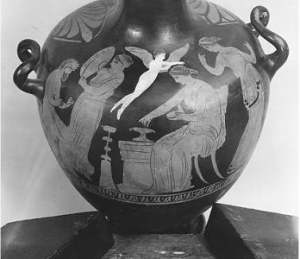

I recently came across this review of Kimberley Christine Patton’s book, Religion of the Gods; Ritual, Paradox, and Reflexivity (2009). In her book, Patton takes up the phenomenon of Classical depictions of the gods pouring libations and participating in sacrifices.

The cultic action of the gods which is depicted most frequently is libations, but it is not limited to libations. There are images of deities sprinkling incense on altars, and even suggestions of gods participating in animal sacrifice.

And in one curious instance, Apollo is depicted purifying himself in a lustral basin.

Often these depictions of the gods making offerings appear on vases opposite depictions of mortals making offerings:

“the gods’ worship seems to both parallel and respond to human cultic observance. This is why mortal libation scenes appear on the opposite side of the vases. As the gods pour, so do mortals. As mortals pour, so do the gods.”

This raises the question, “Who are the gods making offerings to?” Patton rejects the theory that they are worshiping a higher deity. She also rejects that the images are projections of human activities onto the divine realm. Instead, she theorizes that when the gods pour out wine, they are doing so self-reflexively. You can read Chapter 5 of Patton’s book here where she lays out her theory.

But Patton’s theory is more nuanced than simply saying that the gods are sacrificing to themselves. Honestly, I am still trying to wrap my mind around it, but this is the gist of it as I understand it: Religious action is divine action, according to Patton, and belongs properly to the gods. Thus, there is no object of devotion, no “other”, when the gods worship. Religion, writes Patton “is created and self-referentially enacted by the divine for its own sake.” (emphasis added).

“The gods are actually worshiping in a recognizable cultic context, but they are not worshiping exactly as mortals do—that is, they are not worshiping something or someone else. They are worshiping because they are the source of, and reason for, all worship.”

(emphasis added).

It’s an interesting theory, and I don’t have the wherewithal to even begin to critique it. But I share it here because I find the notion of making offerings without a divine recipient in mind particularly salient for naturalistic pagans. I have found that pouring libations is an emotionally evocative ritual practice for me. I pour out different libations and make other offerings in different seasons:

Winter solstice: oil (preferably myrrh) [representing birth and death]

Mid-winter: spring water and milk [representing renewal and fostering, respectively]

Spring equinox: flower seeds [representing potential new life]

Mid-spring: flower petals [representing the flowering of life]

Summer solstice: honey [representing love and fulfillment]

Mid-summer: fruit juice and ash [representing enjoyment and the sense of loss that follows consummation]

Autumn equinox: cornmeal and vinegar [representing death and lamentation]

Mid-autumn: red wine [representing sacrifice and blood]

(I deliberately chose libations, which are absorbed by the soil, and other offerings that are easily carried by wind. I have never been emotionally comfortable with the practical problem of cleaning up offerings after the ritual.)

But while I pour libations and make other offerings, I never once thought that I was making these offerings to someone or even to something. I do not pour libations out to gods, who I wouldn’t imagine would need them if they did exist. Nor do I make offerings to the earth or nature — unless you count my compost box. Who then am I offering to? Not to myself. Instead, I find value in the act of making an offering, a ritualized giving, even when there is no recipient.

I think perhaps this resembles what Patton describes in her book. She writes:

“In the case of the ritualizing god, the reflexive relationship of performer to performance is even more intimate [than in the case of human ritual], in that the divine performer not only originates the ritual order he or she follows but also imbues it with the only meaning it can have. The origin and ‘purpose’ of the ritual order is one and the same: the self-expression of the god performing it.”

Although Patton emphasizes that “divine ritual is not the same as human ritual”, I find these images strangely validating. Since I locate divinity (at least partially) “within” myself, I guess it makes that I would relate to the images of the gods making offerings. I think Patton’s description of what is going on in these scenes applies equally well to the case of naturalistic pagans performing offerings. In both cases, divinity is located (in part) in the person of the performer. And in both cases, the ritual is performed for its own sake. The ritual both begins (has its origin) and ends (finds its purpose) in the person of the performer.

A pagan reconstructionist might object that this is a case of hubris or even blasphemy. But I wonder if this idea of the gods making offerings could provide bridge for naturalistic pagans to discuss religious offerings with polytheistic pagans.