Who’s the odd man out: Ambrose, Patrick, John Chrysostom, Leo the Great, Shenoute?

All were great Christian leaders who lived in the century after 350. But it’s a trick question, as there are two answers. One answer is “Patrick” as we have virtually nothing written by him, while the others all left copious literary remains. Alternatively, we should say “Shenoute,” as he’s the only one whose name is unknown to the vast majority of educated Christians, even those with long experience in church history. As I’ll argue, the amnesia about Shenoute is truly sad. It is also a powerful object lesson in the making and breaking of historical reputations.

Shenoute reputedly lived from 347 to 465, and revolutionized the practice of monasticism in Egypt. By the time of his death, his White Monastery was home to several thousand monks and nuns (Its remains stand near Sohag). He also had a powerful impact on the political world, and attended the Council of Ephesus in 431. He wrote at astonishing length.

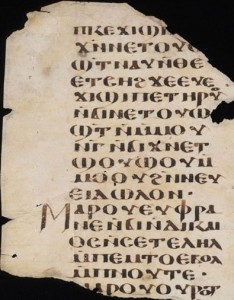

Shenoute’s writing is at once the core of his greatness, and the reason for his obscurity in the West. He wrote in Coptic, which over the previous two centuries had become a standard language for Egyptian Christianity. All key Christian texts were translated into Coptic, and Christians composed many new works. St. Anthony, founder of monasticism, was a pioneer of that tradition, and he also gives some idea of the language’s spread. Already by the end of the third century, the non-Greek speaking Anthony was hearing the Bible in church, either from a Coptic manuscript or an oral recitation. When the Nag Hammadi library was discovered, the books were of course in Coptic.

Shenoute himself was an amazingly prolific writer. Some four thousand pages of his writings survive around the world. He did not despise Greek, or view it as a language of alien occupation, but as a monk from Upper Egypt, Coptic was his natural medium. He wrote work of extremely high quality and sophistication.

It is difficult to overestimate his importance to that Coptic tradition. He was “the first outstanding writer of the Egyptian language in its Coptic form, and his literary importance was never equaled.” His disciples and successors strove to carry on as he had begun. Through those efforts, Coptic greatly increased its prestige as a language of literature and scholarship

This linguistic fact is enormously important for the survival of Christianity in Egypt. After the Islamic conquest of the Middle East, the pressure to join the more dominant religion was obviously strong. Egyptians, though, were very slow to abandon a religion that was so wholeheartedly acclimatized in their soil, and which spoke their native language.

That is why, even in the twentieth century, some ten or fifteen percent of Egyptians were still Christians, proud members of the Coptic Church. In very recent times, that church was headed by its Pope Shenouda III, who reigned from 1971 through 2012. His name is a variant spelling of Shenoute. (You can now see a reverential documentary about the modern-day Pope Shenouda).

But that Coptic tradition of course is the problem with the historical reputation of the original Shenoute. After the fifth century, theological debates drove a wedge between the Coptic and Greek-speaking worlds. Even those Catholic or Orthodox churches who remained aware of Egypt maintained their distance from the Coptic Church, which they regarded as Monophysite. The Islamic Conquest further reduced links with Europe, which increasingly became the demographic heart of the Christian world. Even after the Renaissance, the Coptic language was unknown in Europe except to a handful of highly trained specialists.

Not until the twentieth century did some visionary scholars realize what a knowledge of Coptic might contribute to understanding early Christian history, a message reinforced by the Nag Hammadi finds. In recent years, scholars have produced several key studies on Shenoute and his world, including Rebecca Krawiec, Shenoute and the Women of the White Monastery: Egyptian Monasticism in Late Antiquity; Caroline T. Schroeder, Monastic Bodies: Discipline and Salvation in Shenoute of Atripe; and most recently, Ariel G. Lopez, Shenoute of Atripe and the Uses of Poverty: Rural Patronage, Religious Conflict, and Monasticism in Late Antique Egypt. Stephen Emmel has edited Shenoute’s Literary Corpus (Leuven: Peeters, 2004).

Even so, it is striking that so much of Shenoute’s work remains untranslated. This is doubly startling for scholars of early Christianity or Judaism, who can easily refer to Internet sources for translations of even the more obscure ancient texts, by writers far less significant that Shenoute. Can we imagine a world in which the works of (say) Augustine or John Chrysostom remained untranslated and unavailable to non-specialists?

In the fifth century, any reasonable survey of the Christian world would have rated Shenoute’s importance astronomically high, in marked contrast to a distant border evangelist like Patrick. The comparative history of the two reputations is a humbling statement about how historical reputations are shaped by events occurring long after the lifetime of a particular individual.