Material objects can evoke distant periods of history far more powerfully than even the greatest texts. Sometimes, they can also teach astonishing lessons.

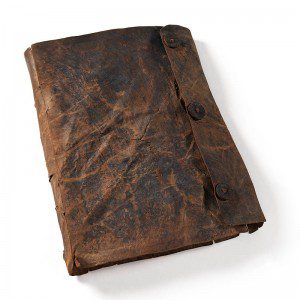

In the study of early and medieval Christianity, one of the most significant finds of modern times occurred in 2006, when peat diggers in Ireland’s County Tipperary uncovered a psalter from around the year 800, still in its original binding.

The psalter was a fundamental part of the worship of the Irish church, who divided the whole corpus of 150 psalms into the Three Fifties,” recited constantly. For Irish archaeologists, this Faddan More Psalter was the greatest single discovery since the legendary Ardagh Chalice turned up in 1868.

Although we can never know for certain, it is likely that the psalter was a treasured item that its owner hid in a time of threatened violence, presumably a Viking raid. The fact that it was not recovered means that the owner – a monk or nun? – perished or was enslaved, and never returned.

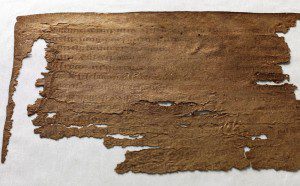

As an intact book from this era, the Faddan More Psalter is an amazing enough find in its own right. Even so, its story became even stranger in 2010, when archaeologists reported finding eighth century Egyptian papyrus in its cover. One remarks that “The cover could have had several lives before it ended up basically as a folder for the manuscript in the bog. … It could have traveled from a library somewhere in Egypt to the Holy Land or to Constantinople or Rome and then to Ireland.”

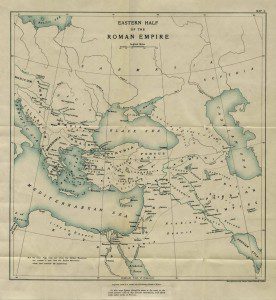

But the Ireland/Egypt connection is not necessarily a surprise. We have long known that the Irish church maintained strong links with the Mediterranean, and especially with those Eastern regions in which monasticism began. Just as Egyptian monks went off into the “desert”, so Irish and Welsh solitaries resorted to remote corners that are still today remembered through such place-names as Dysart or Dyserth.

Egyptian themes also appear regularly in the material culture of the Irish church, and of the English congregations that it influenced so powerfully. In an eye-opening piece some years ago, William Dalrymple discussed this “Egyptian Connection”: “One of the earliest known Insular gospel books, the Cuthbert Gospels, is bound and sewn in a specifically Coptic manner, which Michelle Brown believes indicates ‘an actual learning/teaching process’ linking Egypt and Northumbria. The same process is hinted at in the Book of Kells, which contains an image of the Virgin suckling the Christ child clearly taken from a Coptic original: the virgo lactans was a specifically Coptic piece of iconography borrowed from the pharaonic image of Isis suckling the infant Horus. The Irish wheel cross, the symbol of Celtic Christianity, has recently been shown to have been a Coptic invention, depicted on a Coptic burial pall of the fifth century, three centuries before the design first appears in Scotland and Ireland.”

As I have remarked elsewhere, “globalization” is by no means a new feature of Christian life!