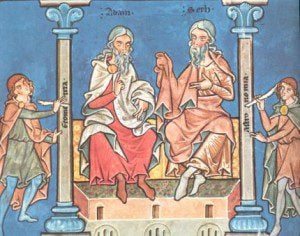

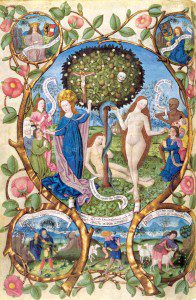

I have a long-standing interest in apocryphal and non-canonical Christian writings. Many of these texts present themselves in the words of Old Testament figures like Adam or Moses (the pseudepigrapha), and Old and New Testament characters and stories merged together freely over the centuries. Eve, for instance, is in one story an early visitor to Mary after Jesus’s birth. The Magi find their gifts in the Cave of Treasures, where they were originally deposited by Adam and other patriarchs. Adam’s son Seth planted the seeds that ultimately became the wood of the cross. Writers try to fill out every gap in a character’s back-story.

Some modern-day examples illustrate the kind of cultural curiosity that drives such a process of intertextuality and cross-referencing, although they are not ones that usually feature in Biblical or extra-Biblical scholarship. Bear with me in this thought-experiment.

Popular culture regularly produces figures or works that seize the imagination, heroes like James Bond or Batman, mythological worlds like Star Trek or Star Wars. Initially the works stand alone, but their respective worlds soon expand to include spin-offs and sequels, prequels and origin stories. Perhaps these offshoots develop the principal character and supply more information on his or her deeds, or else minor figures expand to become central to new works and series. Individual characters migrate into other genres and mythologies.

Beyond expanding the original tales, such addenda often take the mythologies in new forms of media – perhaps from books to films and games, comic strips or comic books and, most recently, on the Internet. Those later manifestations can in turn generate new books.

All become part of the expanding universe of that particular set of tales and legends, which is endlessly flexible. It might be updated to accommodate new public trends or interests, or to respond to major events in the wider world. Comic book characters might find themselves drafted to fight in a current war or international crisis.

Such add-ons might stem from the original creators, but often they are carried on by other hands. In a modern context, the capacity to create such additional works is strictly limited by copyright law, but even that constraint does not prevent ordinary people generating their own efforts, in the form of fan fiction. If people are not offered the story lines and outcomes they want to see or read, then they generate their own. Readers abhor a vacuum. Or, to adapt Stewart Brand’s famous dictum, information about other worlds wants to be free.

Over time, the boundaries between “core” texts and apocryphal creations fade to near insignificance.

I am well aware of the limits of such analogies, not least in terms of technology, and the speed of cultural change. Influences and adaptations that today take months might in earlier eras have spanned decades. But then and now, successful and beloved stories inevitably generate complex apocryphal universes, which span different types of media.

The key difference from the modern world, of course, is that early and medieval writers were dealing with concerns that went far beyond mere playful curiosity, as they believed they were addressing central issues of meaning and salvation. But the way they told and retold their stories was quite similar.