Last time I posted about the New Testament passages describing the anointing of Jesus. Here, I will explore the implications for approaches to Scripture, literalist and otherwise.

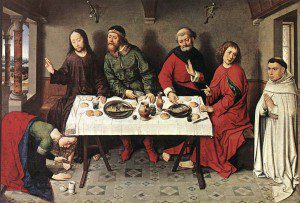

Each of the four gospels has a scene in which a woman uses costly oil to anoint Jesus, with the suggestion that this is in preparation for his imminent death and burial. The passages in question can be found at

Mark 14.3-9 Matthew 26.6-13 Luke 7.36-50 John 12.1-8

This is one of the rare examples in the gospels (outside the final accounts of Jesus’s death and resurrection) where we have a single episode described by all four evangelists in ways that allow us to trace how they are treated in the individual accounts. The fact that the same event appears in all four gospels suggests that it was seen as critical to understanding Jesus’s story, even if actual interpretations varied in detail. Early Christians knew that something very significant had happened at Bethany, if they could not agree about exactly what that was. As Ignatius wrote in the early second century, “the Lord received ointment on His head, that He might breathe incorruption upon the Church” (Ephesians 17)

In 1983, feminist theologian Elizabeth Schüssler-Fiorenza published the important book In Memory of Her. Whatever the book’s other virtues, the title alone makes a wonderful point. In both Mark and Matthew, Jesus tells his disciples not to criticize the woman because her act is so critically important: “Truly I tell you, wherever the gospel is preached throughout the world, what she has done will also be told, in memory of her.” Yet despite those potent words, none of the gospels except John actually gives her a personal name. For Schüssler-Fiorenza, this is a classic example of writing women out of the early Christian story, and she may be correct. But she is certainly right to stress the importance of the passage. On what other occasion did Jesus end a parable or miracle story with such a weighty prophecy about its lasting significance?

The four accounts are worth reading carefully, for detailed comparison. Although the passages have much in common, they differ substantially in detail. In the earliest account to be recorded, Mark says simply that a woman broke a jar of the ointment in order to anoint Jesus’s head. Matthew agrees, but Luke tells a much more dramatic story, in which the woman anoints Jesus’s feet and washes them with her hair. John follows the same account. Mark says that some of those present objected to the waste, Matthew says it was the disciples who got angry, Luke says it was Judas who objected. Luke says that a Pharisee present was disturbed not at the act, but by the person responsible, who was a sinful woman. All except Luke say the incident occurred at Bethany, while Luke gives no location. Each cites a different host or house-owner for the dinner. Three of the gospels suggest that the anointing woman was an outsider or passer by, while John says the anointer was Mary, who owned the house in which the dinner was being held.

The four accounts all differ substantially in the nature of the act and its consequences, what was said to Jesus and what he replied. Each uses the story to make a specific theological point.

The early church knew a story in which a woman anointed Jesus prior to his death, and that act was seen as having a special prophetic quality. Arguably, the woman in question was a prophet performing a very loaded symbolic deed. The story acquired other meanings and characteristics as it spread and was transmitted, with Mark’s as the simplest version, and John’s as much the most complex and elaborate. (As stories of any kind evolve, it is usually the later manifestations that are most prolific in minor characters, and most specific in giving them names).

Having said that, the biggest outlier in the group is Luke, who retains the core of the story while detaching it from its critical place as the prelude to Jesus’s crucifixion and death, a significance that is quite clear in Mark. In this instance, as in so many others, it is John who – for all the other additions and expansions – closely retains the original spirit and intent of the passage.

Luke does, though, acknowledge a special significance for Bethany, as the site of Jesus’s Ascension (Luke 24).

Putting all this together, then, then, none of the stories is a precise transcription or record of a single event. Each recounts a core story, although with different ways of presentation, and distinct messages.

That conclusion seems hard to avoid. You could, I suppose, claim that the different passages are describing separate events at multiple times, perhaps featuring different women, and each episode had a different quality or purpose. To me, that seems vastly less likely than the interpretation I suggested earlier, namely that the stories as we have them are variants on a single theme. That comment applies to versions as radically distinct as those found in Mark, Luke and John.

I am not sure how far we can properly use negative evidence in these matters. Mark, though, writing around 70, clearly does not know the “feet dried by hair” motif, nor does Matthew. You could propose that both authors knew it but choose not to mention it, but that is surely improbable. Assuming that we are in fact describing the same incident, the same anointing, that component only appears in Luke’s account, written in the 90s, and in John, not long afterwards. Obviously such a detail is not mentioned in any earlier Christian literature, for instance the epistles, which show so little interest in details of Jesus’s earthly career.

Can we propose, then, that “feet dried by hair” only appeared as a literary theme at some point during the 70s or 80s? The idea could of course have been circulating long before in a different context but only now attached to the key anointing scene. But the whole story does reinforce the impression that the last quarter of the first century – forty or fifty years after Jesus’s own time – was a period of extraordinary literary creativity within Christian communities.

A literalist might read my comments here as disrespectful or skeptical, which they certainly are not meant to be. The incidental details to which I am referring are the common repertoire of story-tellers through the centuries, and they do not detract for an instant from the historicity of the particular text. It is rather like reading more recent accounts that disagreed about whether a character in an incident was wearing a red or a green shirt – or whether indeed Napoleon’s entry into Moscow was on a black or a white horse. It honestly doesn’t matter. Only from the crudest literalist view could someone say that “Aha, different parts of the Bible are in disagreement! So they must be false and invented.”

Yes, it’s a cliché, but as Emerson said, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.”