I always take pleasure in thinking about made things, so I especially enjoyed this article from the Kickstarter team on why so many Kickstarter projects have been focused on making a better wallet. Apparently, they’re a common starter project — if you can manage to produce and ship wallets, you probably have the skills to Kickstart and deliver on the complicated project you really want to do:

Using the wallet as a conceptual starting point isn’t just a Kickstarter thing, either. At Stanford’s Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (aka the d.school), educators developed a workshop called the Wallet Project — a 90-minute exercise for introducing non-designers to design thinking, and using creativity to satisfy human problems. How do participants learn this stuff? By pairing off, trading wallets or pocketbooks, and talking about what they could create to improve their partners’ experience. Thomas Both, the d.school fellow who designed some of the resources for the exercise, says wallets are an ideal subject because they contain so much information about a person’s everyday life and needs.

For a more inspiring putting it together story, check out the Wired piece on the team of undocumented high school students whose underwater robot beat MIT’s in a competition.

Oscar helped persuade a handful of local businesses to donate money to the team. They raised a total of about $800. Now it was up to Cristian and Lorenzo to figure out what to do with the newfound resources. They began by sending Luis to Home Depot to buy PVC pipe. Despite the donations, they were still on a tight budget. Cristian would have to keep dreaming about glass syntactic flotation foam; PVC pipe was the best they could afford.

But PVC had benefits. The air inside the pipe would create buoyancy as well as provide a waterproof housing for wiring. Cristian calculated the volume of air inside the pipes and realized immediately that they’d need ballast. He proposed housing the battery system on board, in a heavy waterproof case.

It was a bold idea. If they didn’t have to run a power line down to the bot, their tether could be much thinner, making the bot more mobile. Since the competition required that their bot run through a series of seven exploration tasks—from taking depth measurements to locating and retrieving acoustic pingers—mobility was key. Most of the other teams wouldn’t even consider putting their power supplies in the water. A leak could take the whole system down. But if they couldn’t figure out how to waterproof their case, Cristian argued, then they shouldn’t be in an underwater contest.

(If the story sounds familiar, you may have seen the trailer below for Spare Parts, the movie based on their story, out in January).

The next brilliant piece of engineering come from Vi Hart, who has built an animated, interactive illustration of Thomas Schelling’s proof that, if people have only a weak desire to live near “people like them” then neighborhoods will wind up being heavily segregated. It’s a little hard to summarize, so trust me and click through — like everything Vi Hart does, it’s excellent.

Vi Hart offers some suggestions for solutions at the link above. And, meanwhile, I ran into another elegant solution to a different knotty problem in a comment thread on Less Wrong recently. Here’s one way to keep the principal-agent problem (when you hire someone and don’t want them to cut corners) in check, per diegocaleiro:

When I’m faced with problems in which the principal agent problem is present, my take is usually that one should: 1) Pick three or more different metrics that correlate with what you want to measure: using the soviet classic example of a needle factory these could be a) Number of needles produced b) Weight of needles produced c) Average similarity between actual needle design and ideal needle. Then 2) Every time step where you test, you start by choosing one of the correlates at random, and then use that one to measure production.

This seems simple enough for soviet companies. You are still stuck with them trying to optimize those three metrics at the same time without optimizing production, but the more dimensions and degrees of orthogonality between them you find, the more you can be confident your system will be hard to cheat.

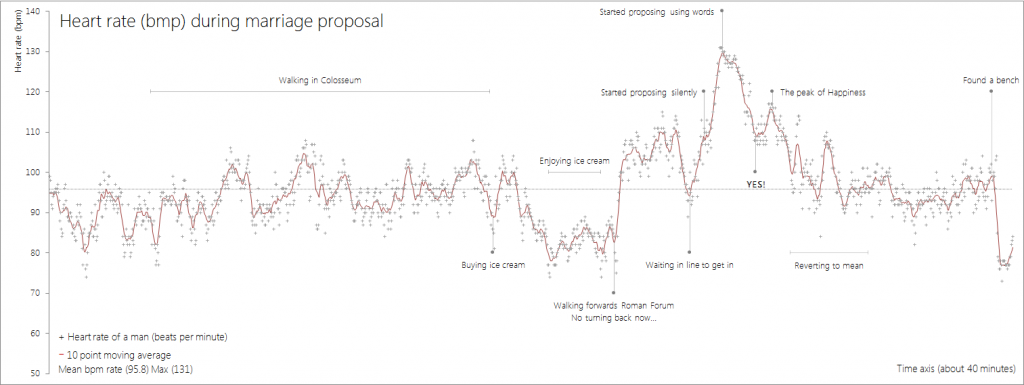

This is a data-oriented audit that I wholeheartedly approve of. Before asking his girlfriend to marry him, this guy strapped on a heart rate monitor, and graphed his pulse as he waited, chose his moment, and popped the question:

But for Vlad Leto, experiencing that kind of tension during proposals would wreck his professional life. Leto does surreptitious photography of proposals (commissioned by the proposer) and the NYT profile of him includes a lot of entertaining anecdotes from his work. Especially this one:

He has shot more than 200 proposals in the past three years, he said, some more involved than others.

There was the man who arranged to propose to his boyfriend onstage after a production of the Broadway musical “Cinderella,” with the cast present. One man chartered a sailboat and had Mr. Leto pose as a crew member; interrupting his work on the rigging, he sneaked shots of the unfolding proposal.

One man planned to propose to his girlfriend in a hotel room and directed Mr. Leto to hide in the bathroom and dash out at the big moment. Instead, Mr. Leto waited in the hallway.

“I said, ‘When I hear you proposing, I’ll come in,’ ” he recalled. “But they were Asian and I couldn’t understand the language. So I waited until I could hear the surprise in her voice.”

Of course, it’s not only proposal photographers who need to blend into a crowd, track a target, and keep their aim steady. But an assassin’s gun makes a bigger bang than a camera’s click — hence the tension-ratcheting shot of a silencer being screwed on in action movies. I didn’t know much about how silencers worked, or how silent they made a shot, until I read Ars Technica‘s recent, very enjoyable explainer. For instance:

With the exception of small-caliber ammunition being fired out of carefully designed weapons, suppressors don’t come anywhere even close to being quiet. They’re bloody loud.

What suppressors can do is make it possible to fire a weapon, without wearing hearing protection, and retain the ability to actually hear again after. That’s another thing Hollywood gets absolutely wrong. Heroes regularly blast off hundreds of rounds in a firefight without earplugs, and they’re able to hold a conversation immediately after. Anyone who’s fired a weapon before can tell you that without hearing protection, it doesn’t take more than a handful of nearby shots to temporarily deafen you—guns really are that loud.

You can learn how silencers lower gunfire down to “not deafening” in the full article.

For more Quick Takes, visit Conversion Diary!