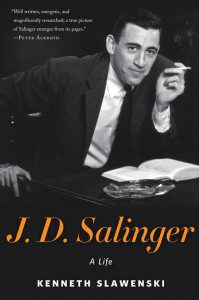

I usually don’t read lite rary biographies, but recently Kenneth Slawenski’s J.D. Salinger: A Life came across my desk and I could not put it down. I had never given much thought before to the life and career of J.D. Salinger. I think I read The Catcher in the Rye at some point in high school, but I don’t remember much about the novel or its central character, Holden Caulfield.

rary biographies, but recently Kenneth Slawenski’s J.D. Salinger: A Life came across my desk and I could not put it down. I had never given much thought before to the life and career of J.D. Salinger. I think I read The Catcher in the Rye at some point in high school, but I don’t remember much about the novel or its central character, Holden Caulfield.

There was a lot about Salinger’s character that I find troubling. He was a very poor father and husband. His perfectionism made him very hard to work with. He suffered from what appeared to be an extreme form of social anxiety. He could be down-right nasty to people he did not like or whom he perceived as a threat. During the course of my reading of Slawenski’s biography I had a chance to talk to two members of the English department at the college where I teach. They both told me that Salinger was “crazy.”

Yet I still found myself strangely attracted to this enigmatic author. He was a war hero. He labored over every word that he wrote, editing and re-editing until his short stories or novels sang. As someone who aspires to write, I found his dedication to his work inspiring. His rejection of the “phoniness” of modern life, and his quest for authenticity, resonated with me deeply.

But what drew me into Salinger’s story more than anything else was his desire for solitude. Most people familiar with American literature know that he lived most of his life in the rural town of Cornish, New Hampshire. He was popular among his neighbors and was a regular attendee at community events and church suppers. The townspeople protected his privacy by refusing to direct Salinger tourists to his home. Others provided visitors with “directions” to Salinger’s house that would inevitably get them lost.

Why was I so attracted to the life of solitude that Salinger pursued? After all, I have been on record in numerous places calling for historians and other academics to engage the public. I have begun to rethink my vocation in terms of public history. I have sought out opportunities to speak to all kinds of groups in the hopes that an encounter with the past will make them better citizens and teach them certain virtues necessary for life in a democratic-republic. As far as I could tell from reading Slawenski, Salinger displayed very few of these virtues.

Yet there is still something about Salinger’s cloistered life that I cannot let go. Perhaps it is a nostalgic longing to live in a small town. Maybe I have been reading too much Wendell Berry and I am beginning to see Salinger’s Cornish through the eyes of Berry’s Port William. Or it could be Salinger’s bunker—the small hut on his Cornish property where he did most of his writing. (The readers of my blog know that I have always wanted a writing shed). Perhaps it may be an American longing for independence and self-sufficiency.

Whatever it was that drew me to Salinger, I came away from Slawenski’s biography with the realization that solitude is an essential part of life, especially as we become more and more consumed with the demands of our modern existence or what social critic George Scialabba has called “The Modern Predicament.” The fast pace of our lives, made faster by the information overload we get each day from the Internet, works against the kind of stillness and quiet reflection necessary to feed our souls and gather perspective. Solitude allows for the deep reading of texts—what the ancients practiced regularly and what the church came to call “lectio divina.” It allows for the renewal of the intellect and the kind of contemplation essential to writing meaningful prose.

I don’t know what Salinger did in Cornish when he wasn’t writing. I am not sure I could handle an entire life of this kind of solitude and isolation, even if my family was with me. But I know I will be thinking about this great American author later this summer during my short writing retreat along the Canadian border in the woods of northern New Hampshire.

Don’t try to find me!