A spectacular recent find in northern Africa throws new light on early church history, but at the same time it also points to the existence of a vast and forgotten Christian kingdom, and just how the faith – or indeed, any religion – fades and dies. The story makes for highly appropriate reading in the Easter season.

The find in question was made at al-Ghazali on the Nile, in northern Sudan. This “massive” burial ground was apparently associated with a Christian monastery, and many tombstones were inscribed in Greek or Coptic. Commonly, the prayers beseech that “that the soul will be taken care of and can rest on the bosom of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, or in the world of the Living.” The site itself stands near other remains marked by Christian rock art, which depict churches and saints.

Coptic monasteries were once very common, but the location of this particular one is so significant because it stands in an area where Christianity is not practiced today. That marks it off from Coptic Egypt to the north, and the lands of Ethiopia to the south east. Yet once upon a time, Christian kingdoms stretched all the way from the Mediterranean in the north to the Red Sea, from Egypt to Ethiopia, passing through the lands of Nubia. And al-Ghazali was clearly a monastic house of that lost Christian kingdom of Nubia, which is presently the missing ink in that Christian chain. It is one of the great examples of a region that was once largely Christian, but where the faith became extinct.

G. K. Chesterton once wrote of “The lands where Christians were… the little lands laid bare.” Yes, Christians were in Nubia, but these were anything but “little lands.” A rough estimate of the kingdom’s core territory would be rather larger than the size of Texas, or of France.

I described the story of Christian Nubia in my 2008 book The Lost History of Christianity, and I will adapt some of that material here.

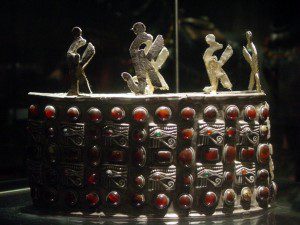

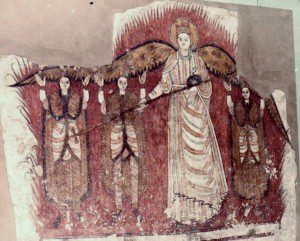

The Christian faith arrived here no later than the fourth century, and the great patriarch Athanasius consecrated a bishop in the region. Nubia survived as a Christian kingdom from the sixth century through the fifteenth, dominating the Nile between Khartoum and Aswan, and straddling the modern-day border of Egypt and Sudan. Nubia’s churches and cathedrals were decorated with rich murals in the best Byzantine style, showing their dark-skinned kings in royal robes. Its main cathedral at Faras was adorned with hundreds of paintings of kings and bishops, saints and biblical figures – images that lay forgotten under the sands until rediscovered in the 1960s.

Image in public domain, under Creative Commons Licence

This Christian state became a major player in African politics. In 745 its king invaded Egypt, with the goal of defending the patriarch of Alexandria:

And there were under the supremacy of Cyriacus, king of the Nubians, thirteen kings, ruling the kingdom and the country. He was the orthodox Ethiopian king of Al-Mukurrah; and he was entitled the Great King, upon whom the crown descended from Heaven; and he governed as far as the southern extremities of the earth.

By the 830s, the patriarch of Alexandria “appointed many bishops, and sent them to all places under the see of Saint Mark the evangelist, which include Africa and the Five Cities and Al-Kairuwân and Tripoli and the land of Egypt and Abyssinia and Nubia.”

The Nubians signed a treaty, a “pact,” with Islamic Egypt, which both sides respected for an impressive six centuries.

But Nubia’s fortunes deteriorated in the later Middle Ages, with the rise of the great Mamluk regime in Islamic Egypt. In 1275, the ferocious sultan Baybars conquered Christian Nubia, capturing its capital, Dongola. His forces sacked churches and forced the king, David, into exile. Repeated attacks weakened the state, while the growing crisis of the Egyptian church prevented Coptic authorities from supplying the bishops and priests essential to maintaining church life. By 1320, the royal church in Dongola had become a mosque, and around 1372, we hear of the ordination of the last Christian bishop.

Within a few decades, Nubia was both dechristianized and Arabized in language and culture, although a tiny Christian statelet lingered on until the late fifteenth century. At some unknown point – around 1500, perhaps? – some unknown church must have celebrated the land’s very last Good Friday liturgy, its final Easter service. The last Christians probably vanished around the time that Europe began its Reformation.

Sixteenth-century travelers were told that Nubia’s Christians

had received everything from “Rome” [i.e., Constantinople] and that it is a very long time since a bishop died whom they had received from Rome. Because of the wars of the Moors, they could not get another one, and they lost all their clergy and their Christianity and thus the Christian faith was forgotten.

The influx of Arabs and Nubians to Egypt and Sudan had contributed to the suppression of the Nubian identity following the collapse of the last Nubian kingdom around 1504. A major part of the modern Nubian population became totally Arabized and some claimed to be Arabs (Jaa’leen – the majority of Northern Sudanese – and some Donglawes in Sudan). A vast majority of the Nubian population is currently Muslim, and the Arabic language is their main medium of communication in addition to their indigenous old Nubian language.

In modern times, northern Sudan was devoutly Muslim, and its Christian past was largely forgotten. Just in the past few decades, at least two of its key monastic sites vanished under the newly constructed Lake Merowe.

The remains at al-Ghazali thus speak to a glorious but utterly lost history.

Or was the destruction as total as it seems? I will add one curious footnote. Nubians have always used the waters of the Nile for various ritual purposes, but one of the most persistent involves the washing of newborn babies, in what is commonly taken as a distant recollection of baptism. I quote Samia Ibrahim:

This ritual is similar to baptism performed by Christians for their newborn children. According to the book entitled ‘Discovery of Ancient Nuba History’ by Giovanni Fantini, these rituals still exist in Nuba areas in northern Sudan and Darfur in the west. These rituals testify to Nubians’ Christian past.

The priest of Two Martyrs Church, father Velothaos Faraj said a number of customs in Nuba districts are regarded as remnants of Christianity which existed in the Nubian regions between the sixth and the sixteenth centuries. These customs continued after the advent of Islam, including those that were associated with the river Nile. “The Nile is a sacred river to all Nuba population and they turn to it for renewed life,” he added.

The BBC radio series Heart and Soul recently broadcast an evocative podcast about the clandestine survival of baptism and other Christian practices among Nubians, at considerable risk to themselves.

Even now, even today, five hundred years after the national church formally ceased to exist.