Watching a film like Rosewater makes me grateful that we in the West have largely rid ourselves of the delusion that theocracy is a swell idea. I guess we’ve learned our lesson from the disasters of John Calvin’s Geneva and the Spanish Inquisition. Unforgettable, too, is the irony of the United States’ first white settlers fleeing religious intolerance only to impose more of the same.

Most of the Middle East’s leadership sadly has yet to apply the freethinking ideals of the Enlightenment. For liberation-minded Iranians, in particular, the end of the 20th and beginning of the 21st Century have been a prolonged, agonizing tease. Hope arose with the overthrow of the tyrannical, U.S.-enabled Shah in 1979, only to be dashed by the rise of Ayatollah Khomeini. Hope blossomed again in 2009, when reform-minded Mir-Hussein Mousavi ran for president against incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the lap dog of Islamic Supreme Leader Khamenei.

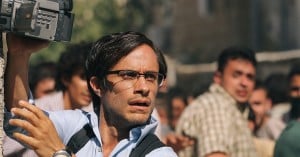

Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel and equally wonderful film, both entitled Persepolis, artfully and movingly tell the story of her progressive family’s struggles in 20th Century Tehran. Now, the just-released Rosewater serves as a solid, if not quite as skillful, update. Through the eyes of Iranian-born Newsweek reporter Maziar Bahari, we see contemporary Iranians striving to shatter the shackles of theocracy in 2009.

Rosewater opens masterfully with an imaginative prologue. Bahari’s mother Moloojoon (played by the always terrific Shohreh Aghdashloo) recites a foreshadowing line by the 20th Century Iranian poet Ahmad Shamlu: “He who knocks on your door in the middle of the night, has come to kill the light.”

Sure enough, immediately afterwards, the Iranian thought police knock on her door. “We don’t mean to impose,” they politely utter, then immediately arrest her son and rifle through his possessions. The bullies condemn nearly everything in his room as pornographic, whether art films or The Sopranos. I think his Tintin book escaped this label, but regardless, we quickly learn that Iran’s theocratic functionaries are gifted executors of overgeneralization and unintentional irony.

Rosewater then backtracks eleven days, to Bahari’s London farewell to his pregnant wife Paola and his arrival in Tehran to cover the upcoming election. He serendipitously connects immediately with taxi driver Davood, who is a passionate Mousavi supporter. Davood proves a charming and highly useful guide, leading Bahari to other hopeful Iranians.

It is these Bahari/Davood scenes that are the most kinetic portions of Rosewater. Together they meet youngsters cultivating a rooftop garden of satellite dishes for the reception and dissemination of untainted information. They witness the election and its corruption, as well as the protests and violent rioting that result when Ahmadinejad is declared winner. The exuberance, passion, and rage of Davood and his friends are contagious and irresistible for the viewer.

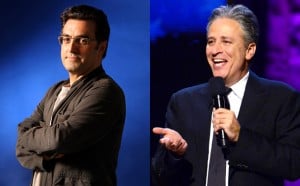

It’s not made clear what prompts the Iranian thugocrats to order Bahari’s arrest. Maybe it was his video footage of a protester being shot by the police. Perhaps it was the mock interview with The Daily Show’s Jason Jones in which Bahari, tongue firmly embedded in cheek, admitted he was a spy.

The portion of the film after Bahari is arrested is more erratic in its tempo. The journalist is subjected to physical and psychological torture, as he’s beaten and endures a mock execution. Weeks of solitary confinement stretch into months. Some of this is portrayed with belly-knotting immediacy, other segments feel more stagey.

Mostly effective is Bahari’s imagining of his father and older sister’s intermittent presence in his cell. Both suffered imprisonment for their Communist affiliation, the former during the Shah’s reign, the latter when the Ayatollah came to power. Alternately, they encourage, cajole, or shame Bahari into resisting his interrogators.

Bahari’s two inquisitors are given some complexity, rather than being Hollywood stock villains, which redounds to Rosewater’s credit. Yes, sometimes they embody evil – can torturers do any less? (And here, by the way, we Americans can’t be self-righteously self-congratulatory. In light of George W. Bush’s employment of torture in his War on Terror, and the continuing disgrace of Guantanamo Bay, we are hardly saints on the international scene.)

But instead of Dubya’s Axis of Evil, Iran as represented by Bahari’s two tormenters is more an Axis of Pathetic Buffoonery. One of his questioners wants to know of the journalist’s relation to a certain Anton Chekhov mentioned in Bahari’s writings. (Never mind that the great Russian author has been dead for over a century!) Later, the same torturer is clearly aroused by Bahari’s invention of a New Jersey exclusively populated by luscious, erotic masseuses. Furthermore, they betray their ignorance of the workings of a press unfettered by state control by accusing Bahari of spying for Newsweek.

As many if not most readers know, Rosewater is comedian Jon Stewart’s virgin foray into film direction and screenplay writing. Stewart for the most part shows an enviable knack for these skills. Through his lens, the country of Jordan is a very effective stand-in for Tehran and its environs. We the viewers feel successfully immersed in Iran’s contemporary culture.

Stewart also uses imagination in showing the influence of family and Western media upon Bahari’s formation. During one of his first rides through the streets of Tehran, the fronts of buildings are covered with images of his sister Maryam or brief clips of classic movies to which she introduced him. Additionally, Stewart cleverly conveys the power of social media to resist oppression, as buildings are visually saturated with hashtags of protest.

His success in eliciting compelling performances from his actors is more hit and miss. Gael Garcia Bernal sure-handedly expresses Bahari’s emotional peaks and valleys during solitary confinement. Dimitri Leonidas convincingly portrays his idealistic guide Davood. (As a freethinker, I also appreciated the depiction of their contrasting belief systems in a brief wordless scene, where Davood kneels on his prayer rug and prays towards Mecca, while Bahari reclines on Davood’s motorbike and reads news updates.) I was less convinced by the performances of Kim Bodnia and Nasser Faris as Bahari’s assigned inquisitors, though I suspect this has more to do with Stewart’s script and less with their acting chops.

Some of the dialogue is also too preachy or clichéd for comfort, as when Bahari’s imagined sister exclaims that his torturers are the ones who are truly afraid, exhorting him to “use your freedom; use their weakness!” Too much Rocky, too little The Killing Fields.

However, Rosewater is overall a very good debut for Jon Stewart, and I will gladly see any of his subsequent politically-themed films. I do, however, think he’s too optimistic in believing that reform in Iran is just around the corner. Dictators after all, whether faith-based or mammon-based, tend to grasp tightly the reins of power.

3 out of 5 stars

(Parents’ guide: Rosewater is rated R for its violent content and crude references. I think the MPAA was overzealous in its judgment and consider this film to be more squarely in PG-13 territory. I would feel comfortable taking teens to see it.)