In 1973, Geza Vermes reminded us, indelibly, that Jesus was a Jew, and subsequent generations of scholars have thoroughly absorbed that lesson. Less effective, though, have been statements that early Christianity also operated in a thoroughly Jewish matrix, and that the separation between the two movements was slow, uneven and patchy. Long after the first century, Christians tended to be found in regions and centers where Jews already existed, and relations between the two groups varied enormously in warmth and sympathy. In 1992, James Dunn edited a collection of essays on the theme The Parting of the Ways AD 70 to 135. In 2003, Adam Becker and Annette Yoshiko Reed edited their collection on the dissenting theme of The Ways That Never Parted: Jews and Christians in Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages.

That continuing relationship has major consequences for how we understand the early growth of Christian communities, and where we look for them. In the century or so after Jesus’s time, the movement’s best-known centers were in the Jewish heartlands of Palestine, Syria and Egypt, with Jerusalem and Alexandria as by far the most important cities. That obviously changed somewhat with the multiple wars, massacres and revolutions between 66 and 135, but scholars naturally look to Alexandria as a likely home for many early thinkers and writers.

Rather lost in this picture are developments east of the Roman Empire, in Babylonia, or what would later be called Iraq. In my book Lost History of Christianity, I emphasized the early and vigorous appearance of Christian communities in that country, certainly no later than the first century, and Iraq became a crucial base for later expansion into Asia. Mainly for reasons of space, what I did not stress there at sufficient length was the immense importance of Judaism in that part of the world, which provides the essential context of that upsurge. For centuries, in fact, Iraq had an excellent claim to stand as the capital of the Jewish world, and without appreciating that, we cannot understand how eastern Christianity emerged and grew.

A chronology might help here. (Jewish readers please note: I know this is a very basic account). Between about 180 and 220AD, Jewish scholars compiled the oral Torah in the great collection called the Mishnah, which was assembled in Palestine. This was the great monument of what we call rabbinic Judaism. Further commentaries and elucidations appeared in the Jerusalem Talmud, in the fourth century. Finally, chiefly between the fifth and seventh centuries, we find the Babylonian Talmud, which was assembled by scholars living in that country. From the sixth through the eleventh centuries, Babylonia was the setting for the Talmudic (Geonic) academies, At that point, Babylonia was the indisputable center of Judaism.

Why Babylonia? Jews had of course been settled there during the exile of the sixth century, and a community had always remained. Jews flourished during the Seleucid Empire that ruled the land from the fourth century through the second, and then under the Parthian Empire that conquered Babylon around 160BC. Jewish numbers grew with exiles fleeing from the Jewish Revolt onwards. The Parthian regime actively favored the Jews, not least because they were such fierce enemies of Rome. Jewish influence was particularly strong in the border states and petty kingdoms separating Parthia and Rome: in the first century AD, the king of Adiabene converted to Judaism.

That Jewish presence continued under the new dynasty that took power in the third century AD. To quote the Jewish Encyclopedia, “It was … before the accession of the Sassanids that the powerful impetus toward the study of the Torah arose among the Jews of Babylonia which made that country the very focus of Judaism for more than a thousand years.” We can actually date this move fairly exactly, as it was in 219 that the renowned scholar Abba Arika moved from Palestine to Babylonia.

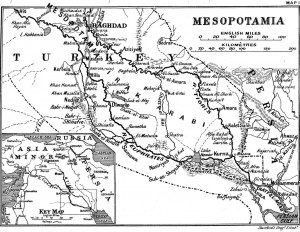

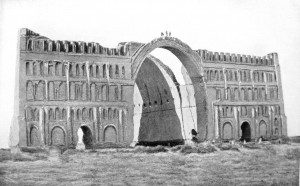

Just a word on geography. Unlike Egypt, Babylonia had no one single city to provide continuity of learning and culture. The city of Babylon itself flourished until 275BC, when the Seleucid kings built a new capital at Seleucia on the Tigris. The Parthians then built their new capital just across that river, at Ctesiphon. For some centuries, Seleucia-Ctesiphon was the world’s largest city.

Finally, in the eighth century, the Muslims created a lasting capital at Baghdad.

Despite all these changes, though, the same places along the Tigris and Euphrates rivers supplied cultural continuity. The greatest Jewish center was Ctesiphon itself. The rabbis who compiled the Babylonian Talmud came from cities like Mahoza or al Mada’in, between Seleucia and Ctesiphon; from Nehardea on the Euphrates; and from nearby Pumbeditha, which is now the war-ravaged modern community of Fallujah. The Pumbeditha academy operated from 258 AD through 1038. Further south, another prestigious academy at Sura looked to the heritage of Abba Arika.

This story is critical to the development of Judaism, especially in its rabbinic forms. More to the point, it is also, almost exactly, the history and geography of Christianity east of Syria, and of that great Church of the East that ultimately spread its power over much of Asia.

More in my next post.

On the Babylonian Talmud, see now Shai Secunda, The Iranian Talmud: Reading the Bavli in its Sasanian Context (2014).