During World War II, nearly 12,000 Americans registered as conscientious objectors and joined the Civilian Public Service (CPS). Unwilling to take human life, they instead served their country by doing everything from fighting forest fires to serving as test subjects for medical experiments. Most came from historic peace churches: Mennonite, Brethren, or Quaker. But Christians from over 200 denominations participated in the CPS, including a Baptist from Stromsburg, Nebraska named Curtis Johnson.

I came across his story while researching the history of my employer, Bethel University. Throughout the war Bethel president Henry Wingblade and college dean Emery Johnson regularly corresponded with service members from the Swedish Baptist General Conference. Curtis Johnson had spent two years as a member of the reserve officer training corps (ROTC) at the University of Nebraska. But after receiving Emery Johnson’s letter in late 1943, he wrote back to explain that he had long since

resolved that so long as life lasts, I would not permit myself to be enrolled in such an organization whose sole purpose is that of forcing a brother man to concede to our collective will, under penalty of death at our hands. The practice of war is, to put it but mildly, no more than government-sanctioned mass murder; and of course, one that has as his sole guide (poorly tho he may follow it) the example and teaching of such a one as Christ, finds it difficult to reconcile these entirely opposite behaviors in his thinking.

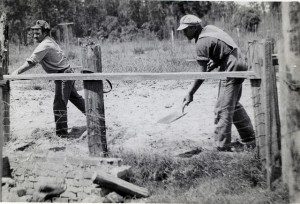

By that point, Curtis Johnson was at CPS Camp 27 in northern Florida, digging latrines for a project to combat the spread of hookworm. “They label us variously,” he told the Bethel dean, “conscientious objectors – pacifists – conchies – C.O.’s, religious objectors — and others that shouldn’t be printed. 1700 of us are in prison for the heinous crime of refusing to kill our fellow-man. 7000 are in camps such as this, serving out the duration in manual-labor, without pay of any kind, for the same reason.” After a long statement of Christian pacifism, he encouraged Emery to continue the conversation — “but I ask of you, back up everything you say by the example of teaching of Jesus, in whose Name I write, and seek to serve.”

Both that letter and the dean’s response a few weeks later are remarkable documents, all the more so because both Johnsons appealed so explicitly to their shared Baptist heritage. First, Curtis:

As I understand it, the Baptists have no creed save the Bible, or particularly as the New Testament portrays Christ’s plan for the life of an individual. You know, Mr. Johnson, Christ did set a tremendously difficult course for his followers to take. Suppose He were here now, walking along with you and me, suggesting to us a course of action in days such as these. Truthfully, can you conceive of Him giving His o.k. to your taking the life of some man, perhaps a German or a Japanese, some man that He died to save? Can you conceive of Him along side you in an airplane, dropping tons of explosive on helpless women and children, even tho your intention is to hit only munitions plants? Would He man the trigger on them occasionally for you, and show you how to do it more accurately? Did you ever try to imagine Commando Jesus Christ, private, first class, armed with every sort of knife, or club, or revolver, violently bringing the Kingdom of God here to men, and forcibly making them believe in Him as the all-powerful by physical process and military might?

…Perhaps I have a different version of the Bible than you have, but somehow, I don’t find anything like that picture of Christ in, for instance, the 5th, 6th, and 7th chapters of Matthew.

Indeed, nine years earlier his denomination had resolved that “War in light of the gospel of Jesus Christ and of human experience is a matter of hell.” Delegates to that meeting were convinced that “all Christians should absolutely refuse to take up arms against fellow men…”

But such attitudes were hard to find among Swedish Baptists after Pearl Harbor. And Curtis Johnson could hardly have picked a less sympathetic correspondent than Bethel’s dean. A few months later Emery Johnson complained to an alumnus serving in the Army Air Force that too many Bethel students were entering the school’s seminary as a way of dodging the draft: “We have among us very many Christian softies…”

But much as he disagreed with Curtis’s utter rejection of war, Emery nonetheless affirmed his freedom to come to that conclusion — and hinted that the war was being fought to preserve that Baptist distinctive:

The Baptists have always maintained that freedom of conscience is fundamental, and have insisted that man be allowed to make his own interpretation of the Master’s teachings under the leadership of the Spirit. Baptists have always insisted that church and state be separated. Baptists continue to hold these convictions and are always ready to fight to maintain these fundamental concepts.

* * * * *

What makes the exchange all the more interesting is that the first Swedish Baptist historians interpreted their movement as an outgrowth of Anabaptism. The first English-language history of the Swedish Baptists in America (1933), by J. O. Backlund, said less about English and German Baptist origins than about Anabaptist reformers like Menno Simons, who “remained faithful to his calling and continued to preach the gospel, urging a high standard of Christian morality, and created the Mennonite brotherhood into his own likeness, characterized by mildness of spirit, purity of morals and peacefulness in relation to their fellow-men.”

(Writing in September 1940 for the magazine of a denomination that remained pro-neutrality right up until December 1941, Backlund contended that “war is in itself a deterrent to the Christian life and spirit. You cannot hate your fellowmen, and seek their death, without losing something valuable from your soul…. Christ’s Peace on Earth must sound incongruous amid falling air bombs and shattered human dwellings.”)

Seven years after the war, in his centennial history of the denomination, Bethel professor Adolf Olson lauded the Anabaptists of the 16th century as “peace loving, God fearing and industrious folk who, contrary to the common trend of the times, advocated religious liberty, separation of church and state, and a regenerate church according to the teachings of the New Testament.” He quoted Baptist historian H.C. Vedders’ claim that the Magisterial Reformation was “a perversion of the genuine movement… Two centuries were required before the fruits of a real Reformation could ripen for the gathering; and it was in America, not Germany, that the genuine Reformation culminated.”

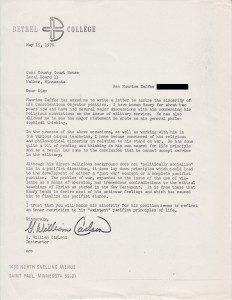

As the Baptist General Conference (“Swedish” left the name as WWII ended) started to outgrow its ethnic boundaries and identify more closely with the broader movement of neo-evangelicalism, such references to Anabaptist roots grew harder to locate — as did sympathy for Christian pacifism. Military recruiters were allowed on Bethel’s campus during the Vietnam War, and administrators even banned a table with “peace literature” during the school’s 1969 Founders’ Week. President Carl Lundquist did decline to host an ROTC chapter on campus, but more, he told a fellow Christian college president, “out of a desire to conserve our corporate energies than because of any philosophic commitment.”

But as Fletcher Warren found in his research for our Bethel at War project, some anti-war students rediscovered the denomination’s earlier reticence about participation in warfare. In 1970 the student newspaper reprinted a piece by seminary student Mark Olson that quoted the 1934 resolution against warfare and lamented how the BGC “seems afraid even to mention the issue, let alone admit its highly pacifistic past.” Two Bethel students, Dave Heikilla and Harold Conrad, convinced their draft boards to give them conscientious objector status in part because they could point to that history.

Others unknowingly echoed the argument of Curtis Johnson. Affirming their freedom as Baptists to interpret for themselves the Bible as their sole authority, they found the way of war incompatible with the example of Christ. “I was taught to obey the Lord all my life in Sunday School,” wrote Conrad in his application, “and Jesus taught only one way to treat an enemy: love him. I could not be a Christian and kill people because I would have to throw away the teachings of Christ.”