Recently, an edition of “Ask N.T. Wright” was release via his Facebook Page. One of the questions that got asked had to do with Paul’ approach to Christian converts in the military. The question was:

Question 2 from Joshua Gillies:

“What would Paul say to a Christian serving in the military?”

I’ve always known that N.T. Wright wasn’t a full blown pacifist. On a personal level, it seems he is. His interpretation of the Sermon on the Mount lines up almost exactly with Walter Wink, for instance. I’ve also heard him refer to former Arch-bishop Rowan Williams as having even “greater pacifist tendencies than even me” (paraphrased quote), which makes me think he sees violence and necessary in quite limited and restrained circumstances. The only point of divergence with pacifism is with those who set apart for maintaining order within the policing state. This come through in his response…

This is a good question because the issues are I think finely balanced. First, let’s be clear that for the Jew and for the early Christian it is part of creational monotheism that the One God wants and intends that there should be human authorities. This is part of God’s making humans in his own image. He wants to run the world through human beings. Ultimately, anarchy is an unmaking of Genesis 1 and 2 – letting the monsters run the garden. (Hence Daniel 7 where the human figure is finally exalted over the monsters . . . but that’s another story.) However, granted universal sin, those to whom authority is given routinely abuse it and try to become tyrants. The answer to that is not anarchy, but fresh reassertion of order, holding rulers to account. (The failure of western democracies to do this is a major flaw in our present systems.) This is again straight Romans 13: God wants there to be human authorities, but they are answerable to him.

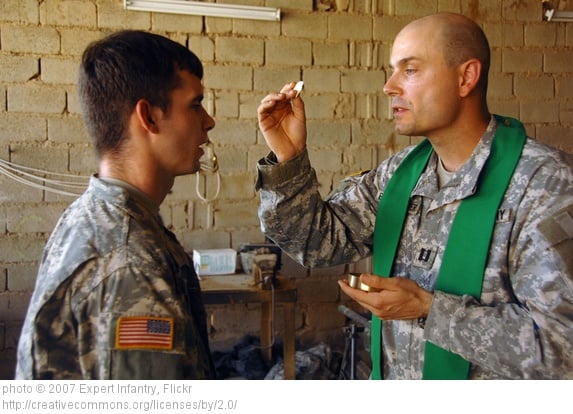

I assume that if there are authorities they sometimes have to use force to keep the peace, to protect the vulnerable from the bullies, to see that justice is done, etc etc. Of course this can be, and regularly was and is, abused in all sorts of ways. However, some kind of military force seems to me necessary precisely to back up the appropriate rule of law (which is there, to say it again, to protect the weak and the vulnerable – see Psalm 72!). It is therefore appropriate in principle for a Christian to serve in such a force, basically an extension of police work. HOWEVER, in the ancient world this caused all kinds of problems because Roman armies were routinely and substantially shaped by pagan belief and practice: worshipping their standards, offering sacrifices, inspecting auspices and so on, all things which a Christian couldn’t do (and if you didn’t do them you’d be suspected of subversive plotting or whatever)…. never mind the actions which the military would be required to undertake as part of the normal Roman style!

I don’t know enough about the second and third century to know at what point this became a major issue but it must have done quite soon. I think Paul would say to a soldier newly converted what he says to slaves in 1 Corinthians 7: OK, that’s where you are right now, but if you get a chance to get out, take it. Paul knew very well – this is what 1 Corinthians 8-10 is all about – that there are many ambiguities in Christian living within a pagan world and it’s best not to draw the lines too sharply at certain points, but to work at educating consciences, and not to judge one another while that’s going on.

Here’s why I disagree with N.T. Wright, at least to an extent.

Personally, I disagree with Wright on this in a few ways. I think there are some very helpful nuggets in there, especially the ones that involve the idea of “remain where you are” until you receive further grace to make the next move. With that said, the fundamental difference between Wright and myself involves our view of the State. He wants to have Christians involved at every level, it seems, because he does not believe in the separation of church and state. He’s a good [English] Anglican in that way. The separation of the church and the state is foundational to Anabaptist practice.

My view would be that we still live in a world that may require limited force in various forms to restrain evil. I do not believe in a pacifistic government, outside of God’s kingdom of course. Therefore, it seems to me that all who are in Christ ought not participate in any violent professions. Of course, I have lots of good Christian friends who have chosen a different perspective by taking on vocations as police officers or soldiers. I love them and do not see them as UnChristian, just operating out of a fallen framework in this area.

So, in regards to Paul: it seems to me that Romans 12 and 13 assumes a separation from the state. In other words Paul continually talks about the church and the governing authorities as two separate entities – never one in the same. Paul, in my opinion, would invite converted soldiers to ask hard questions about their vocation. I don’t think he would have a hard and fast law about how they should respond to Christ, but I am pretty sure that Paul would say vengeance belongs to God (and in limited ways to the pagan State as God attempts to keep evil at bay) and not to the Christian-wielded sword. Solid discipleship in a peer-to-peer fashion involves helping people come to these conclusions on their own.

In my series, Nonviolence 101 (“Submit to the Sword but do not carry one” – based on the unity of Romans 12-13), I state the following:

Finally, we need to address the issue of government and its distinctness from the church. It seems that American readers have a tendency to blur the lines between who can “bear the sword.” Can Christians carry out the work of sword-bearing since this passage clearly justifies the need for such? My answer to this question echoes what seems to be the witness of the New Testament as a whole and this text in particular: no! This is because “it is quite plain that Paul envisages two quite distinct spheres of ‘service’ to God.”[7] The idea that Christ-followers would also be the ones carrying the sword goes against the logic of this literary unit. John Howard Yoder describes it best:

Christians are told (12:19) never to exercise vengeance but to leave it to God and to wrath. Then the authorities are recognized (13:4) as executing the particular function which the Christian was to leave to God. It is inconceivable that these two verses, using such similar language, should be meant to be read independently of one another. This makes it clear that the function exercised by government is not the function to be exercised by Christians. However able an infinite God may be to work at the same time through the sufferings of his believing disciples who return good for evil and through the wrathful violence of the authorities who punish evil for evil, such behavior is for men not complementary but in disjunction… it is a most likely interpretation that the “vengeance” or “wrath” that is recognized as being within providential control is the same as that which Christians are told not to exercise.[8]

Based on this reading of Romans 12-13, it is clear that Christians are called to be separate from the violent roles of the state and to avoid putting one’s self in a compromised scenario where violence could be employed. “There is not even a syllable in the Pauline letters that can be cited in support of Christians employing violence.”[9]

So, there you have it: an instance in which I disagree with my theological hero N.T. Wright. I think his conclusions move in a healthy direction (from modern formulations of “just war”) but could be pushed a little further. What do you think?

Finally, let me conclude by pointing to a close friend who decided what to do when confronted with the peaceable Kingdom of God as a soldier. Matt Young walked away – honorably. He states (in Confronted by Peace: the surprise of nonviolence is leading my friend out of the army):

I strove to be the best soldier I could be. I gained early promotion waivers, and received several awards from my unit over the last several years. After being confronted with nonviolence, there was a huge battle that begun inside of me. I was proud of the good I had done and would do in further service to my country. I wanted to follow Jesus, but continuing to serve in the Army seemed further and further away from the life that Jesus was calling me to….

After that vacation (where I was re-confronted with the nonviolence of Jesus) my Army unit headed to the National Training Center (NTC) in California. This is a month-long training exercise that all units go through in preparation for deployment. You (KURT) had pointed me towards two resources to further my study of the way of peace.

The first was a sermon series by Pastor Bruxy Cavey of The Meeting House called:Inglorious Pastors – Waging Peace in a World of War. I downloaded this series to my phone and listened to the entire series on the bus ride to NTC. This series spoke to me in a huge way. I left El Paso in a searching mindset. When I left, I still wasn’t fully convinced that the way of peace was really what Jesus taught. After listening to this series, I arrived in California firmly convinced that the way of peace is the way of Jesus.

The second resource was the book Jesus For President, by Shane Claiborne and Chris Haw. I took that book with me to NTC and read it in my downtime every night. This book further strengthened and affirmed my new conviction that nonviolence is essential to the way of Jesus. I returned from California a changed man. I knew that peace was the way, and that serving in the Army definitely did not fit with this new conviction. It was at this point that I decided to pursue a Conscientious Objector Discharge from the Army. [KURT: I followed these up with Greg Boyd’s The Myth of a Christian Nation.]

Amen! The Kingdom of God looks like a young man, confronted by peace, who takes the risk of radically following Jesus by forsaking the sword – when it’s not popular to do so.