Through the years, I have written a good deal about the globalization of Christianity in the modern world, but that interest springs naturally from much older interests of mine in transnational linkages in earlier eras. As I posted recently, the church of the early Middle Ages was thoroughly transcontinental, with all sorts of unsuspected linkages between very distant regions. Nothing could be further from the truth than to imagine Dark Age Christians skulking at home in their villages and local monasteries. In many cases, they knew a much wider world, and they were shaped by its influences.

Although it’s not specifically a Christian example, I always enjoy one piece of trivia, namely the coins of the eighth century English king Offa, a contemporary of Charlemagne. In the 770s, he decided to mint some rather splendid coins, which are among the oldest surviving examples of their kind in England. On the coin’s back, there is what the designer obviously thought was fancy decorative work on the original he copied from, which was an Arab dinar. And that is why the coin of this strictly Christian king bears the Islamic declaration of faith, in Kufic script! Multiculturalism long before its time…

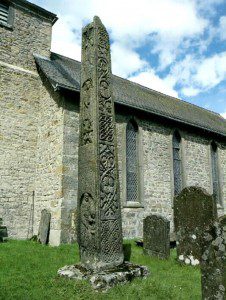

What matters here is that Middle Eastern goods were circulating even in the British Isles, and were avidly imitated by local craftsmen. (In France, Spain and Italy of course, such influences had far less distance to travel.) This helps us understand how literary and artistic Christian influences from distant Palestine, Syria or Egypt made their way to the far West, to manifest themselves mysteriously in manuscripts, paintings and carvings. We should not be surprised when we see very Mediterranean looking vine-scroll decoration on Anglo-Saxon stone crosses in remote corners of England or Scotland.

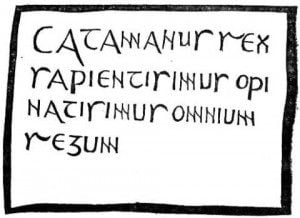

In my homeland of Wales, archaeologists have found plenty of traces of such Mediterranean links from the obscure years from around 400-650, when the country was already thoroughly Christianized. Several settlements have produced high-quality pottery from the Eastern Mediterranean, as well as Byzantine and Egyptian coins, while memorial inscriptions still continued to use the high-flown language of the Roman and Byzantine courts.

That Welsh context would be so important because of its strong influence on Ireland, and ultimately on the wider English and European churches.

Around the year 590, one Welsh chieftain decided to call his son Maurice, from the emperor then reigning in Byzantium, and as Meurig, the name became very popular throughout all ranks of Welsh society. Variously Anglicized as Morris, Merrick and Meyrick, it survives today as a common surname – although few people who bear it know that Dark Age/Byzantine link! Also around 600, other Welsh adopted the Byzantine name Theodore, Tewdwr, which eventually became Tudor. Others favored Eugenius – which became Owen.

And then there was Adomnán, the brilliant monk who headed the island monastery of Iona in the late seventh century. He wrote a hugely popular Life of St. Colmcille (Columba) Iona’s founder, and also (around 680) a superbly detailed and largely accurate account of the Holy Places in Palestine, De Locis Sanctis. You might ask an obvious question: how on earth did a monk living off the western coast of Scotland in the darkest of the Dark Ages happen to have the information that would allow him to write the book? Well, obviously, a passer-by had stopped off to tell him. Specifically, Adomnán was reporting what he had been told by a Gallic bishop named Arculf, who had visited Palestine, Egypt and Constantinople around 680, and was then shipwrecked at Iona on his return. Incidentally, not only did the Muslim occupiers not hinder Arculf’s tour, but he actually tells favorable stories about the Caliph, Mu’awiya.

Around 820, the Irish scholar Dicuil gave a good description of the Pyramids based on what he had been told by a group of Irish monks who had seen them as they were sailing up the Nile. The monks had stopped off to measure these marvels, which they did quite accurately. (They thought they had visited the granaries that Joseph had built for Pharaoh many centuries before). Suggesting the wide range of the world known to Irish Christians, Dicuil also reports other monks who had apparently visited Iceland, long before its official “discovery” by the Norse.

When we look at the medieval church, it’s often hard to appreciate the connections with the older Christian world of the Mediterranean, the world of the Roman and Byzantine empires. In fact, though, the linkages between old and new churches were much stronger and more direct than we might imagine.

In the furthest West, Christians never forgot they were part of a world rooted in Jerusalem.