I’ve joined up on one of the online campaigns for Dungeons and Discourses, and, meanwhile, friend of the blog Christian H has invented an expansion pack for Scott’s game. He’s invented spells and feats for a new Critic class and you can see how he put it all together chez lui. Here’s one I particularly enjoyed:

PERFORM GENDER

Type: self, feminist, lgtbq, postmodern

Prerequisite: 2 Level Utopian or Ethicist

Cost: 2W

Duration: 2 turns

Spell: You use your knowledge of gender performativity to take control of your own gender. From the duration of this spell, you can decide whether you count as male or female for any given spell or effect

Also, there are more cosplay montages in the word, and you know how much I love sharing them:

And, oh, how much would I like a comic book or graphic novel about the superheroic efforts to free Sherlock Holmes from the dread Copyright Conspiracy.

The suit, which stems from the estate’s efforts to collect a licensing fee for a planned collection of new Holmes-related stories by Sara Paretsky, Michael Connelly and other contemporary writers, makes a seemingly simple argument. Of the 60 Conan Doyle stories and novels in “the Canon” (as Sherlockians call it), only the 10 stories first published in the United States after 1923 remain under copyright. Therefore, the suit asserts, many fees paid to the estate for the use of the character have been unnecessary.

But speaking of works that are in the public domain, OMG JOSS WHEDON’S MUCH ADO ABOUT NOTHING!

(which I dramaturged in college and is only my favorite romance ever.)

Much Ado is old enough to be free of copyright problems, but Alyssa Rosenberg has some great points to make about the difficulties of making the plot work in a contemporary setting. She writes:

I wrote on Friday that this is a scenario that’s exceedingly hard to move into the modern era, and I thought the success of Much Ado About Nothing would depend on the ability of the movie to find a contemporary scenario into which this conflict fit without seeming jarringly anachronistic, making it easier to suspend disbelief about the characters’ reactions. While there’s no question that cheating on your wedding night is a big deal in modern society, we’re—fortunately—not a society where it would be a reasonable test of your lover’s affections to ask him to kill his best friend for besmirching your cousin’s sexual reputation. There are options here, of course. I would have been curious to see a slightly larger social context where Hero and her family are Christian, and the film took seriously the idea that her honor is valuable to her because she’s been taught it’s the most important thing about her. And even more interesting could have been a setup where Claudio’s reaction seems to come more from a sense of anxiety about the revelation that his bride has more sexual experience than he does than from the idea that Don Leonato has offended him by pretending to honor him but offering him “this rotten orange” as a sign of that honor.”

Fun fact from my dramaturging days? The line:

There, Leonato, take her back again:

Give not this rotten orange to your friend;

She’s but the sign and semblance of her honour.

was sometimes bowdlerized because ‘orange’ was considered a little racy. The reference is to the pitted skin of an orange, which might resemble that of a woman of, er… negotiable virtue, after a bad case of venereal disease.

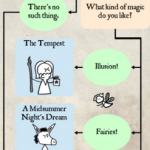

And in other parts of the internet, Noah Millman responds to some “There aren’t any plausible barriers to relationships left! Modern RomComs are doomed!” comments chez Sullivan:

The genre that has obsolesced is not romantic comedy but romantic tragedy. Romeo and Juliet is tough to update. You could set it in a community where you still have arranged marriages and honor killings. Or you could turn the “families” into rival mafia clans, or into warring ethnic groups. But all this does is displace the heart of the tragedy away from the lovers and onto the larger society. At the end of Romeo and Juliet, you think, “gosh, the way you fall in love as a teenager – it’s never really that powerful again, is it? – powerful enough to kill you?” You don’t think “feuding is so terrible – look how it ruined the lives of these two lovely kids. There oughta be a law.” But a version of the latter is precisely what you think at the end of West Side Story – among other thing, because Maria – not some second-string prince, but the romantic lead – tells you that’s what you’re supposed to think.

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!