At the turn of the twentieth century, the United States was an exceptionally violent country, which really stood alone among advanced nations. I have been trying to account for this American Difference.

As an illustration, let me take a series of events that occurred in the late 1890s, and which actually happened about a block from where I am writing presently. The affair really has little wider political significance, but it is a perfect illustration of the kind of violence that was alarmingly commonplace at this time.

At the heart of the story was one William C. Brann (1855-1898), a journalist and newspaper editor who after long wanderings fetched up in Waco, Texas. He launched a series of fairly equal-opportunity attacks on various religious traditions and racial groups, but his special target was the Baptist stronghold of Baylor University. He focused on instances of sexual abuse and impropriety by leaders of Baylor’s academic community, acts that to him indicated massive hypocrisy. Brann’s paper, the Iconoclast, attracted national attention, with a reported hundred thousand readers. Baylor faculty and students loathed him, and on one occasion “Brann the Iconoclast” was kidnapped, beaten, and ordered to leave town. He didn’t. Matters grew far, far, worse when Brann’s enemies accused him of impugning the sexual morality of Baylor’s women students, of calling them Magdalens – prostitutes.

According to the Handbook of Texas presented by the Texas State Historical Association, events then escalated badly.

In November 1897 occurred a street gunfight between one of Brann’s supporters, McLennan county judge G. B. Gerald, and the pro-Baylor editor of the Waco Times-Herald, J. W. Harris, and his brother W. A. Harris. Both Harrises died, and the judge lost an arm. On April 1, 1898, on one of Waco’s main streets, Brann was shot in the back by a brooding supporter of Baylor University named Tom E. Davis. Before the editor died he was able to draw his own pistol and kill his assailant.

Wikipedia notes that

Engraved on Brann’s monument is the word TRUTH, and beneath it is a profile of Brann with a bullet hole in it.

Could anything vaguely like this have happened in contemporary Europe? In the fringe territories of the Balkans just maybe, but in a college town in Germany or France? Impossible. The police would have leapt in immediately, and that is a part of the main theme here, the relative weakness of the state mechanism within the US. Apart from the lack of effective policing, Americans commonly felt that civil means of obtaining justice were likely to be hopelessly partisan and biased, leaving them no alternative but to take the law into their own (armed) hands.

In case that sounds like I am describing the peculiar and transient circumstances of the “Wild West,” I am not. Very similar circumstances and attitudes applied for instance in the coalfields of Pennsylvania, the partisan rivalries of Kentucky or North Carolina, or the urban gang/political conflicts of the major cities.

Other obvious explanations for the violence fail badly. In itself, this Waco violence was not about racial tension, or the confrontation of labor and capital. Nor, incidentally, was it about gun culture. Guns were freely available even in England, and (contrary to myth) the police at this time had easy access to guns if and when they needed them. Ordinary people could have accumulated and used firearms, but they felt no need to.

The other main theme that emerges from the Waco battles is that of honor. Not to say that honor conflicts were unfamiliar in Europe, but they were restricted in terms of class, and formalized, especially through duels. The US democratized the duel.

You really can’t begin to understand US society through the nineteenth century without appreciating that potent and very widespread sense of honor and insult. For nineteenth century Americans, honor was the critical value underlying civilized society, and honor was the most cherished possession of a person, a family or a community. Honor was intimately linked to good reputation, which must be defended at all costs, and violence easily erupted in a society deeply sensitive to personal slights. Concepts of honor absolutely shaped the proper behavior expected of both sexes. The American obsession with honor and shame, insult and retaliation, already fascinated and horrified European visitors, and it is a centerpiece of Charles Dickens’s American Notes (1842). Defense of honor and family drove the country’s many Antebellum duels and personal feuds and vendettas, some of which amounted to minor wars.

I would argue that issues of honor go far towards explaining the Civil War. The South saw in Lincoln’s Republicans a massive threat to its survival, but also to the honor and reputation of its states, cities and families. Only armed force could correct the insult. Northerners enlisted in their thousands to avenge the insult to the national flag at Fort Sumter, and the violation of national honor. Both sides really did think they were fighting to defend their family and their womenfolk, for hearth and home. And the war of serial honor killing and vendetta only escalated from that point.

Critically, those ideas did not end with the war, but remained very much alive at the end of the century. They actually became far worse in an era of headlong economic growth, when the prizes at stake in such conflicts became so vastly more valuable. Look for instance at the huge land holdings at stake in the New Mexico faction fights: Republican Boss Thomas Catron owned some three million acres, placing him among the largest landowners ever in the history of the United States.

Meanwhile, perceived insults to womanhood were at the root of many of the lynchings that were so frequent in these years – not least the hideous murder of Jesse Washington that occurred in Waco itself, in 1916. About 1900, Rudyard Kipling made an interesting observation on the highly liberated state of American teen and adolescent girls, and their easy friendship and unchaperoned camaraderie with young men (From Sea to Sea, 1900). What a contrast to puritanical England! But those easy relationships were founded on the threat of swift and certain punishment if any of those boys took too many liberties, and violated codes of sexual honor:

Wherefore, in her own language, “she has a lovely time” with about two or three hundred boys who have sisters of their own, and a very accurate perception that if they were unworthy of their trust, a syndicate of other boys would probably pass them into a world where there is neither marrying nor giving in marriage.

In less literary terms, the offender would be shot or lynched.

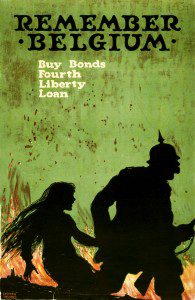

Such ideas of honor also help us understand the events of a century ago, that we are presently commemorating. The United States that entered the Great War on April 6, 1917, needed no lessons from European propagandists in doctrines of sacrifice and blood, honor and redemption. Not coincidentally, so many of that war’s propaganda images called American men to fight to protect or avenge threatened women, who variously represented France, Belgium, Serbia, or most commonly, Liberty herself. Often too, the symbolic woman was threatened with rape. American men must respond: manly honor demanded no less.

This 1918 image is in the public domain