In the mid-twentieth century the world underwent geopolitical reorientation. Decolonization carved the imperial-colonial divide into a new landscape, and World War II left only two major superpowers: the Marxist Soviet Union and the liberal democratic United States. Once allies against Nazi Germany, ideological differences rapidly turned them into foes.

Each side began to “recruit” allies around the world in order to fight by proxy. Some of the warfare consisted of “soft diplomacy” (here’s an example called “American Imperialist: The Millionaire” from the Soviet Union and a comical Wendy’s commercial from the U.S. called “Soviet Fashion Show“). The Soviets, offering “friendship treaties,” corralled Poland, Cuba, Korea, Vietnam, and Syria into the Warsaw Pact. They offered military advice, trade credits, support for national liberation–and sometimes outright military aggression. For their part, the Americans and Western European nations allied with Israel, West Germany, and Egypt, organizing under umbrella coalitions like NATO and SEATO and using economic aid as bait. To counter Soviet influence, the U.S. assassinated an Iranian leader and installed a puppet government. For dozens of newly independent states, independence never actually arrived as the United States and the Soviet Union carved up the world between them.

Several tentative efforts were made to organize newly independent, non-aligned states. These nations would oppose both US and USSR influence. But the Cold War exerted powerful pressures, and the efforts did not work.

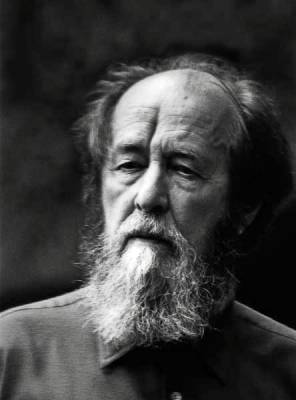

How did non-Western evangelicals fit into this landscape? Courted and caught between Marxist and capitalist imperialisms in an era of decolonization, many non-American Christians felt beholden to neither. On one hand, most denounced Marxist totalitarianism. For example, Alexandr Solzhenitsyn, author of Gulag Archipelago and One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, memoirs that chronicled horrifying atrocities, condemned the Kremlin. But Solzhenitsyn, with a full beard that summoned visions of the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah, also leveled his prophetic ire toward the West. In his 1978 commencement address at Harvard, he decried “all this freedom with no purpose” but for the “satisfaction of one’s whims.” “Destructive and irresponsible freedom has been granted boundless space. Society has turned out to have scarce defense against the abyss of human decadence,” he declared. Western culture, defined and driven by relentless capitalism, was defined by “the revolting invasion of commercial advertising, by TV stupor, and by intolerable music.” America, he suggested, had lost its soul. Even worse, the West was exporting its obsession with capitalistic materialism. In the 1990s Solzhenitsyn accused the West of imperialistic designs on Serbia, Ukraine, and Iraq.

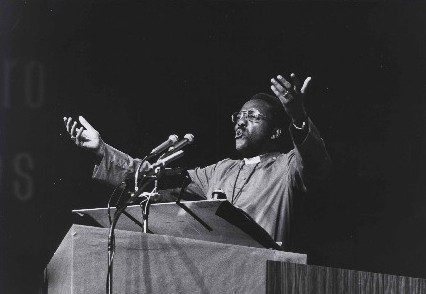

Many evangelicals from the two-thirds world amplified Solzhenitsyn’s critiques of both Marxism and capitalism. Each, they said, hindered human flourishing. Few liked the totalitarian versions of Marxism in Russia and China. Festo Kivengere, a Ugandan bishop known as the “Billy Graham of Africa,” said, “In Marxism … man is useful for the state and is thrown away when no longer useful. In capitalism, persons are useful as they bring profit to the company or to the society and are put on the shelf when they are no longer profitable.” American commitment to unfettered capitalism, others suggested, impeded attention to social justice.

International evangelicals were particularly sensitive to American alliances with anticommunist nations guilty of human rights abuses. Andrew Kirk, a long-time missionary in South America, wrote, “Evangelicals have a bad track-record in questioning traditions handed down to them. … On a number of occasions, for example, I have heard evangelical Christians defend right-wing, totalitarian governments (like those of South Africa or Paraguay) on the grounds that they allow complete freedom to preach the gospel.” Sadly, Kirk concluded, “the gospel that some proclaim is indeed ‘good news’ to oppressive regimes, for, while speaking of an ‘inner’ freedom that transcends life in this world, it does not in any way challenge policies that have resulted in the severe loss of civic freedoms for vast sections of the nation.” Kirk and Kivengere represented many international evangelicals unwilling to bend to Cold War categories.