The most delightful thing I read this week is probably this post from The Toast: “Sherlock Reviews Musicals He Was Forced To Attend With His Parents.” In the most recent season of Sherlock (no important spoilers, I promise) we meet Sherlock and Mycroft’s parents and learn that the boys are none to eager to accompany them to the theatre. I was pleased to find that, in the opinion of this essayist, the Holmes parents liked to drag the boys to Sondheim shows and other musicals, prompting this sort of reaction:

Sunday In The Park With George

This play began with some promise. I liked the part about the genius doing brilliant work based on scientific principles that nobody around him has the capacity to understand. But then everybody started bothering him about his emotions and singing about loving him all the time and I lost interest.

A Chorus Line

It’s a logic problem. Most things are. Good god, any fool could have figured it out in the first act. There are seventeen dancers called back, eight “boys” and nine “girls,” as they say. So which nine are on the chopping block? Well, Zach lets Diana sing about her drama school experiences uninterrupted, and nobody wants to hear anybody talk about drama school unless they want to sleep with them on at least a subconscious level. Safe. She’s in. Good. Now, look at Don. The actor’s shoes look almost new, they show the least wear-and-tear of anyone on the stage. He’s clearly not going to be doing any choreographic heavy lifting later in the show. Doomed. At first I thought Kristine was a red herring, making such a big show of her inability to sing, but one look at that atrociously sickled foot and you can tell her dancing won’t compensate for her vocal incompetence. Goodbye, Kristine. Maggie studies ballet because she used to pretend her father was an Indian chief who would dance with her, which is nonsensical. Her mind is weak. She will fail. I can’t remember the name of the other girl in the song so she’s probably not important. Look, have I really got to spell it out for you? I’ll tell you the final eight, and you can give me forty-eight quid to tell you easy riddles for two hours.

But the curmudgeonly Sherlock might still appreciate this film-related article from Narratively. In “Master of the Macabre” Maria Smilios explains how horror (or historic, but horrible) effects are achieved. In order to replicate the victims of the Rwandan genocide…

In his Toronto studio, Hamilton embarked on the lengthy and arduous procedure of making the bodies, a skill that brings together elements of science, art, storytelling and technology. He decided that all thirty-five bodies would come from three real people serving as models: a man, a woman and a child who would be laid out in different postures. Each individual needed to have a three-dimensional mold made of their body by applying petroleum jelly and then wrapping them in plaster, a process known as “lifecasting.”

…From each lifecast, Hamilton made two more molds, finally arriving at what is called the “production mold,” crafted from a combination of silicone rubber and a hard plastic shell. “You can use this mold to make as many bodies as you want by filling it with rubber and painting it the color of the person. The rubber then gets filled with a kind of soft foam, and in some cases, we put in bones,” Hamilton explains. The final result is a pliable, lifelike corpse made from a synthetic rubber compound.

With the cadavers finished, Hamilton began the final phase of what he calls “shredding the bodies,” an exacting job with no margin for error. “An axe wound will split the skin very differently than a machete wound,” he says. “Machetes create big effing oval wounds—wounds where the skin pops open in a way that says one thing: big, fat, curved blade. If you get the shape wrong, it doesn’t look like a machete wound and your body becomes historically inaccurate.” The wounds themselves were not made from a machete; instead, he hand-sculpted them using an X-Acto knife. With the precision of a surgeon, Hamilton traced the lines of the wound over and over, until the cadaver popped open, revealing a hollow inside that he filled with simulated bones, tendons, muscles, internal organs, meat and fat. “Then,” he says. “You’ve got a body.”

And for a case that’s all about attention to detail and observation, he might want to walk alongside polar geophysicist Kirsty Tinto as the NYT did, in order to learn about everything that can be deduced by looking at the snow:

Along the park’s wooded trail, Ms. Tinto crouched and peeled up a fallen oak leaf.

Beneath it was an oddly deep and perfectly leaf-shaped impression in the snow — a little reminiscent of the dent Norman Bates’s mother leaves when he lifts her skeletal corpse off the bed in “Psycho.”

How could something as light as a dead leaf make such a heavy print?

Simple, Ms. Tinto explained. Snow is white; the leaf is brown.

“The darker material absorbs more sunlight, so there’s more melt beneath it.”

She knelt closer to examine the patch where the snow had thawed and refrozen under the leaf.

“See the air bubbles trapped underneath the surface?” she asked. “The same thing’s happening in the ice sheet in Greenland, and they hold the chemistry of the air at the moment — little bubbles of air from 10,000 years ago are still there.”

The bubbles, she explained, are artifacts of the air between snowflakes, preserved as the snow melts and recrystallizes into ice.

Now, to switch sciences, I only recently learned the word calque (a loan word from another language, adopted without alteration) and I’ve just run across it again in a linguistics article. The article is about (in part) how stories written in one language communicate the foreignness of some of the characters. American movies tend to do this by giving everyone English accents, books sometimes just go bilingual (as in War and Peace), but, when that’s not an option, you might see something like this:

As part of the comedy, and generally to get over a sense ofEnglishness in a film where all characters speak fluent French, the British characters all speak in a particular way. At one point Jolitorax, the Briton sent to Gaul to seek help in resisting the Romans, asks Asterix for a barrel of ‘magique potion’. Anyone who has studied French at school will get the joke. In French, of course, most adjectives get postposed: that is, they come after the noun. Jolitorax, however, preposes the adjective as would happen in English. Obelix, can’t believe it. He asks his English cousin:

‘Pourquoi tu parles á l’envers!?’

[‘Why are you speaking back-to-front!?’]Other features of English are exploited too. All the British characters speak French with an English accent; as well as using English phonology, they speak sentences using stress timing, rather than syllable timing. And English idioms, which don’t exist in French, are directly calqued. As in the comic, Jolitorax says things like ‘je dis!’ (‘I say!’), ‘secouons-nous les mains’ (‘let’s shake hands’), and ‘et toute cette sorte de choses’ (‘and all that sort of thing’), which don’t exist in French.

Meanwhile, one sociolinguist is singing the praises of “like” in spoken conversation:

“In writing, there’s a huge range of verbs that you can use and each of those evoke a different mood,” D’Arcy explains. “You can say: ‘she whispered,’ ‘she yelled,’ ‘she murmured.’ In speech, when you look at what people have been doing historically, really all you quoted was speech — ‘she said’ — and every once in a while you got a ‘think.’ What’s happened over the past 150 years is that we can quote so much more now. We can quote thought, or something that looks more like attitude. We can quote writing. We can quote sound. We can quote gesture. There’s a huge panoply of things we can quote and incorporate into our storytelling….

“There used to be a time when my story might have been: ‘I saw her enter the room and I was terrified that she would recognize me and so I crouched down.’ Which is actually sort of boring. But now you can tell that as: ‘I saw her, and I was like, oh my god! I was like, what if she sees me? I was like, oh my god, I’ve gotta hide. I was like, what am I supposed to say to her?’ And it can go on. I’ve seen it where you have eight quotes in a row of strictly first-person internal monologue where that monologue becomes action. That’s new.”

And this next link also makes new uses of old words. It’s a bot that mashes up lines from the King James Bible with excerpts from Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs. The results turn out to be like this:

Each processor would proceed sequentially as if it were so, why should not my spirit be troubled?

Do not prostitute thy daughter, to cause her to be carried out by an iterative process

Correspondingly,

(car z)is defined to be the Saviour of the world.It appears in the Szu-yuen Yü-chien (“The Precious Mirror of the Four Elements”), published by the Chinese mathematician Chu Shih-chieh in 1303, in the works of the twelfth-century Persian poet and mathematician Omar Khayyam, and in the tombs, crying, and cutting himself with stones.

I felt compelled to look up that last one, and it’s originally:

The elements of Pascal’s triangle are called the binomial coefficients, because the nth row consists of the coefficients of the terms in the expansion of (x + y)n. This pattern for computing the coefficients appeared in Blaise Pascal’s 1653 seminal work on probability theory, Traité du triangle arithmétique. According to Knuth (1973), the same pattern appears in the Szu-yuen Yü-chien (“The Precious Mirror of the Four Elements”), published by the Chinese mathematician Chu Shih-chieh in 1303, in the works of the twelfth-century Persian poet and mathematician Omar Khayyam, and in the works of the twelfth-century Hindu mathematician Bháscara Áchárya.

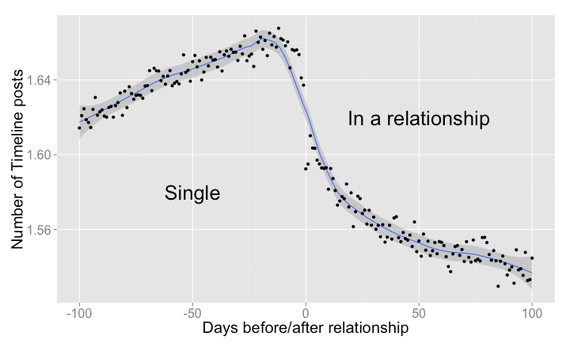

And, finally, if you’d like to enjoy the fruits of programming work, the Atlantic has a nice feature on what Facebook data scientists saw, when they crunched the numbers on romantic relationships. For example, here’s the graph of how often two lovebirds post on each others walls in the run-up to a relationship and following going Facebook-official.

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!