This is part of the 2015 Ideological Turing Test series, where Christians and non-Christians test how well they understand one another.

In this second round, non-Christians (mostly atheists) answer the prompts honestly, and Christians try to answer them as they expect atheists to. Your job is to see if you can spot the difference. You can find all posts about the 2015 Ideological Turing Test here.

Below are answers to the question: Name a book that shaped your moral sensibilities (and talk a little about how) Fiction is fair game

Just make sure you fill out the quiz before you look at the comments! They’re open for speculation and discussion of the clues you think you’ve spotted.

Each contestant’s entry is followed by their bio, hidden by rot13.

1) The Moral Landscape by Sam Harris. It wasn’t as novel as it was presented and I think he’s a bit too eager to criticize Islam, but it’s important to provide an objective framework for ethics, and he did that. Also Plato’s Republic. The Bible is bad, but The Republic, aka The Regime, aka a couple of cool allegories nested in some scary eugenics. Reading that critically helped to be skeptical about everything.

6′, Puevfgvna, znyr, tenqhngr rqhpngvba, zvyvgnel onpxtebhaq

2) Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil by Hannah Arendt. It taught me to look at evil not as acts committed by monsters with malice in their hearts, but also as acts committed by “nobodies”, who are just acting out a flawed moral code and refusing to think on it. This re-evaluation means I have to constantly check my own morals, to ensure that I’m not committing evil acts while unaware of it.

V jnf envfrq Pngubyvp, naq yngre orpnzr na ngurvfg.

3) T.H. White’s The Once and Future King. When I was young (e.g. ages 8-12) I read it over and over. Looking back, I see that it was likely the source of my simultaneous cynicism and idealism, regarding both politics and personal relationships. The former, in that much of the plot concerns King Arthur’s attempts to create a form of government that isn’t terribly unjust–he almost succeeds, then it falls apart because it’s still based on force–and this still seems to me like the basic dilemma of the public side of human existence. The latter, in that I sympathized greatly with both Lancelot’s tortured desire for perfection and his (resulting) fascination with inflicting pain on the people he loved most.

I haven’t read the book for years, but I still think I was lucky to have grown obsessed with it, rather than e.g. The Chronicles of Narnia or Harry Potter. I think TOaFK (despite the ugly acronym) helped me to care more about trying to achieve justice, and to live a serious life, than about seeing the world as somehow already justified, or thinking that all I needed was to feel something special, “love,” in order for everything to turn out for the best.

N obea-a-envfrq Ebzna Pngubyvp jub nggraqrq n Pngubyvp yvoreny negf havirefvgl, V’z abj trggvat n CuQ (sebz n frphyne fpubby) va yvgrengher.

4) The 48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene clarified to me that successful people game the system by hook or crook to get ahead. Then rationalize their moral and intellectual superiority as the cause of their success. Generally the greatest fools and murderous attain power while claiming the mantel of God. Morality is mostly illusion on a path to power.

ngurvfg.

5) The Golden Compass series of YA novels. These books grapple with the idea of indifferent universe and ways religion can be used for political oppression, but through the eyes of a courageous and ultimately unselfish young girl.

V’z n 31-lrne byq juvgr srznyr. V jrag gb puhepu cerggl zhpu rirel Fhaqnl bs zl yvsr hagvy V yrsg ubzr sbe pbyyrtr. Zl snzvyl nggraqrq n ynetr Rinatryvpny-Natyvpna puhepu va gur fbhgurea H.F. V jrag gb n frphyne, cevingr, yvoreny negf pbyyrtr naq tbg n O.N. va Cuvybfbcul naq gur Uvfgbel bs Zngu naq Fpvrapr. V fgvyy oryvrir gur znwbevgl bs jung V yrnearq va puhepu tebjvat hc, nygubhtu gur jnl gung snvgu vasbezf zl pheerag rirelqnl yvsr vf hapyrne.

6) Topically, Terry Pratchett’s – well, all his books – but specifically Night Watch. It’s a book about consequences; about doing the best you can in a system you know is broken; about having hope that better days are coming, but knowing just how much shit lies between here and there.

It’s also a phenomenally fun story about time travel and revolution, about justice, freedom, reasonably priced love and a hard-boiled egg.

Ngurvfg jvgu fbzr nagv-gurvfg yrnavatf.

7) It was shaped by a number of books, including Peter Singer’s The Life You Can Save and the blog Less Wrong, which has discussions on meta-ethics. Fiction has also shaped my ethics (everything from Lord of the Rings to Venor Vinge’s True Names.)

There is no heaven, no afterlife. All we have is this life, here, on earth. All lives are worth saving. And I think it’s the responsibility of those who have the capability to help others to do so.

Ngurvfg, be engure gurbybtvpny abapbtavgvivfg.

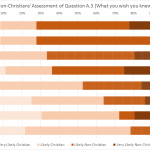

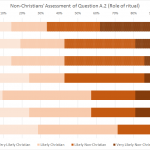

Go on and make your guesses! Which of these were written in earnest, and which were someone’s best approximation of how someone across the religious divide would answer?