Last weekend, Germany celebrated the twenty-fifth anniversary of the end of the East German government’s blockade of its own citizens. In November 1989, amid considerable political confusion, East German security forces did not prevent crowds from crossing the border and scaling the Berlin Wall.

It was not the first moment in which East German soldiers chose not to fire at a critical moment. Because it transpired away from Berlin, most outsiders have forgotten the critical role that a Lutheran Church in the city of Leipzig played in “die Wende” (“the change,” the German term for the collapse of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik and the transition to a unified country under the West German political and economic order).

It was not the first moment in which East German soldiers chose not to fire at a critical moment. Because it transpired away from Berlin, most outsiders have forgotten the critical role that a Lutheran Church in the city of Leipzig played in “die Wende” (“the change,” the German term for the collapse of the Deutsche Demokratische Republik and the transition to a unified country under the West German political and economic order).

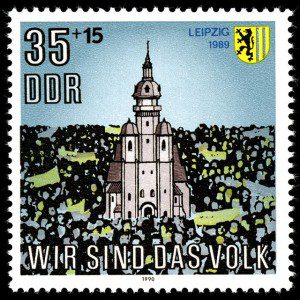

Leipzig’s venerable Nikolaikirche was the center of the Monday Demonstrations that eventually spread to other East German communities. Beginning in 1982, the church had hosted weekly “prayers for peace” on Mondays, initially welcomed by the dictatorship because they criticized the arms race (which, in the context of the early 1980s, meant criticism of Reagan Administration). Later in the decade, under the leadership of minister Christian Führer, the church attracted the participation of regime critics, including individuals who expressed a desire to leave East Germany. The prayer meetings began to spill over into public protests.

Starting in May 1989, party authorities took measures to prevent attendance at the Monday prayers, closing roads and making it difficult for residents of nearby communities to reach the church.

The protests, however, continued to grow, and government authorities began a crackdown. On Saturday, October 7, the fortieth anniversary of the DDR, demonstrators tried to march from the church. Police used water cannons and dogs. They arrested and beat protesters.

The Monday prayer meeting two days later was a tipping point. From the Telegraph‘s obituary of Führer, who died this past June:

In preparation for the weekly vigil scheduled to take place two days later, police warned that protests would be put down “with whatever means necessary.” In anticipation of violence, paratroopers were flown in and hospitals cleared for an expected influx of patients, specifically ones with gunshot wounds.

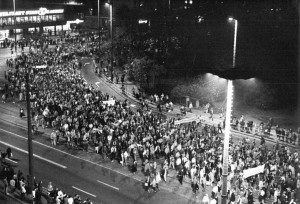

On the evening of October 9, what began as a few hundred gatherers at the church swelled to more than 70,000 in the streets outside. At the urging of Führer and other speakers, however, the protest remained nonviolent and the crowd, clutching candles and flowers, marched through the city in a peaceful demonstration, chanting the slogan Wir sind das Volk! (“We are the people!”) as armed soldiers looked on.

Apparently the East Germany government was surprised by the size of the demonstration and had not given clear orders as to how police should respond. Two weeks later, the size of the crowds in Leipzig reached 300,000. In its failure to crush the Leipzig protests, the East German government signaled that it felt powerless to stop the revolution and would not use violence to do so. “We were ready for anything, except for candles and prayer,” said one East German official.

The Leipzig revolution was surprising. As Anne Applebaum demonstrates in her The Iron Curtain, a top priority for the Soviet-controlled East European party dictatorships was to eliminate, subordinate, or coopt autonomous institutions and spaces. “The nascent totalitarian states,” she writes, “could not tolerate any competition whatsoever for their citizens’ passions, talents, and free time.” In particular, East European communist regimes needed to coopt and control churches, which had the potential to mobilize opposition. For example, in 1946 East German communists in Saxony grew alarmed when churches organized their own “youth retreats and summer camps.” Soviet soldiers “marched into the forest and … ‘brought the children home.'”

From the start of the Monday demonstrations, Stasi agents sat in the pews during the prayers and dutifully filed reports. Once the protests began to swell, Stasi agents and party members went early to the church to claim all of the seats so that regime critics could not attend. Führer later wrote that he loved preaching the Sermon on the Mount to these infiltrators (what follows is my rough translation / paraphrase):

They [the party members] had their assignment as did the Stasi workers, always present in large numbers at the peace prayers. But no one had realized or considered that they were exposing these men to the Gospel!

I always regarded it positively that the many Stasi workers heard the beatitudes of the Sermon on the Mount Monday after Monday. Where else would they hear them?

And so all these people, including SED-party members, heard the Gospel of Jesus, whom they did not know, in a church, with which they had no idea what to do:

They heard from Jesus,

who said, Blessed are the poor! And not, who has money is happy.

who said, Love your enemies! And not, down with one’s enemies.

who said, The first shall be last! And not, nothing will ever change.

According to Führer, these agents of the state would then go out and see men and women with candles in their hands, holding them with both hands, not holding any stones or weapons. Führer suggests that potential state agents of violence could not resist Jesus’s spirit of non-violence.

Certainly, the revolution in Leipzig and Berlin remained peaceful in large part because the regime was paralyzed with confusion and uncertainty, especially after Erich Honecker’s October 1989 abdication. Prayers and candles, however, filled the protesters with both peace and courage, courage that the regime’s efforts could not extinguish in the months leading up to the DDR’s collapse. The regime penetrated and partly neutralized the East German church, but it could not fully control the church, inadvertently leaving space for Christian Führer and a revolution that stunned both East and West with its quick and peaceful success.