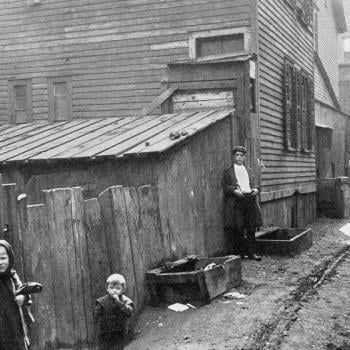

In recent years scholars have accentuated the individualistic impulse within conservative evangelicalism. Evangelicals, Christian Smith and Michael Emerson pointed out in Divided By Faith, often understand racism as a long series of personal white-on-black abuses more than a practice built into economic, social, and cultural systems. Typically this impulse is contrasted with secular liberal attention to structural inequalities. This formulation has much utility, for evangelicals have retained a passion for individual souls and bodies. They see micro-enterprise programs as desirable because they maintain long-term relationships with local communities in the two-thirds world. The Farmer-to-Farmer program, which pairs farmers from Iowa with farmers in Nicaragua, embodies this strategy, as does World Vision’s support of over 440,000 projects in 46 two-thirds world countries.

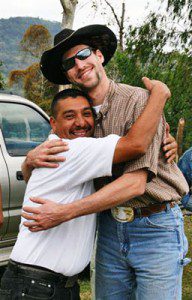

According to these new evangelical internationalists, impersonal campaigns and technocratic methods of addressing injustice are humanized and made better when they attend to particular communities. One southern megachurch pastor explained, “We do not tell a community that we know what their problems are and how to fix them. We try to find out what the perspective of the community is, and we often learn more than they do.” Shane Claiborne, for instance, a “New Monastic” who is very attentive to structural sources of injustice, speaks ardently about “when people fall in love with each other across class lines.” Evangelicals are consistently driven, as if “by gravitational force,” according to Omri Elisha, toward direct influence, relationships, and personal purity. Even if the global pandemic of sex trafficking can’t be stopped through the sanctification of men’s lustful minds, those minds still need to be purified.

But this formulation has limits, according to growing numbers of evangelicals. They increasingly seek national and global structural change in their policy prescriptions. The World Evangelical Alliance, for example, has launched a campaign called the Micah Challenge that addresses education, poverty, hunger, gender equality, maternal health, HIV and other diseases, environmental sustainability, and economic development—and places them in the context of human rights and shared responsibility for the condition of all peoples. Advocates urge pursuit of the Millennium Development Goals devised by the United Nations in 2000. The Micah Challenge represents the significant activity of younger evangelicals in starting institutions, lobbying Washington and other global capitals, and launching media campaigns. They are often very articulate in describing the structural patterns of inequality that lead to poverty, human trafficking, and human rights violations. These attempts at global development problematize the binary that ties individualist logic to conservatism and structural logic to progressivism.

Numerous other examples also confound the binary. Secular and religious progressives, for example, violate the old model by continuing to use hero myths and individual agency to assert themselves in the public sphere. On the other end of the spectrum, the anti-environmentalist Cornwall Alliance now frames many of its arguments in terms of social justice. This organization has begun to argue that environmentalism is a threat to prosperity and freedom—that it hurts the poor and that the cost of curtailing climate change will undermine the economic system. Similarly, structural language can now be found among conservatives in the Heritage Foundation. Most significantly, a rising group of “new evangelicals,” as Marcia Pally calls them, have come to consensus around a “mix of market and common good.” She writes that this cohort upholds “individual initiative and entrepreneurialism in markets, but this does not commit them to just any market action but rather to those that follow an ethics of resource-distribution and opportunity-restructuring for the flourishing of all.” The National Association of Evangelicals’ 2001 statement “For the Health of the Nation” supports not only a free-market system and private property, but also startling structural language having to do with religious freedom, family life and the protection of children, sanctity of life, caring for the poor and vulnerable, human rights, peacemaking, and caring for creation.

Numerous other examples also confound the binary. Secular and religious progressives, for example, violate the old model by continuing to use hero myths and individual agency to assert themselves in the public sphere. On the other end of the spectrum, the anti-environmentalist Cornwall Alliance now frames many of its arguments in terms of social justice. This organization has begun to argue that environmentalism is a threat to prosperity and freedom—that it hurts the poor and that the cost of curtailing climate change will undermine the economic system. Similarly, structural language can now be found among conservatives in the Heritage Foundation. Most significantly, a rising group of “new evangelicals,” as Marcia Pally calls them, have come to consensus around a “mix of market and common good.” She writes that this cohort upholds “individual initiative and entrepreneurialism in markets, but this does not commit them to just any market action but rather to those that follow an ethics of resource-distribution and opportunity-restructuring for the flourishing of all.” The National Association of Evangelicals’ 2001 statement “For the Health of the Nation” supports not only a free-market system and private property, but also startling structural language having to do with religious freedom, family life and the protection of children, sanctity of life, caring for the poor and vulnerable, human rights, peacemaking, and caring for creation.

The old individualist-structuralist categories are becoming more complicated.