In 1687, a measles epidemic swept away many of Boston’s children.

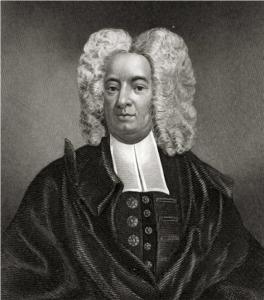

Cotton Mather preached on the subject on Christmas that year, delivering an afternoon sermon titled upon publication Right Thoughts in Sad Moments.

Mather’s message was standard puritan fare. God gives, and God takes away. Ultimately, God uses such afflictions for the benefit of his creation, sometimes to punish sin, always to remind us of our mortality and bring us to a more intimate knowledge of his Son and his Word.

At times, Mather sounds callous. “A Dead Child,” he observed, “is a sight no more surprizing than a broken Pitcher, or a blasted Flower.” Of course, Mather was correct. Perhaps a quarter of New England’s late-seventeenth-century children died before their tenth birthdays. Children and especially infants were, in the of the Massachusetts Bay poet Anne Bradstreet, “like as a bubble, or the brittle glass.”

Many New Englanders compared their children to flowers, and many of them died. Mather dedicated Right Thoughts to the wealthy Boston merchant Samuel Sewell, who along with his wife Hannah had already lost three of six children in their infancy (a seventh was stillborn).

Mather preached that such afflictions should cause Christians to repent of their sins that might have provoked the afflictions. Indeed, God may have punished them because they made their children idols and loved them more than they loved their Lord. “It is a blasted banned Soul that sets up a Creature in the Room,” Mather warned, “the Throne of the great God, that gives unto a Creature those Loves and those Cares which are due unto the great God alone.” Many ministers added that the bereaved should not grieve immoderately, as such behavior might further provoke God. These were hard words for many New England congregants.

How could Cotton Mather, and other ministers, preach such cruel words in the face of such human pain?

It is worth noting that Mather preached in the face of his own pain, because his first child, a daughter named Abigail, had died that very morning. “I am this day visited my self with the sudden Death of a dear and only Child,” Mather informed the congregation, and he added that he intended his words to quiet his own “tempestuous Rebellious Heart.”

There was perhaps not very much in puritan theology to give comfort to human beings in the face of death. One could not be certain whom God had elected to salvation. Especially when older children died, as Catherine Brekus so poignantly explored in her Sarah Osborn’s World, parents often agonized about their eternal fates.

The death of infants, though, revealed a point of what David Stannard termed “cognitive dissonance” in puritan thought. Although Calvin included infants within God’s decrees of salvation and damnation, at least late-seventeenth-century New Englanders could not bear to do so.

Cotton Mather allowed that “as to grown Children … the Soveraign disposals of God must be submitted unto.” Young children were different, however. Here, “the Fear of God will take away all matter of Scruple.” “Those dear Children,” he encouraged the congregation and himself, “are gone from your kind Arms into the sweet Bosom of Jesus.” In what became one of the very favorite verses of many Americans, he closed with the thought that “Of such is the Kingdom of Heaven.”

What to do in the face of affliction? Trust in God’s sovereignty, repent, and pray. Of course, there was nothing else that Cotton Mather or other grieving Bostonians could do. They protected their children as best they could from death, but they were mostly powerless.Their dead children would not rise like Jairus’s daughter, but they expected that Jesus would welcome their souls into heaven.

We Americans no longer live in a world in which a quarter of children die before their tenth birthdays, but we still live amid afflictions. And it’s not just or even primarily a question of mass shootings. Rather, according to the CDC, there are more than 10,000 homicides by firearms each year in the United States. Still, the mass shooting, like epidemics that swept away many children at once, are chilling. They remind us of life’s fragility and of the evil of which human beings are capable.

I am all for political action to reduce gun violence. In my mind, the risks of widespread gun access and ownership outweigh the risks of citizens being less able to defend themselves against either criminals or the possible rise of a police state. (There was a reason civil rights activists felt the need to arm themselves; states and their police forces are not always benign). It’s worth noting that in the case of the Texas church shooting, the proper enforcement of existing laws would have prevented the shooter from obtaining a weapon.

Guns are not a simple issue in the United States. Powerful weapons are so widespread that actually getting them out of the hands of potential criminals would be a very difficult task. The issue is political complicated in large part because Republican oppose most all gun-control measures and because Democrats in some cities have passed laws that brazenly violate the Second Amendment. I would prefer to repeal the Second Amendment rather than to pretend it does not exist. Since we live in a democracy, it is up to the advocates for gun-control measures to win the majorities that could enact them.

Over the past few years, it has become increasingly common for Democrats to mock or outright reject calls for prayer in the wake of shootings. “The thoughts and prayers of politicians are cruelly hollow if they are paired with continued legislative indifference,” stated Chris Murphy of Connecticut after the Las Vegas massacre. Rep. Ted Lieu walked out of a “moment of silence” out of his frustration with a lack of legislation action. Such criticisms clearly strike a nerve. House Speaker Paul Ryan, probably happy to whack Democrats for being anti-prayer, countered with the argument that “prayer works.” And it was particularly boorish for some to use the fact that the shooting took place in a church as proof that prayer does not work.

Admittedly, I have set up a false comparison here. In the face of a child’s unpreventable death, what can one do other than pray and seek to comfort the bereaved? By contrast, Americans could do much more to prevent gun violence. Moreover, “thoughts and prayers” make for an easy statement, and it’s hard to imagine that most politicians follow through. They probably are often empty and hollow words.

Why, though, would Christians and other believers not want to pray for and seek to comfort the afflicted? Just because a tragedy was preventable does not mean that individuals and communities should not turn to God in its wake.

“As soon as ever any Affliction befalls us,” Cotton Mather preached, “the First thing we do, should be to fall down upon our knees, to cry mightily unto the Lord that his Grace may be Sufficient for us.” Good advice.