All of my children got ashes on the forehead before getting washed with the waters of baptism.

All of my children got ashes on the forehead before getting washed with the waters of baptism.

This is probably common, depending on local protocols of baptism or Ash Wednesday, which more American Protestants now observe as an edifying if not essential rite. Our Anglican church schedules baptisms for the Easter vigil, so our kids had Lent before they got the sacrament. Some Protestant parents, who have embraced Ash Wednesday but not infant baptism, go years watching their children marked with an outward sign of their sinful mortality before they get to see the water of new life coursing over the brow.

I must admit that for me this does not go down easily. I deeply appreciate Ash Wednesday. Admittedly for Protestants observance of the day and of Lent altogether has an uneven history. Some reformers, from the sixteenth century on, rued its conspicuous display of penitence and its suggestion that you could fast your way into God’s favor. Others, like Anglicans, retained Lenten practices as instructional opportunities, helpful disciplines. Ashes on the forehead are helpful. It is good for me and I think for most people to be reminded that we are going to die, to have the ineluctable fact of our own mortality starkly and publicly presented. I would even argue that it is a rich gift to have this reminder of mortality offered, as it was last week in many American churches, when actual death—from starvation, migration, warfare–does not stand at the door.

But it is different to have that sentence read over your children. In lay Catholic conversations about whether young children should receive ashes (because young children cannot be said to have committed conscious sin or have ability to repent), answers usually lean affirmative. Some suggest that kids should be included in communal penance, or should begin it early as a way of growing up in faithful practice. Some even imply that kids would feel left out if not given their share of ashes.

I am not sure what reason motivated the mother kneeling next to me last Wednesday, in the Anglican church I attend, with her infant daughter on her hip. The baby was first facing away from the priest, who made a cross on the mother’s forehead and then proceeded on to me to remind me that I was going back to dust. To be sure, I should have had enough to think about with my own mortality but I could not help wondering if she had the baby facing the wrong way on purpose—to refuse ashes. I know the mother and decided to ask her about it later. But before the minister passed on to another penitent, the mother turned the child and he returned. The baby’s face was serene and eyes wide. The priest made a cross on her smooth forehead and told her she was going to die, and went on.

She did not quarrel or cry out. We all went back to our pews. But that hurt to watch. If, for Protestants, these penitential acts are better understood as educational rather than meritorious, what are we supposed to learn from reminder of our child’s certain death? The ashes on that baby’s head were not a word to the infant but served a pronouncement to her mother: remember that your child is dust, and to dust she will return. The mother might protest—as I remember silently insisting with my babies—no! she did not come from dust, she came from warm flesh, from me! She will go to dust—but she shouldn’t for a long time! Let life spare her; let the ashes come to me instead!

Seeing ashes on the face of that beautiful baby, mortal and subject to redemption, reminded me of the words Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead put in the mind of a dying father who had himself to entrust his son to God: “There are two occasions when the sacred beauty of Creation becomes dazzlingly apparent, and they occur together. One is when we feel our mortal insufficiency to the world and the other is when we feel the world’s mortal insufficiency to us.”

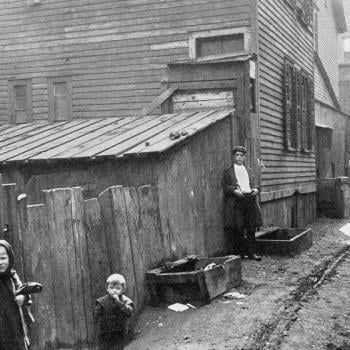

This is one of the painful gifts of grace that comes in this liturgical season. Having to reckon with the morality of your brothers and sisters, your sons and daughters, is as much part of the Lenten message as your own mortality. What the priest says about that child when he makes the smudgy cross is true. Your lovely new child enters as a creature in a gorgeous terrifying world ineluctably falling apart, devouring, decaying. That is the fact of earthly parenthood. This past year has generated shattering images of that suffering, worst of all perhaps the tragic, iconic photo from last September of a three-year-old refugee boy face down in the sand on a Turkish beach.

This is what all parents must confront, unblinking, and it is a hard truth better confronted in church. Church is the right place to admit our death-in-life, our incapacity even to protect our own children from sin, theirs or others. Ashes on their foreheads as well as our own are reminders of our fellowship together in this mortal life; they are co-heirs and co-laborers, not just our darlings. Our limits as parents encourages the entrusting of children to the motherhood of the church.