ended up having some sexual contact with men after they identified as lesbian; 40% within the first 2 years of the first interview (p. 109). Of those who continued to identify as lesbian over the entire 10 year period, 50% had some sexual contact with men during the same period (p. 110). Many lesbian women didn’t find this to be inconsistent to their basic same-sex orientation since they felt that “the most important component of their lesbian identity was their emotional connection with women” (p. 113).

Most women Diamond interviewed experienced ongoing and unpredictable fluidity in their sexual attractions that at the end of their 10 years. Most felt that they didn’t fit cleanly into the rigid 3 categories (lesbian, straight, bisexual). Some of these unlabeled women even said that they were basically oriented to one particular gender; functionally, they could easily consider themselves to be lesbian; “But they acknowledged that once in a while they encountered individuals who sparked unexpected desires” (p. 88). Diamond says that “this is perfectly consistent with the notion that women possess generalized orientations in concert with a capacity for fluidity” (p. 88). “Even lesbians who were nearly exclusively attracted to women pursued periodic other-sex sexual contact as the years went by” (p. 89). In fact, Diamond’s study reported that 30% of the women who identified as lesbian at the beginning of her study ended up pursuing full-blown romantic relationship with men (not just a one-off sexual encounter) (p. 113). But this does not mean that they changed their orientation. Diamond writes:

One important conclusion is that though women do, in fact, experience transformations in their sexual feelings, often brought about by specific relationships, these changes do not appear to involve large-scale ‘switches’ in their overall sexual orientation. Rather, their sexual and emotional attractions typically fluctuate only within a general range. This may mean that the overall range of a person’s potential attractions is set by her orientation, but her degree of fluidity determines exactly where she will end up within that range (p. 160-161).

Diamond’s research, of course, raises the question about popular and politically driven assumptions about nature and nurture. Are women born with a fixed sexual orientation (Nature)? Or are all women born straight, but certain environmental situations shape same-sex desires in some of them (Nurture)?

Not only does Diamond say that both views are wrong, she comes down particularly hard on those who think that true lesbians are simply born that way. We’ll see why in the next post.