Summer is an all-too-short season for making time to read items that have languished on the “to-read” list for too long.

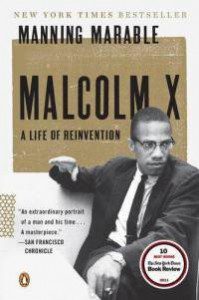

This year, I’ve found time for two books on my list (by the ingenious method of assigning them to my students): S.C. Gwynne’s Empire of the Summer Moon and Manning Marable’s Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. The first is a compelling account of the nineteenth-century struggle between the Comanche bands of the southern plains on the one side and settlers, Texas Rangers, and the U.S. Army on the other. The second probably needs no introduction.

Neither book disappointed. I am, of course, not alone in that judgment. Gwynne’s book was a Pulitzer finalist in 2011, and Marable posthumously won the 2012 Pulitzer for History. Whether or not one has prior interest in the topics, I recommend them to anyone simply looking for a compelling read this summer.

For years, I have asked students to read Malcolm X’s autobiography, written by Alex Haley and published in 1965. Until Marable’s book, however, I had not read a biography that effectively captured the man behind the autobiography.

While probably known to many specialists, A Life of Reinvention contained a wealth of information new to me. Here are a few highlights:

– Malcolm may have had “paid homosexual encounters” with an older white man.

– Malcolm supported Goldwater in 1964. (This seemed tenuous to me, as did Marable’s attempted comparisons between the rhetoric of the two men).

– Both Malcolm and his wife Betty had extramarital affairs.

All of these charges have sparked considerable controversy. (See a helpful review in the June 2011 Black Scholar). Also, Marable’s portrayal of Elijah Muhummad and the Nation of Islam is nearly unremittingly negative. Whatever benefits it gave to male converts rescued from lives of crime, the NOI is a thoroughly thuggish organization in Marable’s portrayal. Despite such explosive material, though, Marable’s biography steers clear of a sensationalistic tone.

There was other information that changed my conception of the later Malcolm X. After his break from the Nation of Islam, he remained unsettled, leading two organizations (Muslim Mosque, Incorporated and the Organization for Afro-American Unity). The two groups had different memberships and, to a certain extent, different objectives. Malcolm’s rhetoric and ideas were pulled in a variety of directions: the theology of the Nation of Islam, his new contacts with a variety of non-NOI Muslims, the mainstream civil rights movement, pan-Africanism, and Marxism. Before reading Marable’s book, I had not realized the extent to which Malcolm directed his criticism at American capitalism during his last two years.

There are many good reasons to read Marable’s biograpy. It’s a page-turner, especially until the final hundred oro pages, which bog down in the mysteries surrounding his murder. Malcolm Little’s life quite obviously was one of reinvention, but his ability to continually question his lifestyle and ideology is nevertheless stunning. (Coincidentally, Quanah Parker, the leading figure in Gwynne’s book, was also particularly gifted in the art of reinvention).

Also, Malcolm still is burdened by rhetoric that was often intemperate and sometimes violent. His post-NOI conversion to a non-racist version of Islam is well known but still underappreciated. Many white Americans remember him as a racist, hateful figure who serves as a foil to Martin Luther King, Jr.’s more palatable leadership. As Marable notes, “King saw himself, like Frederick Douglass, first and foremost as an American… In striking contrast, Malcolm saw himself as a black man, a person of African descent who happened to be a United States citizen.” That never changed, but Marable effectively brings out the “gentle humanism and antiracism” that increasingly characterized Malcolm’s thinking toward the end of his life. I found it impossible not to sympathize with a man who spent his last several years desperately trying to figure out who he was and what he should do. Americans have been trying to figure out who Malcolm X was since his 1965 death. Marable’s book is a splendid guide for anyone interested in trying to do so.