Americans incarcerate. So begins and ends Jennifer Graber’s The Furnace of Affliction: Prisons & Religion in Antebellum America.

Americans incarcerate. One of out every hundred American adults is behind bars. One would rather not think about the economic, emotional, and spiritual cost of this mass imprisonment. I imagine that most Americans and most American Christians would prefer to think that policies of mass imprisonment have reduced crime rates. After all, rates of violent crime have been falling in recent years.

Still, nearly all Americans would probably agree that 2.3 million prisoners is far too many. Indeed, despite the ongoing appeal of tough-on-crime policies, criminal justice reform has some potential to unite voices on the political right and left.

Once American governments started building large prisons, ministers and other Christian leaders wanted to enter them, believing that they are especially well positioned to rehabilitate prisoners. Especially in recent decades, moreover, smaller religious groups have identified prisons as centers for recruitment. “The first thing I noticed after beginning my sentence — for five counts of armed robbery, a consequence of heroin addiction,” wrote Daniel Genis in a recent Washington Post op-ed, “was how many faiths were represented.” Genis observes that whereas Catholic priests were rare (outside of state-employed chaplains), Nation of Islam men were common.

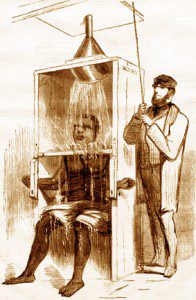

How did we get to this point? Jennifer Graber explains much of the backstory in The Furnace of Affliction: Prisons & Religion in Antebellum America (2011, but just released in paperback). Perhaps most readers of this blog may not know that mass incarceration is a fairly recent idea. Criminals through the eighteenth century were likely to suffer quick and violent punishment, or perhaps public humiliation. (Holding pens typically did just that — hold suspects prior to trial). Even earlier, churches often played a significant role through ceremonies of public penance, though this became rarer in the colonies after the seventeenth century. With rising levels of urbanization, though, states in the Early Republic established prisoners designed to simultaneously punish and reform criminals.

In New York (the focus of Graber’s book), Newgate Prison “welcomed” its first inmates in 1797. Newgate was the brainchild of Quaker reformer Thomas Eddy, who had once spent a week in a decrepit holding pen. Eddy believed that Newgate could serve as a “garden” of rehabilitation through labor, cleanliness, nutrition, companionship, and only mild forms of punishment. At the same time, the prison’s workshops were supposed to turn a profit. Eddy’s idealism quickly collided with the realities of prison overcrowding. “Newgate’s inhabitants were not Quaker children,” Graber observes wryly. Eddy was soon gone, and punishments were no longer mild.

Other prisons followed, such as Auburn and Sing-Sing. And other Protestant chaplains and reformers followed in Eddy’s wake. As prisons meted out harsher and harsher punishments, those religious figures faced an irresolvable conundrum. They could sharply criticize prison conditions and lose access to prisoners. Or they could work within the system. Working within the system, however, meant at least the tacit endorsement of brutal forms of punishment and deprivation. Men such as Baptist Reverend John Stanford, in contrast to Eddy, understood the prison as a “furnace of affliction.” But how hot should that furnace be? Over time, many Protestant chaplains apparently accepted that prisoners deserved intense affliction, suffering that their crimes had merited and that might produce conversion. Penitentiaries, though, typically broke the bodies and minds of inmates without helping them make much progress toward spiritual redemption. By making themselves present, Protestants made themselves complicit. “Even as the New York prisons became earthly hells,” Graber writes, “the reformers insisted that Christian prisons were still possible if the right people led them and the right practices were put in place.”

followed in Eddy’s wake. As prisons meted out harsher and harsher punishments, those religious figures faced an irresolvable conundrum. They could sharply criticize prison conditions and lose access to prisoners. Or they could work within the system. Working within the system, however, meant at least the tacit endorsement of brutal forms of punishment and deprivation. Men such as Baptist Reverend John Stanford, in contrast to Eddy, understood the prison as a “furnace of affliction.” But how hot should that furnace be? Over time, many Protestant chaplains apparently accepted that prisoners deserved intense affliction, suffering that their crimes had merited and that might produce conversion. Penitentiaries, though, typically broke the bodies and minds of inmates without helping them make much progress toward spiritual redemption. By making themselves present, Protestants made themselves complicit. “Even as the New York prisons became earthly hells,” Graber writes, “the reformers insisted that Christian prisons were still possible if the right people led them and the right practices were put in place.”

Moreover, reformers and chaplains largely agreed to limit their messages and materials to generic forms of Protestantism (at most) and avoid the particulars of their traditions. Graber notes that “Protestant prison reformers contributed to institutions with all the trappings of religion but no Protestant particulars.” By the eve of the Civil War, few Americans viewed prisons as either Eddy’s garden, and not as many saw any redemptive value in inmate suffering. Most simply saw prisons as institutions designed to punish offenders with the hope that former inmates might become law-abiding citizens. Moreover, those institutions began to make space for particular ministries to Catholic inmates, welcome phrenologists, and invite visitors who would read Charles Dickens instead of the Bible to prisoners. By so assiduously carving out a place for religion in prisons, Protestant chaplains and reformers inadvertently contributed to the secularization of the space in which they worked. Nonspecific forms of Protestantism eventually led to Protestantism’s disestablishment.

This last argument makes a well-reasoned contribution to a growing literature on the relationship between Protestantism and secularism in America. Graber herself cites the work of John Lardas Modern. Graber’s conclusions also remind me of George Marsden’s arguments in The Soul of the American University, in which he discusses how so many public and private colleges and universities eventually divested themselves of the nonspecific forms of Protestantism they had once worked so hard to establish. Religion, though, plays a much larger role in contemporary prisons than it does on most American campuses (though it is not inconsequential there either). Genis suggests that religion is a visible and potent force in American prisons. But even though conditions in American prisons are far more humane than in the nineteenth century, I imagine that few chaplains and reformers approach prisons with anything approaching Thomas Eddy’s idealism. They know better.