This column is about one of the truly great Christians of Late Antiquity, but someone you will probably not have heard of. In a world falling into ruins, he kept faith and learning alive. His name was Illtud – and finding him demands a little detective work.

You have to be really famous for people not to mention you by name. Suppose for instance I was discussing religion in 1950s America, and I talked about “that great evangelist, with all his revivals and crusades, the man who prayed with presidents,” but without giving a name. It’s a reasonable assumption that I mean Billy Graham, but the fact that I expect you to know that means that I must be dealing with a household name.

Let’s go back now to Britain in the sixth century, a time of extraordinary violence and social collapse. One of the very few writers whose words survive was Gildas, who around 540 denounced the kings of his day. A special target of his wrath was the powerful Maglocunus, of North Wales. At one point, Gildas says he should have no need to warn the king, who had “had as instructor the refined teacher of almost the whole of Britain” (cum habueris praeceptorem paene totius britanniae magistrum elegantem). Presumably through this early influence, Maglocunus himself in later life had taken up the monastic life, although he had soon reverted to his brutal secular ways. Gildas does not need to name this legendary teacher, this magister. Maglocunus would know it and so, more important, would all Gildas’s readers. How many “teachers of almost the whole of Britain” could there be? Why spell it out?

Who, around 500, might have enjoyed this kind of fame? In one sense, we have too many possible answers. Lots of later medieval saints’ lives described spiritual heroes living around that time, and claimed that every king and scholar beat a path to their door – but we don’t have to believe anything written five hundred years after the event.

But one near-contemporary text does describe such a “teacher” at just the right time and place. One great saint of the early sixth century was Samson, who settled at Dol in Brittany until his death around 565. Samson’s nephew wrote a biography, which was later adapted about 610. That gives us a good link to the real Samson, who was born to aristocratic parents in south Wales about 486: both his parents’ families served the royal courts of local kingdoms. At the age of five, Samson was sent to study under the great teacher Eltutus, whom the Life praises to the skies as “of all the Britons the most accomplished in all the Scriptures, the Old and New Testaments, and in learning of every kind, of geometry, rhetoric, grammar and of all the theories of philosophy.”

Now, this makes great sense. Through the Middle Ages, one of the most celebrated Welsh saints was Illtud, whose name in Latin form was Eltutus or Iltutus. Although his medieval Life is late and dubious in its historical quality (he’s allegedly a cousin of King Arthur), there is no doubt that we are dealing here with a very influential figure of the fifth/sixth centuries. He is also frequently cited in saints’ lives as their teacher or mentor. Illtud is by far the best candidate for Gildas’s magister – indeed, really the only plausible claimant.

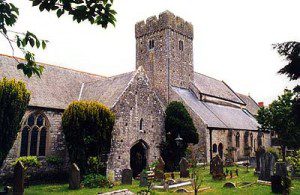

His famous monastery was at Llanilltud Fawr, “Illtud’s Great Church,” which survives today as the lovely village of Llantwit Major in South Wales. The village stands in the Vale of Glamorgan, a wealthy and fertile territory with abundant evidence of Roman occupation, with its road system and villas, and a powerful fortress nearby at Cardiff.

Llantwit Major itself had a villa, although there is as yet no direct evidence of a link with the medieval monastery. In the ninth century, another local “Samson” raised a memorial stone here to a number of local saints, including of course “ILTET.”

Documentary evidence in land charters shows that at least from the sixth century, the region was still divided into basically old-style Roman estates, which operated under something like Roman land law. In the fifth century, Iltutus would presumably have lived and worked in a highly Roman environment. It’s a fair assumption that he would have been a member of the local landed elite, who turned his old secular property into a monastery. Such examples are well known in contemporary France and Italy. Incidentally, we appear to have at least two similar cases quite nearby in the Vale of Glamorgan itself, at Llancarfan and Llandough, where the line of descent from older Roman buildings into monasteries is clear.

What makes Illtud’s story somewhat different is its traditional Celtic quality. Curiously, the Life of Samson adds that Illtud’s family was already celebrated for prophecy and knowledge of the future, and he was born a magician. Seriously, are we dealing here with a descendant of druids, as well as Roman landowners?

Assume that Illtud was born around 450, and created a monastery with a thriving school. I have already suggested that it’s in the mid-late fifth century that monasticism makes its first major impact on the British church, and thereafter the movement grew rapidly. Llanilltud became so famous that it attracted royal and aristocratic families from across Wales, and further afield – “almost the whole of Britain,” in fact. He taught kings. Gildas himself was probably another pupil, and his words to Maglocunus sound as if he is harking back to a shared experience under the same teacher. Several other Breton saints claimed Illtud as their teacher. Through those leaders – and through Samson and Gildas – the influence of the Llanilltud monastery-school permeated the emerging church in western and northern Britain, in Wales, in Brittany and western Gaul, and (most important for the long term) in Ireland.

Illtud surely deserves the title of the spiritual godfather of the emerging Celtic church.

But let’s look again at those dates. Illtud’s career would have reached its height between perhaps 480 and 520, a time of catastrophe in much of Britain. At least in southern and eastern England, the old Roman order had collapsed utterly, the cities were falling into ruins, and the ecclesiastical structure was evaporating. The Latin language was close to extinct, and the British Celtic tongue survived among slaves and the underclass. British/Welsh culture flourished in northern and western Britain, among the new warlord society, who maintained some Roman names and pretensions – but precious little survives of any intellectual endeavors.

And at this worst of times, Illtud kept alive the Christian faith and Roman education of an older more “elegant” world. It’s an astonishing achievement.

It also makes us think of a European near-contemporary who similarly tried to formulate a new Christian civilization amidst a falling world. I mean St. Benedict of Nursia (480-547), who is no less than the patron saint of Europe. The two men, Benedict and Illtud, had so much in common. When we commemorate the one, we really should remember his British contemporary.