I posted about the shifting frontiers and definitions of the ancient lands described in the Bible. At various times, they were either much larger and more expansive than what we think of in terms of modern Palestine, while on other occasions they were considerably smaller. I think we tend to lose track of this when we rely as heavily as we do on writings created within Jerusalem and its highly literate culture. At times, Jerusalem really was at the heart of a sizable empire, and others definitely not, but it’s really hard to tell the size of the world the writers are speaking to. It rather recalls the famous cartoon of the New Yorker’s view of the world.

So how did that Israelite universe change over time? I know I am walking into a scholarly minefield here, but the Bible attributes a sizable regional empire to David and Solomon n the tenth century BC, possibly touching the Euphrates. Many modern scholars are deeply suspicious of that idea, but let’s for the sake of argument agree that in the ninth century, Israel’s power stretched north and east of modern Palestine.

In the eighth century, the Assyrians destroyed the northern kingdom, leaving a Judah clinging tightly to the southern regions around Jerusalem. Often, when we read the prophets, we should think of them as addressing a quite tightly constrained Judah. The Persian province of Yehud Medinata likewise covered only a small portion of greater Palestine. Probably during the fifth century, the split between Jews and Samaritans consecrated a north-south division, symbolized by the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim.

During the third century, Greek observers had little difficult in understanding the Jewish polity as a familiar kind of Temple-run city-state, strongly based within Jerusalem.

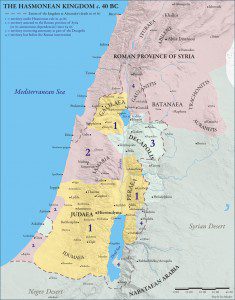

The most dramatic changes in the size and definition of the Jewish world occurred in the century or so following the Maccabean revolt of the 160s BC, under the Hasmonean realm. This was a time of withdrawal and near collapse for the old Hellenistic powers that had dominated the region, leaving a power vacuum. A series of conquering Jewish kings annexed most of what we would today call modern Israel and Galilee, and still more significant, they took significant possessions across the River Jordan. Although the Hasmonean state ceased to exist in the mid-first century, the empire they created was the Jewish and near-Jewish world of the later Second Temple era, the world known to Herod the Great and to Jesus’s apostles.

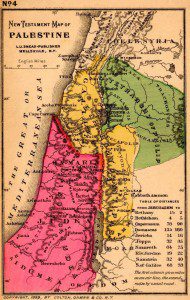

I will be using some maps here, but I will also illustrate my points by links to map sites where you can see those images in full detail. That’s partly a copyright concern, but the ability to magnify images is immensely useful.

(This map is the work of Ivan Mladjov, who has generously put it online for public non-commercial use).

To over-simplify the story, John Hyrcanus (134-104 BC) began his rule with just Judea and the land of Perea, immediately across the Jordan. He then more than doubled the size of his state by conquering Samaria, Idumea and Galilee (Map here). His son Alexander Jannaeus (103-76 BC) acquired most or all of Moab, Gilead, Iturea and other major possessions across the Jordan. He also enjoyed victories on the Mediterranean coast around Gaza and the ancient Philistine regions. (Map here). In modern terms, he gained large portions of the nation of Jordan, and his power stretched into Syria. This map gives an excellent idea of the very wide range of Jewish control at the end of his life. The Hasmoneans were, very briefly, a significant regional power.

(This map is in the public domain).

Political and military control was one thing, but that imperial outreach also fundamentally changed the nature of the peoples living within the Jewish orbit. When we read the New Testament, we often encounter Gentiles in the form of Roman military and occupation forces. It’s a picture that seems to make sense in terms of modern stereotypes of Empire, with occupying armies holding down oppressed nationalities, and few intermediaries between rulers and ruled. However, that world was a much more diverse community – ethnically and religiously – than we often think.

More next time.