Two weeks ago, I began a discussion of Colleen McDannell and Bernhard Lang’s Heaven: A History, in which they trace two millennia of Christian ideas about the afterlife. To what extent does human community persist in heaven? Does the hereafter, moreover, take place on earth or in heaven?

Last time, I discussed M&L’s discussion of biblical understandings of death and heaven as found in the Jewish scriptures and New Testament. This week, our focus shifts to early and medieval Christianity.

M&L begin this section of their book by contrasting the views of Irenaeus (the second-century Bishop of Lyons) and Augustine. Irenaeus lived at a time when Christians faced periodic waves of persecution, violence, and possible martyrdom. M&L suggest that Irenaeus correspondingly “looked to the next world for compensation for the loss of productive life on earth.” Irenaeus coupled a firm belief in the bodily resurrection with belief that Christians would live on a renewed earth during the millennial reign of Christ. (M&L see a link between martyrdom and millenarianism). Irenaeus rejected an allegorical reading of apocalyptic scripture, and he foresaw a new world in which the soil and the Saints enjoyed remarkable fertility and enjoy feasts of remarkable bounty.

Augustine lived in the fourth and fifth centuries, at a time when Christians feared the Roman Empire’s collapse rather than its power. After an adolescence of indulgence, the converted adult Augustine embraced an ascetic lifestyle. Irenaeus’s idea of an earthly paradise, with fertility and feasts, held little appeal. Instead, in his On Faith and the Creed, Augustine spoke of celestial bodies without “flesh and blood.” “Everything must be spiritual,” he wrote. Future happiness did not depend on any sort of human society: “Whoever knows you [God] and others besides, is not happier for knowing them, but is happy for knowing you alone.” For the early adult Augustine, M&L conclude, heaven “was the continuation of an ascetic retired life. It was a world of immaterial, fleshless souls finding rest and pleasure in God.”

Later in life, especially in City of God, Augustine at least partly revised his views. Certainly, eternal bliss meant the beatific vision of seeing God. Eternity meant an eternity of praise and love of the divine. The idea of the community of saints enjoying God together became more important, though. And those saints could enjoy each other’s company. Augustine became more open to the idea of heavenly family reunions and to the idea of heavenly flesh. Augustine preserved a theocentric heaven, but a heaven in which family and community played roles as well.

Naturally, the idea that bodies would persist raised all sorts of questions. Would there be sexual differentiation? Yes, said Augustine. Men and women would be in their natural state without shame and without defect. Would there be sex? No. Their bodies would inspire divine praise, not human lust. In this semi-spiritual heaven,” as M&L term it, “the soul united with the flesh in such a way that spirit dominated matter.” These sorts of question persisted into the medieval period and beyond. Would the saints be naked or clothed in robes? Augustine said naked. I hope it’s warm enough for my wife and cool enough for me.

Depending on their social locations and readings (or hearings) of scripture, Christians might think of the hereafter either in terms of a garden paradise or as the city of New Jerusalem. As European cities gradually developed, the latter idea became more attractive. Also, the desire to be reunited with one’s beloved steadily grew in power and became a fervent hope during the Renaissance.

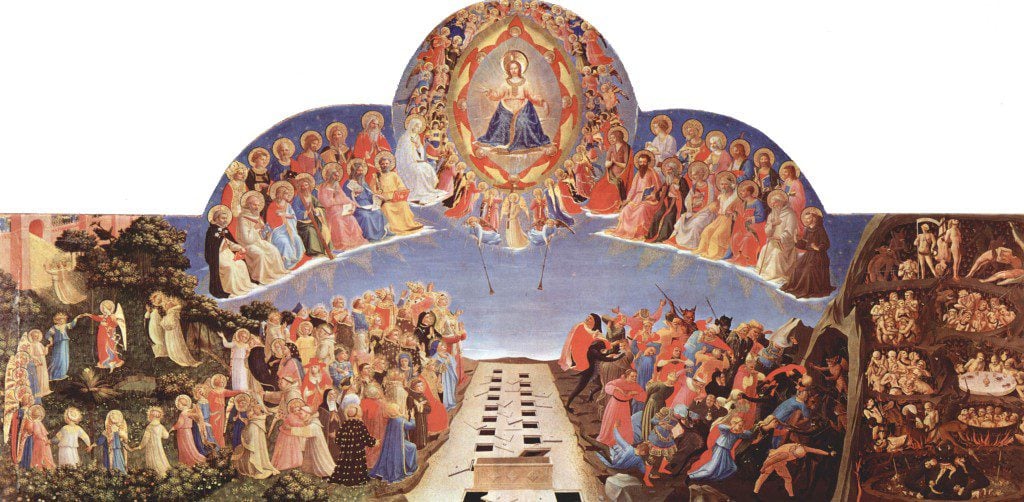

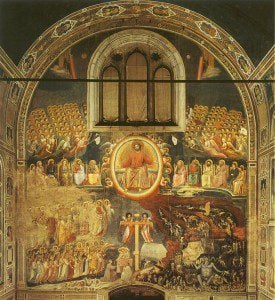

Medieval Christians frequently did not imagine heaven — or the heavenly city — in egalitarian terms. For example, Gerardesca, a thirteenth-century lay member of the Camaldolese order, imagined three primary areas of heaven. Only the Trinity, the Virgin Mary, the choirs of angels, and the holiest saints lived in the city proper. More distinguished saints — those with greater merit — lived in seven castles built on mountains surrounding the city. More minor fortresses housed the remainder of the faithful in the vicinity. Gerardesca, explain M&L, “experienced the new Jerusalem of the book of Revelation as a city-state of thirteenth-century upper Italy.” The idea that there would some sort of hierarchy of heaven was pervasive during these centuries. “The saints,” asserted the thirteenth-century Albertus Magnus, “will receive different degrees of clarity according to their different degrees of merit.” Aquinas taught that although all of the blessed would receive the beatific vision, they would “do so in various degrees.” Many medieval theologians, moreover, removed God to a higher heaven, a higher realm above that in which the blessed would reside.

There are many other fascinating medieval ideas worthy of discussion. For example, some female nuns and mystics anticipated their heavenly union with their bridegroom. The thirteenth-century Gertrude, who lived in a convent in Saxony, believed that female virgins would gain access “to the celestial bridal chamber.” Some visions of the love between human bride and divine bridegroom were chaste, others more erotic.

If many medieval theologians anticipated both the beatific vision and the communion of the saints, many Renaissance writers openly looked forward to an eternity of human love. Many such writers maintained heaven’s divine center, but according to M&L, human society gradually assumed a greater focus.

Some envisioned both a paradise garden and the New Jerusalem, without any sense that the former was a consolation prize for those who did not qualify for the latter. For some writers, the Classical ideal of the Elysian Fields assumed a renewed importance. They looked to Cicero as much as to St. John in describing the afterlife. Paradise would be a place of unbridled love of other people. Heaven also became less hierarchical, more dynamic. “If the heaven of the Middle Ages is essentially a cone with God at the top,” write M&L, “then the Renaissance heaven is a box with divine worship going on at the top and a paradise garden at the bottom. The two realms are not isolated from one another, but divine characters can move between the two.”

Eventually, the pendulum fell back toward a theocentric heaven during the era of the Reformation and Counter-Reformation, but the idea of a heavenly reunion of families, saints, and lovers had gained a foothold in the Christian imagination it would not easily relinquish.