Not long ago, John Turner ignited controversy when he challenged the idea that Mormonism was a “cult,” a concept I have myself written on at some length. (By the way, some scholars define “cult” as “a small unpopular religion,” without specifying whether the unpopularity is merited).

For present purposes though, I am interested in another idea that surfaces repeatedly in these “cult” debates, namely that a particular movement violates “traditional Christian orthodoxy,” historic orthodoxy, or some similar term. This concept harks back to the criteria declared by St. Vincent of Lérins around 434, namely that the true faith is what has been believed always, everywhere and by all (quod ubique, quod semper, quod ab omnibus creditum est). The problem, though, is that this universal standard is very exacting. Just what tenets of faith might qualify as essential core doctrine?

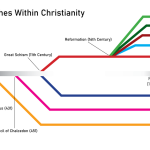

Sometimes, that orthodoxy is linked to the Council of Nicea in 325, which indeed established the idea of the Trinity. However, it also left theories of Incarnation fiercely debated until the Council of Chalcedon, in 451, and many ancient churches never accepted that decision. Yet not for a second would I dare say that the non-Chalcedonian churches – those heroic witnesses to faith under persecution – are somehow excluded from the Christian continuum. Meanwhile, Western Catholics and Eastern Orthodox both happily follow Chalcedon, but they disagree widely on the critical theory of the Atonement, with the West following ideas laid down by Anselm c.1100. In another highly sensitive area, Orthodox theologians are comfortable with the idea of theosis, literally “deification,” a concept that alarms many Western thinkers.

In other words, much of what Westerners – and especially Protestants – see as “traditional Christian orthodoxy” is not as universal or even as traditional as many assume. If we are talking about what Christians of diverse church traditions “always and everywhere” believed through the thousand years of the Middle Ages – that is, for a half of Christian history – then I suppose a deep veneration for the Virgin Mary should form part of that central orthodoxy. So should a firm belief in Eucharistic worship as the centerpiece of Christian life and devotion. Today, of course, most Protestants or Pentecostals do not share either of those tenets.

We easily find ourselves in something of a logic trap. Suppose that I assert that doctrine X is in fact within the bounds of orthodoxy, because it has been so widely accepted by various Christian groups across the centuries. Another person might fault my argument, simply because (in his view) anyone who believes such an outrageous thing is by definition not a Christian, and therefore their views cannot count towards the assessment of “always, everywhere and by all.” We soon find ourselves on the perilous sands of “I know it when I see it.”

That lack of consensus even applies to the definition of the Bible. Across the ecclesiastical spectrum, churches differ quite widely on whether they accept certain books as fully canonical, as apocryphal, or even reject them altogether. This diversity affects not just quirky modern-day sects, but also ancient churches rooted in many centuries of tradition, such as the Ethiopian. The Eastern Orthodox churches give canonical status to the Prayer of Manasseh, 3 Ezra, 3 Maccabees, and Psalm 151. Before the Reformation, even Western churches were open to what we today see as such oddities as the Epistle to the Laodiceans, or III Corinthians. On the other hand, many Eastern churches were dubious about some or all of the Catholic Epistles, and certainly of Revelation.

In fact, I do personally believe in an identifiable core of Christian orthodoxy, with a solid and indisputable scriptural core, which is found above all in the four canonical gospels. I am emphatically not saying that a church can wantonly and capriciously decide to alter its creeds – or its canon – and remain within that orthodox tradition. Nor is a church’s “Christian” status solely a matter of self-definition. Having said that, any historical perspective must show that the limits of acceptable Christian orthodoxy are much more expansive than many believe.