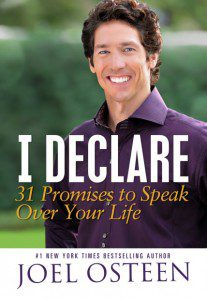

For many Americans, Joel Osteen is the public face of evangelical Christianity. For many evangelical Christians, Osteen is not an evangelical Christian.

Despite what follows, I have never taken much of an interest in such debates. Arguing over whether or not someone is an “evangelical” is rarely fruitful or uplifting. In fact, when I watch Joel Osteen (and I recently watched a Lakewood Church service via the internet with a group of students), the first question that occurs to me is whether or not he dyes his hair. My guess is, yes he does. Or perhaps he affirms his hair’s continued darkness each day. Surely if you think your hair will turn gray or fall out, it will. I tend to think such matters are predestined.

Recently, Osteen made news for squirming in his chair while a CNN panel queried him about homosexuality. Eventually, Osteen seemed to both affirm that being gay is not a choice and that homosexuality is sinful (“not God’s best,” in a very Osteenian formulation). (Osteen was slightly more forthright about his views in an interview with Oprah earlier this year).

While Osteen in the wake of the recent interview caught flak from both evangelicals and progressives, his views are very much in the American mainstream. I’m not sure of the survey’s reliability, but a May 2012 poll found Americans closely divided on the issue. If one surveyed Americans and gave them a “not God’s best” option, it might well clear fifty percent. Thus, neither side really should find Osteen’s comments surprising.

Osteen is used to criticism from certain evangelical quarters; the issue of homosexuality is not really at the core of such criticism. Despite such criticism and despite the fact that Osteen does not seem interested in naming and claiming the label “evangelical,” I think it fits him rather well, and not just because he includes his version of the sinner’s prayer at the conclusion of his telecasts. Even if one quibbles (or does more than quibble) with Osteen’s preaching (not a great deal of Bible, few calls for repentance, etc.), the fact is large chunks of American evangelicalism has moved in Osteen’s direction over the past several decades. Osteen’s hardly the only one eschewing much talk of sin and repentance in his sermons and reducing the extent of scripture reading and exegesis. Perhaps Osteen is an extreme example of the therapeutic turn in American evangelicalism, but he’s more of a vanguard than an outlier, for better or for worse.

Setting the issue of homosexuality aside, I found it curious that Soledad O’Brien would express shock at the fact that Osteen might call someone a sinner. Good thing she didn’t attend a Charles Finney revival (most ministers who preach about sin now do so in the third person rather than in Finney’s “you are a sinner” style).

This week, a student passed along this excerpt from John Steinbeck’s 1962 Travels with Charley. On a Sunday morning in Vermont, Steinbeck decides to attend church, finds what appears to be a Presbyterian congregation, leaves Charley in his truck, and goes inside:

The service did my heart and I hope my soul some good. It had been long since I had heard such an approach. It is our practice now, at least in the large cities, to find from our psychiatric priesthood that our sins aren’t really sins at all but accidents that are set in motion by forces beyond our control. There was no such nonsense in this church. The minister, a man of iron with tool-steel eyes and a delivery like a pneumatic drill, opened with prayer and reassured us that we were a pretty sorry lot. And he was right. We didn’t amount to much to start with, and due to our own tawdry efforts we had been slipping ever since. Then, having softened us up, he went into a glorious sermon, a fire-and-brimstone sermon. Having proved that we, or perhaps only I, were no damn good, he painted with cool certainty what was likely to happen to us if we didn’t make some basic reorganizations for which he didn’t hold out much hope. He spoke of hell as an expert, not the mush-mush hell of these soft days, but a well-stoked, white-hot hell served by technicians of the first order. This reverend brought it to a point where we could understand it, a good hard coal fire, plenty of draft, and a squad of open-hearth devils who put their hearts into their work, and their work was me. I began to feel good all over. For some years now God has been a pal to us, practicing togetherness, and that causes the same emptiness a father does playing softball with his son. But this Vermont God cared enough about me to go to a lot of trouble kicking the hell out of me. He put my sins in a new perspective. Whereas they had been small and mean and nasty and best forgotten, this minister gave them some size and bloom and dignity. I hadn’t been thinking very well of myself for some years, but if my sins had some dimension there was some pride left. I wasn’t a naughty child but a first rate sinner, and I was going to catch it.

I felt so revived in spirit that I put five dollars in the plate, and afterward, in front of the church, shook hands warmly with the minister and as many of the congregation as I could. It gave me a lovely sense of evil-doing that lasted clear through till Tuesday. I even considered beating Charley to give him some satisfaction too, because Charley is only a little less sinful than I am. All across the country I went to church on Sundays, a different denomination each week, but nowhere did I find the quality of that Vermont preacher. He forged a religion designed to last, not predigested obsolescence.

I never knew Vermont used to be full of fire-breathing Presbyterians (or had any in 1960). It would be reassuring if it weren’t, in my best guess, a reflection of the semi-fictional nature of the book.

The problem of how to talk about sin is indeed vexing for many contemporary evangelicals. (It’s actually a rather easier affair for more liberal Protestants who talk more about communal and structural sin than individual morality.) Where’s the balance between what Steinbeck portrays and the hesitation now common in some churches? I don’t have an easy prescription, but I think it’s always best for any discussion of any sin to begin with 1 Timothy 1:15.