The heresiography (or heresiology) is something of a dying genre among Christians today.

For centuries, though, heresiography was a staple of Christian literature, as those who contended for their understanding of orthodoxy theology catalogued the theological sins of others. To give a recent example, through at least most of the twentieth century, conservative Protestants in the United States (and some elsewhere) wrote heresiographies about what they termed “heresies,” “isms,” and — increasingly the preferred term — “cults.” Walter Martin, perhaps the most influential of such countercult authors, defined “cultism” as “the adherence to doctrines which are pointedly contradictory to orthodox Christianity and which yet claim the distinction of tracing their origin to orthodox sources.” For many evangelicals, of course, orthodoxy meant evangelical theology. Heresiology remains important within the evangelical world, but I would argue — as has my colleague Philip Jenkins — that it does not have the quite same salience that it did during the twentieth century, especially during the last great “cult scare” that began in the 1970s.

The Panarion of Epiphanius is one of the most famous or infamous early hersiographies. Scholar of early Christianity Frank Williams has made the entire text available in English in two volumes recently published in revised editions by Brill. Williams worked from the critical Greek text prepared by early twentieth-century German scholar Karl Holl. The information below is mostly gleaned from his introduction; the quotes are from his revised text.

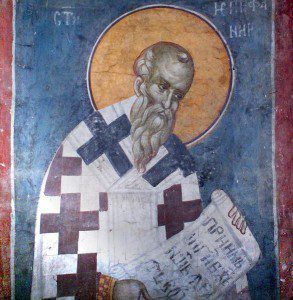

Epiphanius was a Palestinian-born Christian who became bishop of the Cypriot city of Salamis around the year 367. He was a fiery defender of the Council of Nicea’s affirmation that Jesus Christ was “of the same substance” of God the Father. The council, however, had hardly eliminated intra-Christian theological conflict. Although the council had condemned the position of Arius, many of his supporters continued to espouse the belief that “there was a time when he [Jesus Christ] was not.” Epiphanius was also concerned about two other matters: the influence of Origen; and the use of images as objects of devotion in churches.

Active during the first half of the third century, Origen contended for the subordination of the Son/Word of God to the Father, the pre-mortal existence of human souls, and the possibility of universal salvation. By the fourth century, in the wake of Nicea, Origen’s writings were increasingly controversial; in the year 400, a council in Alexandria condemned “Origenism.” Needless to say, Epiphanius was very concerned about “Origenism.”

Around the year 375, Epiphanius began composing what became known as the Panarion, an encyclopedic study of eighty “sects.” He explained that “panarion” means “chest of remedies for those whom savage beasts have bitten.” Among the eighty sects (Epiphanius chose the number from a reference to “fourscore concubines” alongside “threescore queens” in the Song of Songs), Epiphanius included pre-Christian phenomena such as “Judaism” and “Hellenism.”

Mostly, though, Epiphanius aimed his words at gnostics, followers of Arius and Origen, Manichaeans, and the followers of Montanus and other prophets, tracing their origins and genealogies, refuting their arguments, and denouncing their practices. He intended to rescue heretics from their delusions and inoculate Christians against theological threats. In service of this aim, Epiphanius repeated scurrilous rumors about sects he deems heretical and denounces them in strident terms. In a prologue to his work, Epiphanius begged forgiveness for calling “certain persons ‘frauds,’ or ‘tramps’ or wretches.'” Too much was at stake to mince words, he maintained. Praising his refutation of a Montanist sect, Epiphanius rejoiced that he had “squashed a toothless, witless serpent like a gecko.” Apologies for intemperate language aside, Epiphanius reveled in squashing heresies.

The Bishop of Salamis saved some of his harshest words for Origen, prefacing his theological refutation with a rather savage ad hominem attack. According to Epiphanius, Origen was perverse in his doctrine, character, and sexuality. First, he observed that after initially responding bravely to persecution, Origen buckled. When Roman authorities gave him a choice between being rape by a black slave and sacrificing to pagan gods, he chose to sacrifice. More pointedly, Epiphanius suggested that Origen could not overcome relentless sexual temptation through self-control. Thus, he mutilated himself or used “a drug to apply to his genitals and dry them up.” Epiphanius was unsure. “Though I have no faith in the exaggerated stories about him,” Epiphanius allowed, “I have not neglected to report what is being said.” Epiphanius was not the first sloppy journalist, but my goodness.

Of course, Epiphanius vigorously opposed Origen’s teaching as well, rejecting Origen’s deprecation of material, embodied existence and affirming the literal physical resurrection of both Jesus and human beings. “And you too, Origen,” the Epiphanius concluded, “with your mind blinded by your Greek education, have spat out venom for your followers, and become poisonous food for them, harming more people with the poison by which you yourself have been harmed.” Epiphanius’s heresy-hunting zeal and unrestrained diatribes stained his reputation. “Of all the church fathers,” writes Frank Williams, “Epiphanius is the most generally disliked.”

Epiphanius, however, had advanced a genre of enduring importance, dedicating to preserving a single, normative body of Christian theology. His was not the first heresiography. Irenaeus had catalogued a number of gnostic sects in the late-second century. Needless to say, though, Epiphanius helped the genre catch on. In an age in which, to quote Peter Berger, heresy is “universalized,” few contemporary Christians have much sympathy for “heresy-hunters.” All human organizations, however, religious and otherwise, police the boundaries of acceptable belief, some more closely than others, and some more crudely than others. One might hope that in this process theological opponents might avoid Epiphanius’s rumor-mongering and intemperate language. Epiphanius certainly reminds us, though, that what seem to many moderns to be arcane theological debates mattered intensely to many early Christians. And for better or worse, the Panarion is certainly colorful enough to grab the attention of readers more than sixteen centuries later.