The National Football League (NFL) playoffs begin this weekend. Over the next several weeks, twelve teams–six from each conference–will contend for a chance to play for the Lombardi Trophy in Super Bowl XLVIII, held at the MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford, NJ. Holding a virtual monopoly on professional football in North America, the NFL manages its brand carefully, cracking down on both on and off-field violations it deems harmful to its image. Within its monopoly, it also runs a tightly-regulated talent market in order to maintain a certain level of competition between matched up teams on “any given Sunday.” Despite a spate of scandals, serious questions regarding player safety, and a host of of bad actors, these factors have helped the NFL achieve popularity beyond its progenitors’ wildest expectations.

Beginning with the first Super Bowl (held in 1966) and the merger of the AFL and NFL (completed in 1970), professional football has gradually displaced baseball as America’s favorite sport over the past half-century or so. Although baseball enthusiasts demur, the NFL clearly has the corner on per-game-attendance and national television ratings. Most likely, the 2014 Super Bowl will once again reign as the most watched television event of the year. Further, through the trickle-down effect, more than twice as many high school boys play football than baseball. Football also excels beyond baseball in its aggressive marketing plan, a plan The New York Times once called full of “bombast and an abiding nationalistic spirit.” Without a doubt, by the end of the 1980s, professional football players competed on an immense stage with an enormous audience. As such, they were uniquely positioned to address a significant portion the population, most of whom were men. For the ever-entrepreneurial evangelicalism, the growing popularity of professional football provided another opportunity to connect with that audience.

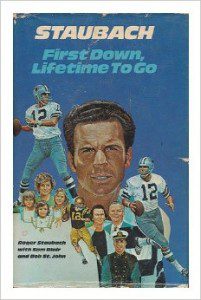

In the emerging American religious marketplace of the colonial period, evangelicalism appealed directly to the populace with the message of the new birth through dynamic preaching  and personal dynamism. The success of these efforts provided a “new model of leadership” wherein success came from the ability to connect with the people.* In the last quarter of the twentieth century this model of leadership coalesced with the growing popularity of professional football. As professional football players increasingly garnered popular attention, evangelical ministries and publishers promoted Christian players in order to promulgate the gospel. As a boy growing up in Texas, I clearly remember reading Roger Staubach’s twin autobiographies: First Down, Lifetime to Go (1974) and Time Enough to Win (1980).** Published by evangelical publishers, both focused quite a bit on Staubach’s commitment to Christ providing a strong contrast to the shenanigans of many of the other 1970s era Dallas Cowboys.

and personal dynamism. The success of these efforts provided a “new model of leadership” wherein success came from the ability to connect with the people.* In the last quarter of the twentieth century this model of leadership coalesced with the growing popularity of professional football. As professional football players increasingly garnered popular attention, evangelical ministries and publishers promoted Christian players in order to promulgate the gospel. As a boy growing up in Texas, I clearly remember reading Roger Staubach’s twin autobiographies: First Down, Lifetime to Go (1974) and Time Enough to Win (1980).** Published by evangelical publishers, both focused quite a bit on Staubach’s commitment to Christ providing a strong contrast to the shenanigans of many of the other 1970s era Dallas Cowboys.

In the post-World War II era, utilizing celebrity popularity to garner interest in the gospel became a staple in the evangelical playbook. Campus Crusade for Christ implemented this strategy in campus ministry*** and Billy Graham employed it in his crusades. In the 1980s, as several professional football players proclaimed for Jesus Christ, they were likewise promoted by various groups such as Athletes in Action, Fellowship of Christian Athletes and mega-churches as part of concerted efforts to reach non-believing football fans. In the 1990s, a conglomerate of ministries worked together to promote an evangelistic half-time program produced by Pat Robertson’s Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN). Intended to be shown as an evangelistic alternative to the scheduled half-time show by churches holding Super Bowl parties, the VHS-format program included testimonies by players participating in that year’s Super Bowl. Too many times, the player testimonies were prosperity-gospel-lite fare. Their success on the field came because they honored God… and he honored them right back. One year, the evangelistic Super Bowl half-time program prominently featured Dallas Cowboys wide receiver, Michael Irvin. Later, his off-field problems became well-known.

During this same period, evangelicals quickly attached themselves to such figures as Evander Holyfield, Hulk Hogan, and Andre Agassi–all of whom made explicit affirmations of faith in Christ at one point. Subsequently, one renounced his faith, another showed poor judgement at best, and another admitted to fathering several children out of wedlock. To be sure, as Jonathan Edwards argued in Religious Affections, each of these men–and many more like them–might be truly converted. Further, my own decisions and actions too often bring dishonor to Christ. But the manner in which American evangelicals, as a group, tend to flock to celebrities who give the slightest indication of being Christians demonstrates a problem endemic to the movement as a whole. In the eighteenth century, our forebears responded to the dynamic preaching of theologically-trained men of (mostly) proven character. Soon, “the new model of leadership” meant personal charisma and dynamism were necessary components for evangelical leadership. Today, I wonder if they are deemed sufficient.

*Mark A. Noll, A History of Christianity in the United States and Canada (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1992), 112. I have written more on this topic here.

**Staubauch’s “co-writers,” Sam Blair, Bob St. John, and Frank Luska, are clearly indicated on the cover of each book.

***On this topic, Bill Bright and Campus Crusade for Christ: The Renewal of Evangelicalism in Postwar America (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2009) by fellow Anxious Bench Blogger John Turner.