I was hugely grateful for Tommy Kidd’s recent column on publishing in history. His post took so many themes that are quite familiar to academics and professional scholars, and then unpacked them for non-specialists in an extraordinarily valuable way. That was a real contribution.

Like Tommy, I also lay claim to being a prolific publisher. (If he carries on as he is, he will undoubtedly surpass me before too long, the whippersnapper). I’m sometimes asked if I have any advice for writing generally. I don’t have any cosmic secrets to offer, but the following thoughts might be of some use. If they work for you, that’s wonderful. If not, then that’s fine also. Use what works for you.

Incidentally, much of what follows also applies strongly to writing dissertations!

In no particular order:

*Nobody ever wrote a book. People write chapters, which are brought together to form a book.

These often begin as articles or individual studies. In most cases, authors begin with an overall vision of a larger project, but not always – they just write individual studies, and only gradually see possible connections. What they are doing, in fact, is groping their way to seeing the overall grand theme, around which to frame the book. In some instances, authors put six or so of those discrete components together, create links between them, and then make the chapters speak to each other. As the process develops, those links themselves merge to define the main thrust or argument of the work, with the individual chapters providing a supportive framework. And the author has a book.

But even if the author begins with a grand scheme or design, such as a biography, s/he still has to divide it up into workable, manageable units, and the point about links is just as valid.

Think of building a bridge. You absolutely have to start by building the pillars of the bridge. Once they are solid, then you reach out to link between those pillars, and that is how the bridge emerges. Once the whole thing is complete, all the attention goes to the bridge span, not the pillars, but you need both. The bridge is the book, the pillars are chapters. No sane person ever began by building a bridge span, and then as an afterthought paid attention to the pillars or supports that might hold it up.

Think centrally throughout about constructing those individual components, rather than setting off to write THE BOOK as a whole.

*”What is this book about?” “This book is about 240 pages.”

That may sound like a joke, but it actually makes an important point. Especially when starting off their careers, people feel the need to cram everything they know into a book. It’s far better to say what you have to say in a limited space, and then save the remaining material for your next book, or the one after that. Decide what you have to say, say it, stop, and move on.

Of course, it doesn’t always have to be 240 pages – 140 or 340 can both be fine, as appropriate. I’m not necessarily recommending writing short books, rather that you define a limit, and don’t go far over it! This forces you to make tough (and essential) decisions about what can or cannot be included in the particular text.

Each of my last dozen or so books has grown out of an idea in a short section or paragraph in one of the previous books. I can almost map it like a flow chart.

*On a related point, think carefully about the units making up the book, assign each a length, and stick to it.

Does that sound obvious? I learned the lesson the hard way. I remember many years ago writing a book on the History of Wales, which had about fifteen chapters, and which needed to be some 400 pages in all. Do the math. In other words, each chapter needed to be about 25 pages, no more than 8,000 words in all. I had one chapter on industrialization, with a major section on coal. By definition, that coal section could not have been vastly more than 4,000 or 6,000 words. And then I found myself some 15,000 words into the coal industry section, with no end in sight!

The moral: first determine the overall length of the book, then do a chapter list, figure out what your chapters and sections are, and what materials fit into each chapter. You might for instance determine that each chapter should be 25 pages, and in that space you will address five or six specific topics or subheadings. Without too much access to higher mathematics, you then know that each of those topics must be covered in about four or five pages – which really is not much. So lo and behold, you then know how much space you can devote to each topic!

If you then find yourself writing page 75 of that 25 page chapter, the time has come (duh!) to stop and rethink. Might you in fact be writing another, second, book?

That process, of shaping the chapter outline, is by far the most important stage in the design and construction of a book.

*Again this sounds obvious, but think carefully about the audience you are aiming at, and never forget that target audience. While I try to be strictly respectable in academic terms, for instance in fully citing my sources, I also try to aim for a large non-specialist, non-academic audience. Most basically, that means choosing an appropriate level of vocabulary. It also means thinking very hard about what the average intelligent non-specialist reader might be expected to know, and what will need explanation.

In this process, I have found it immensely useful to do various kinds of journalism and popular writing, op-eds and magazine articles, or blogs like the Anxious Bench. Such work contributes greatly to fluency and speed, and to writing at a level that works for a general audience.

* I offer a caveat there. The most valuable commodity you possess is time, so decide how to use it most efficiently. If you aim to write a major project, such as a book, be very careful about assessing the possible gains and losses from other projects that might arise along the way, such as writing book reviews, columns, or (yes!) blogging. As I suggested, these might be extremely valuable in helping you learn to write well, or drawing attention to your work. They might also be lucrative. But if they take too much from your main time, or if they become an end in themselves, learn to say no.

*Following on from the issue of audience, it’s also vital to think carefully about presses, and how they are going to market what you write. Why, after all, are you writing something in the first place? Presumably, to reach the largest possible number of people. Often, high prestige academic presses do a rather poor job in marketing and publicity so that work is effectively wasted. Look carefully at what presses have done in the past, and make your judgment accordingly.

As a general rule, when trying to place a book, always begin with publishers at the top of the tree, even if that means aiming unrealistically high.

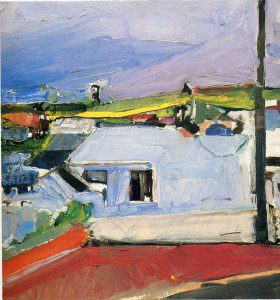

*Finally, you can make what you like of this point. I am a great fan of the painter Richard Diebenkorn. When he died in 1993, the following document was found in his papers. I think it is quite brilliant as a guide to the creative process, applying as thoroughly to books as to visual arts. But don’t press me on the exact meaning of any specific statement!

NOTES TO MYSELF ON BEGINNING A PAINTING

- Attempt what is not certain. Certainty may or may not come later. It may then be a valuable delusion.

- The pretty, initial position which falls short of completeness is not to be valued — except as a stimulus for further moves.

- Do search. But in order to find other than what is searched for.

- Use and respond to the initial fresh qualities but consider them absolutely expendable.

- Don’t “discover” a subject — of any kind.

- Somehow don’t be bored — but if you must, use it in action. Use its destructive potential.

- Mistakes can’t be erased but they move you from your present position.

- Keep thinking about Polyanna.

- Tolerate chaos.

- Be careful only in a perverse way.