Once upon a time, the Alexandrian Patriarch Mark was visiting a provincial Egyptian city called Agharwah (Aghra). “And the clergy came out to meet him according to the custom, that they might chant before him, with a body of the laity, chief men and leaders of the people; and he blessed them and prayed for all of them. And there came out among the others a person possessed by a devil, which threw him down in the midst of the people, and choked him until foam flowed from his mouth.” The Patriarch then made the sign of the Cross over the man’s face, so that he was healed. “So that man threw himself at Abba Mark’s holy feet, and thanked God for the deliverance thus granted.” The Patriarch admonished him to be careful in taking Communion in future, lest the possession be repeated.

Nothing in that story seems surprising for anyone familiar with the Christianity of Late Antiquity or the early Middle Ages. What is notable, though, is the date, as the episode occurred around 810, when Egypt had been under Muslim rule for 170 years. Yet reading an account like this, so little seems to have changed. Monks and bishops still go about their lives in a heavily Christian countryside, with the usual roster of apparitions and miracle stories. It casts a different and often surprising light on popular impressions of the Muslim conquest of the Middle East.

The source is an amazing and very substantial document called the History of the Patriarchs of the Coptic Church of Alexandria, which is available online full text, running to some 175,000 words in translation. Some two-thirds of the narrative takes place after the rise of Islam.

With such a lengthy source, it would be easy to cherrypick, to select incidents that confirm one interpretation or another. You want to show that Christians had few problems with the Muslim occupation? You want to show that the Muslims were ruthless persecutors? The History offers rich pickings for either approach. The answer, of course, lies somewhere between, and a nuanced reading is essential.

From the anti-Muslim perspective, you might for instance choose this story from 718. Muslim authorities

commanded the monks not to make monks of those who came to them. Then he mutilated the monks, and branded each one of them on his left hand, with a branding iron in the form of a ring, that he might be known; adding the name of his church and his monastery, without a cross, and with the date according to the era of Islam. … If they discovered a fugitive or one that had not been marked, they brought him to the Amir, who ordered that one of his limbs should be cut off, so that he was lame for life.

However, this extraordinary situation soon passed, and the History records the relief that later caliphs granted to Christians, in Syria as well as Egypt:

after him reigned Hishâm his brother, who was a God-fearing man according to the method of Islam, and loved all men; and he became the deliverer of the orthodox. For when he learnt that we Christians had had no patriarch in the East since Julian, the late patriarch of Antioch, in whose stead the bishop Elias had taken his seat, and that Elias also had died, he took a man named Athanasius, full of every spiritual grace, who also was a bishop, and gave him the patriarchate of Antioch. So the bishops laid their hands upon him in turn, and made him patriarch.

Some Muslim rulers were wise and benevolent, others were ruthless thugs. It sounds very much like the secular regimes that saints were confronting in contemporary Christian Europe, although the Muslim rulers were marginally less nervous about committing sacrilegious acts that could draw down divine anger. Often, when the History describes a brutal tyrant, it mentions that he was a terror to all the subjects, Muslim as well as Christian. Often, not always, this was equal opportunity tyranny.

Oddly too, the church historian regards even the worst atrocities visited on Christians by Muslims as fairly minor compared to those inflicted by other Christians in past times. From the fifth through the seventh centuries, Egypt had usually been under the rule of Orthodox Chalcedonian Roman regimes, who were determined to enforce their will on the overwhelmingly Miaphysite Coptic Christians. Large sections of the History are devoted to the tortures, martyrdoms and persecutions involved in that process, after which the Muslims came almost as a relief.

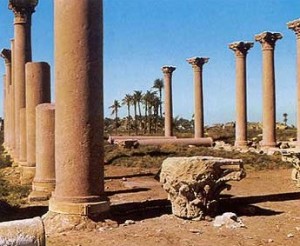

What makes the History so striking is its combination of worlds that we often think of as so radically separate, the medieval Christian and the “Oriental” Muslim. This is nowhere brought home more effectively than in the name of the work’s tenth century compiler, the Bishop Severus, known as Severus ibn al-Muqaffaʿ, or (from his diocese) Severus of El Ashmunein. El Ashmunein is the name given to the ancient Egyptian and Hellenistic city otherwise known as Khmun, and later as Hermopolis Magna. Roman, Greek and Arabic names merge together, very much as the cultures did in the Egypt of his time.

Severus certainly saw signs of trouble in his day, the late tenth century, when the Coptic language was fading before the spread of Arabic. He even made grudging concessions to this process, by publishing works in Arabic himself. But even three centuries after the coming of Islam, he gives little impression of serving a church in danger of vanishing.

I am painfully well aware of the plight of the church in modern-day Egypt, especially given the savage violence and mob attacks directed against Christians just in the past few days. But it wasn’t always thus.