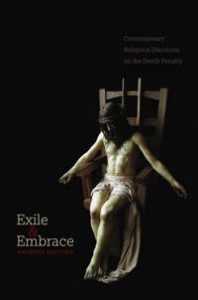

Anthony Santoro’s Exile and Embrace: Contemporary Religious Discourse on the Death Penalty features one of the more arresting book covers I’ve seen in recent years. A pierced and bloody Jesus sits in an electric chair, wearing a crown of thorns and a waistcloth.

The photo is of a wax sculpture by Paul Fryer, who offers this explanation:

Just as the cross was the preferred method of execution in the Roman Empire at the time of Christ, the electric chair was the prevalent method in 20th-century America. If the technology had existed then He would probably have been electrocuted. Had that been the case, millions of people around the world would now be wearing miniature gold and silver electric chairs on chains around their necks.

Santoro’s book is timely. Although solid majorities of Americans continue to support capital punishment, its future seems more fragile than it did two decades ago. Slowly, “abolitionists” have gained some ground in recent years, eliminating the death penalty in states such as New York and Maryland. Even so, Santoro (who is a colleague of mine this year) observes that in 2010 the United States “ranked fifth in number of known executions, behind China, Iran, North Korea, and Yemen.”

Santoro’s focus on religion is also welcome. Historians and other scholars have written a great deal about how various religious groups have responded to issues such as homosexuality and feminism (and some work about evangelical prison ministries), but there are relatively few studies about how American churches or their members have engaged the subject of capital punishment. Nevertheless, Christians have long taken active stances on both sides of the issue. Santoro notes that in nineteenth-century debates over capital punishment (a number of states abolished the death penalty around the middle of the 1800s), the “most prominent partisans on each side … tended to be clergy.”

I find Santoro’s book praiseworthy on two accounts. First, he focuses on Virginia, likely to become a battleground on the issue. Santoro includes a detailed description of Virginia’s death row (in the summer “a combination sensory deprivation chamber and oven,” according to one observer), and he introduces victims, murderers, and their respective advocates.

Santoro also casts a broad net in terms of religious data, discussing Catholics, evangelicals, and liberal Protestants. Needless to say, Christians in Virginia, like those elsewhere in the country, disagree vigorously about capital punishment. Santoro writes, “These differences essentially break down to two related questions: How is the Bible to be read and understood, and what is the relationship between the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth and those contained in the Old Testament?” Santoro did field work at Virginia churches, attending Bible studies and discussions on the topic of the death penalty, in the process giving his book added credence.

Perhaps some of my colleagues or our readers could let us know whether there is a good volume (or at least article) on the historical intersection of religion and the death penalty in the United States. There’s a book by Harry Potter (not the wizard) on the subject in Britain (Hanging in Judgment).

Last week, Ohio executed Dennis McGuire, who raped and murdered Joy Stewart in 1989. Because European manufacturers blocked the sale of pentobarbital for use in executions, Ohio used a new combinations of drugs which took far longer than average to kill McGuire. “He started making all these horrible, horrible noises, and at that point, that’s when I covered my eyes and my ears,” said McGuire’s daughter. Naturally, a statement on behalf of Stewart’s family observed that the executed killer received far more humane treatment than did his victim.

From my vantage point there are no persuasive reasons for the retention of the death penalty. Certainly, it satisfies a basic and very understandable desire for justice and vengeance, but justice in at least nearly all instances can be served in other ways. It is frankly hard to know whether the death penalty deters crimes, but my sense is that there is no conclusive evidence that it does. What is clear is that the death penalty leads human beings into — at least in too many instances — unnecessary legal and moral quagmires.

That the Hebrew scriptures command the death penalty for a fair number of offenses is hardly a compelling reason for Christians to support capital punishment as it exists today. Do we really want the execution of false prophets? The New Testament suggests (Romans 13) that governments have the authority to act as “agents of [God’s] wrath to bring punishment on the wrongdoer.” That doesn’t explicitly sanction the death penalty, but I imagine wrath might involve death. Still, even if Scripture assigns governments the right to impose the ultimate penalty, it does not mean that it is wise for them to do so or for Christians to support its imposition.

As a matter for reflection, the death penalty resembles abortion. The more thought and examination it receives (especially where the gory details are concerned), the less palatable it seems. Data suggests that many young evangelicals are changing their minds about homosexuality and gay marriage, but not about abortion. I couldn’t locate survey data on young evangelicals and the death penalty, but evangelicals as a whole are disproportionately supportive (this may have as much to do with geography and other political factors as religion and theology per se). Nevertheless, if young evangelicals move in a abolitionist direction on capital punishment, it could spell the end for the second incarnation of death row in the United States. I hope Exile and Embrace will prompt some evangelicals to rethink their support for an institution we could live better without.