While my job is to teach people about history, parenting our twins has made me realize how little I know about how to teach young children about history. But over the past two summers, I’ve spent a lot of time taking the kids to historical sites and museums, and that’s also been a big part of homeschooling them this fall, while we spend my sabbatical in southwestern Virginia. In fact, we just got back from a few days visiting memorials and museums in Washington, DC and the Gettysburg battlefield site in Pennsylvania.

So, knowing that I’m no expert in child development and that Lena and Isaiah might not be the most typical first graders, let me pass along six things I’ve learned about teaching history to six-year olds:

1. It’s a good deal

Raising children is expensive. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, my wife and I should expect to spend $25,000 per year on the twins. So we’re always on the lookout for relatively inexpensive experiences and activities.

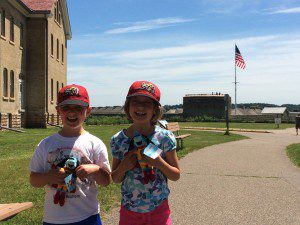

Fortunately, if you live in the State of Minnesota, you have access to one of the best deals in the world: a household membership in the Minnesota State Historical Society. Frankly, I would shell out those seventy-nine bucks if all they bought us was free entry to the world-class Minnesota History Center in St. Paul. But there are twenty-five other sites in the state. Just in the Twin Cities area that includes Historic Fort Snelling (at the strategic spot where the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers meet), Mill City Museum (built into the ruins of an old flour mill in downtown Minneapolis), and the Oliver Kelley Farm (a little slice of the 1850s in the northwest metro). This past summer, as we tried to accustom the kids to longer drives, we added visits to a museum of Native American history on an Ojibwe reservation, an iconic lighthouse on Lake Superior, and the house where Charles Lindbergh grew up.

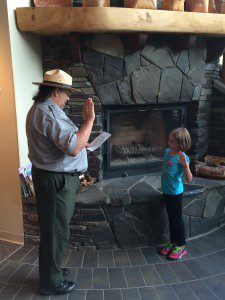

I know that ours is one of the best state historical societies in the country, but I’m sure that others offer similar kinds of opportunities for similarly affordable prices. And what we’ve also learned this summer is that the National Park Service does a wonderful job of engaging in public history for all ages, making possible free visits to everything from a fur trade post to a center dedicated to the folk music of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

2. Six-year olds learn by playing

At least in higher ed, “experiential learning” is one of those good ideas that gets oversold — chiefly by lazy, overgeneralized comparisons to other modes of pedagogy. Not every nineteen-year old actually learns well in this way.

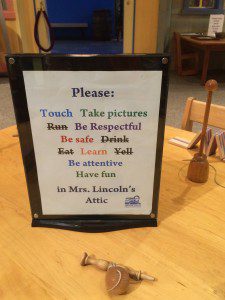

But six-year olds sure do! Just at the Minnesota History Center, Lena and Isaiah run up and down a grain elevator, reassemble a bison to learn how the Lakota used every part of that animal, and work on an assembly line from a WWII ordnance factory. They especially love to play with the games that their peers used in previous centuries, from corncob checkers at an Appalachian mill to the cup-and-ball game that they saw at both the Lindbergh House and the Abraham Lincoln Museum in Springfield, IL.

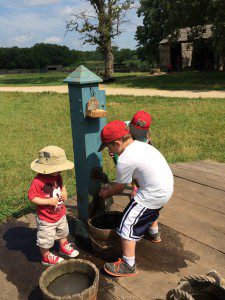

Their favorite is the water pump at the Kelley Farm. If it weren’t that every other child-visitor feels the same way, our kids would spend an hour filling buckets of water — which they then use to fill the cows’ trough, to water the tomatoes and beans in the garden, or to wash turnips in the kitchen. It gets them noticing how significantly life has changed in 150 years (more on that in #6 below), but let’s not overthink everything. When I asked Isaiah last year why he liked the pump best, he grinned back, “Because it squirted water!” (Duh.)

3. They’re sponges

When we were at the Lincoln Museum, we came to a recreation of the future president’s first attempt at running a business: a small store. One of the kids noticed a wool blanket and told me, “Oh, that cost three furs.”

It took me a moment to remember that we had received a lesson in 19th century blanket pricing two months earlier at the North West Company Fur Post in Pine City, MN. A historical interpreter playing the role of a French Canadian voyageur explained that the number of stripes and half-stripes on the blanket indicated how many beaver pelts it was worth.

Again, it might just be that my kids are a bit precocious in these matters, but my wife (who is trained as a pediatric occupational therapist and now directs children’s ministries at our church) tells me that kids this age have an astonishing capacity to retain information that quickly fades from my now-fortysomething memory. And seeking to make connections from site to site — better yet, embedding the information in a larger story — helps reinforce what they remember.

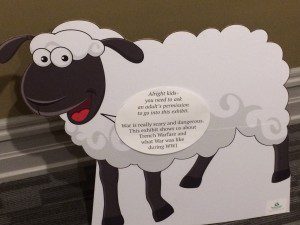

4. History is rated PG

Watching the responses of six-year olds has reminded me just how much mundane and extraordinary violence runs through human history. Isaiah is generally bothered by loud noises, so we won’t be taking a second trip on the eight-story elevator ride at the Mill City Museum, since it recreates a factory explosion that scared the poor boy half to death. And he never wants anything to do with the tornado simulation in the MN History Center’s exhibit on the history of weather. But even I’m unnerved by the sound of prairie winds beating against the thin walls of a white settler’s sod cabin on the other side of that museum. Both exhibits remind children (of all ages) that human history is worked out within physical environments that defy our delusions of control and security.

I’ve had to be especially cautious with exposure to one of my own fields: military history. Thanks to an early encounter with an illustrated Bible, our children associate soldiers with the Crucifixion, so I knew they’d be leery of the historical interpreters taking target practice at Fort Snelling. Fear of soldiers plus fear of loud noises made it hard for Isaiah to enjoy the Civil War exhibits either at the Lincoln Museum or the visitor center at Gettysburg.

And while we weren’t able to get tickets to the new Smithsonian Museum of African American History during our jam-packed one-day visit to Washington’s National Mall, I would have hesitated to take either of our kids through a historical survey that immersed visitors in the dehumanizing violence that made possible the institutions of slavery and segregation.

5. Children are capable of thinking historically

Not every engagement with the past is actually “history.” So glad as I am that the kids generally have fun with these historical field trips, I’ve also been curious to see how Isaiah and Lena thought about what they were experiencing. Did they demonstrate capacity for any of the “five C’s of historical thinking“?

It’s a tricky question. Take context, for example. In their “five C’s” essay, Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke observe that

Imaginative play is what makes context, arguably the easiest, yet also, paradoxically, the most difficult of the five C’s to teach. Elementary school assignments that require students to research and wear medieval European clothes or build a California mission from sugar cubes both strive to teach context. The problem with such assignments is that they often blur the lines between reality and make-believe. The picturesque often trumps more banal or more disturbing truths.

And I’m not sure that I’ve made much headway in conveying contingency (“the most difficult of the C’s”) or complexity. Given our visits to Gettysburg and our temporary residence in the South, “Why did the Civil War happen?” has been a common question. I’ve tended to say that it was primarily about slavery and leave it at that. But then they noticed the panels at the Gettysburg visitor center counting how many soldiers each state contributed to the war: “Daddy, why did Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri have people fighting on both sides?” Um…

But the other two “Cs” are well within reach of our six-year olds. I’ll save change over time for #6 below, but causation is right up the alley of kids who love to take things part and put them together. I quickly realized that the single most helpful question I can ever ask at these museums and sites is one familiar from other contexts: “How do things work?” Or, “Why would people do ______ in the past?”

This works especially well at the Oliver Kelley Farm, which recreates a miniature economy that was largely self-sufficient but also tied in to larger markets. For example, we came across a cart that had wheels with no rubber or metal. “Lena and Isaiah, why do you think they made the wheels out of wood?” It took about five seconds for their eyes to turn to the forest separating the farm from the Mississippi River.

And that led right into this: “Isaiah and Lena, why do you think they lived so close to the river?” We talked about irrigation, but also that grain from farms like Oliver Kelley’s could be taken down the river to… yep, the flour mills in Minneapolis. (The Mill City Museum has a model that lets kids experiment with ground- and river-based transportation to get grain from the country to a mill in the city.)

And they could at least speculate about why Europeans like our German and Swedish ancestors crossed an ocean to settle farms like Kelley’s, or the sod house in the History Center. That points not only to a dawning awareness of causality, but to one last, especially meaningful realization…

6. Children are capable of historical empathy.

The relative absence of change over time — what we might call historical continuity — seems to come naturally to children. At the MN History Center, Isaiah and Lena enjoy an exhibit that recreates a small home on the East Side of St. Paul, with each room evoking a different era and a different ethnic group. Their favorite space is the backyard, where games from the childhood of my parents are instantly recognizable to their grandchildren.

Their next favorite part of the house is the post-WWII bedroom: they can put oversized coins in a giant piggy bank. Each coin represents the price at the time for ordinary household items. Money doesn’t play a big role in the world of a six-year old, but they have some sense that the numbers are oddly low — that the items are familiar, but their cost has changed significantly over time.

More importantly, children seem capable of historical empathy for people who inhabited a time quite unlike their own. Lena especially wants to reflect on what technological, economic, and other types of change mean for how people perceive and experience the world. Back to the Kelley Farm, where we had spent a lot of time thinking about all the tasks that go into a farm family’s day:

“Lena, what was your least favorite part of the farm?”

“I didn’t like the sheep… but they needed them to make clothes.”

“How do you think your life is different because you’re not growing up on a farm?”

“We don’t need to do that much work.”

Then a couple of weeks later, she took a step closer toward an imaginative understanding of the past as a “foreign country” when she told me, “Dad, history was hard.”

Updated from an earlier version published last year at The Pietist Schoolman