God reveals Godself…

My ears pricked up during a recent sermon at a local Presbyterian church. I’ve heard “Godself” used by mainline ministers with some regularity since I went to seminary some dozen years ago, but I’m not used to it.

I’ve long been fascinated by the liberal Protestant quest to neuter God. I sat among students in seminary who would render male Greek words into gender-neutral alternatives. In my mind, this simply led to mistranslation, because the language of scripture is patriarchal. May as well translate it properly, and then think about how to use it in liturgy and preaching.

Liberal Protestants make, in my view, a good argument that male language for God sacralizes patriarchy. If human beings think of God as male, it lends a certain amount of credence to patriarchal structures of human relations. This is probably true even if Christians add disclaimers that male language about God does not mean that God is male. Thus, by this logic, it is good that Christians have been seeking ways to rhetorically distance themselves from patriarchy.

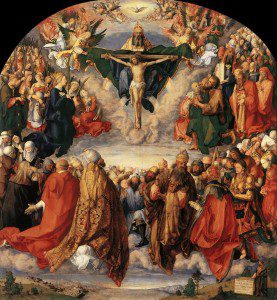

I’ve just finished reading Ed Blum and Paul Harvey’s The Color of Christ, an account of how Americans have imagined Jesus’s appearance since the seventeenth century. Toward the end of the book, Blum and Harvey note that most evangelical churches have removed pictures of Jesus from their sanctuary because of the inevitable problems raised by choosing a skin color for Jesus. Churches no longer wanted to sacralize whiteness by hanging pictures of a white Jesus, and there wasn’t an easy substitute. Similarly, churches should want to take steps to avoid sacralizing patriarchy by using rhetoric that presents a male God. However, one simply cannot banish male language for God. One needs substitute words and phrases.

Easier said than done, of course. Mainline Protestant language about God and human beings has changed dramatically over the past several decades. New hymnals (the Presbyterians are bringing out a new hymnal this year, replacing what I still think of as the “new hymnal” which replaced the “red hymnal” of my youth) edit out male language for human beings and decrease the use of male language for God. In the 1968 hymn “They’ll Know We Are Christians by Our Love,” the new hymnal changes “we’ll guard each man’s dignity / And save each man’s pride” to “we’ll guard human dignity and save human pride.” Such changes seem pretty reasonable. I now regularly use “humankind” in my own rhetoric rather than “mankind.”

It’s a much harder task for Christians to revise the final verse of that hymn: “All praise to the Father / From whom all things come / And all praise to Christ Jesus His only son / And all praise to the Spirit / Who makes us one.” Father language for the first member of the Trinity is nearly inescapable for Christians because of the language that Jesus used. Switching from “God the Father” to “God the Creator” does not work for Christians because of our belief in the role of God’s Word in creation. Nor can Christians easily discard the title of “Lord” for both the Father and Son. Tricky stuff, human language.

When sitting in church recently, I started wondering when ministers began using the term “Godself.” It seemed, at best, uncommon prior to 1980. I found an interesting article in the June 9, 1980 issue of Christianity and Crisis, penned by James F. White (then a professor at Southern Methodist University’s Perkins School of Theology) about liturgical renewal. White had this to say about “Godself” and related terms:

The only serious problem in this area is the reflexive pronoun. In my own writing, I have come to use regularly “Godself,” which after one year of use becomes perfectly normal. But in liturgical texts we simply avoid the reflexive. There is some loss since pronouns can make a text more personal. Any attempt to balance “he” with “she” makes the reference highly confusing to the worshiper. So we have decided to avoid third-person pronouns except for Jesus Christ.

It occurs to me that even should Christian liturgists follow White’s advice, they will still be sacralizing the maleness of God because of Jesus, so strictly speaking, it’s only a partial solution. White’s point, however, is good. If one finds male pronouns for God offensive, one should not use pronouns and should certainly not use the reflexive pronoun. Time to get creative.

Regardless, though, I can’t get used to “Godself.” It doesn’t seem “perfectly normal” to me. It seems so abstract and impersonal. And yes, a personal and intimate Jesus might make up for a distant and abstract God, and to some extent, American Christians could stand to be a bit less chummy with God. Still, when I read the Bible, I read about at least moments in which God draws very close to human beings, speaks to them, cultivates a loving if sometimes perplexing relationship with them. In my mind, there is a danger in making God an impersonal abstraction. “For God so loved the world that God gave God’s only begotten son…” just doesn’t quite work.

Some Christians turn these struggles over language into battles that permit no compromise, either never using any language for God or fighting every reasonable change (and loudly singing out the “old” words to favorite hymns). This seems a violation of Christian charity. One of my seminary professors in his translations of the Psalms substituted “Who” for “He Who” at the beginning of many lines. It in no way diminished the eloquence of the text. Another of my seminary mentors made a point of using a male pronoun for God exactly one time in the course of her presbytery sermon.

One lesson from the Hebrew scriptures is that human language is necessarily confused and corrupt. We do not speak the pure language of heaven. We have to do the best we can within our limitations. This, of course, is just my view from the pew, not a serious attempt to grapple with matters of language and justice.