I have been working on European history in the later nineteenth century, and specifically the role of religious and apocalyptic ideas in shaping real-world politics in in that supposedly modern and technological age. I’ll be doing several posts on that topic in coming weeks, but let me just introduce the theme here. What I have to say is highly appropriate for the Palm Sunday weekend.

Even at the end of the nineteenth century, European elites were much more deeply immersed in messianic, millenarian and apocalyptic ideas than we commonly give them credit for, and those beliefs had still greater resonance among ordinary people. Contrary to stereotype, we easily find the strong survival in that era of “medieval” religious ideas that we often dismiss as long extinct. Those ideas emerged, for instance, in attitudes towards Islam, and “crusader” rhetoric was much in evidence in attitudes towards the Ottoman Empire. It is not surprising then that the language of holy war and crusade was still so powerful during the First World War era, a theme I addressed in my 2014 book The Great and Holy War.

Still, only a century ago, Christian Europe still had a lively ideology of holy war.

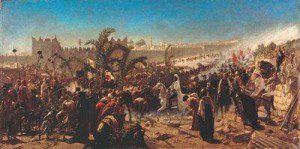

Just as a sample of these trends, I offer a celebrated German painting of the era, “Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm of Prussia enters Jerusalem in 1869,” by the Orientalist artist Karl Wilhelm Gentz. I reproduce a tiny image of it (public domain) but you can see a detailed version here.

Here is the background. In 1870-71, Prussia defeated France in war, leading to the proclamation of the Prussian King Wilhelm I as the Emperor of a new Germany. His son and heir was Friedrich Wilhelm, the Crown Prince depicted here.

Germany in that age had a fair claim to lead Europe in terms of intellectual, scientific and cultural achievement. The Crown Prince was a paragon of advanced liberalism, who wanted to combine German technology and science with British political and humanitarian views. For one thing, he loathed anti-Semitism. In 1888 he ruled, all too briefly, as Emperor Frederick III, before dying suddenly. He was succeeded by his much more aggressive son Wilhelm II, whom we associate with the First World War.

In 1869, European dignitaries gathered to celebrate the opening of the Suez Canal. On his visit to the area, the Crown Prince visited Jerusalem, where the Ottoman Sultan had granted land for a German church. In 1873, Gentz received a commission to depict the encounter, and the painting was first exhibited in 1876. Coincidentally, that timing gave the work added significance. Europe by 1876 was entering a period of high messianic excitement, with imminent hopes and fears that Ottoman and Islamic power might be expelled from Europe. Religious tensions and dreams ran high.

But look at the painting. The mighty Lutheran king is approaching the Damascus Gate, where prophecy asserted that a great Christian ruler would some day drive out Muslim power. And those are indeed palm branches that the locals are waving before him. Could the assertion of a Christ-like status be clearer? Typically, we see very few faces of local people – “the Orientals” – but the Crown Prince’s dignitaries, generals and clerics are all well represented.

Put this another way. A great king rules somewhere far away, and he has sent his son, heir and representative to enter the holy city. Are we talking about God and Christ, or Wilhelm and Friedrich Wilhelm? As scholar Karin Rhein points out, that the painting recalls Christ’s entry into Jerusalem is no coincidence (Deutsche Orientmalerei in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts). Indeed not.

Surely the word ”messianic” is legitimate here? What does this tell us about monarchical pretensions, even those of a strongly liberal-minded ruler? And then we think of what will happen when multiple rulers have those same aspirations. How many messianic rulers can Europe afford at any one time?

Friedrich Wilhelm’s own son Wilhelm made another visit to Jerusalem in 1898 and again staged a great triumphal entry, but that is another story. Scandalously, he persuaded Ottoman authorities to breach the city wall next to the Jaffa Gate in order to make an entrance large enough for his procession. When the British general Allenby finally took the city in 1917, he deliberately made his entry as modest and non-triumphal as possible, to highlight the contrast with these German predecessors.