I’ve spent most of my fall worshipping with a congregation other than my own, a Baptist church where I was teaching a six-week adult course on the Reformations. It happens to be popular with Bethel faculty and staff, including our president. Jay and I were in a meeting together the day after my class started, and he told me, “You’re the first person in years I’ve seen use a hymnal.”

Now, such books are widely available in his church’s pew racks, but they’re almost never used — even at the 9am “traditional” service. Though we sang at least three hymns each Sunday, worshippers read lyrics projected onto two enormous screens.

Inevitably, the technology failed one morning and the worship leader (with a smile, I thought) instructed us to “pull out the hymnals.”

But normally, the projectors work. So why do I insist on squinting at a hymnal when the words are glowing in front of me in mammoth electronic type?

First, holding and reading a hymnal reminds me that Christians are a people of the book, whose religious beliefs, imagination, and behavior have been and will be shaped by texts. Of course, I can see exactly the same words on a screen, but they feel less ephemeral and more serious when I see them rendered as black ink on white paper.

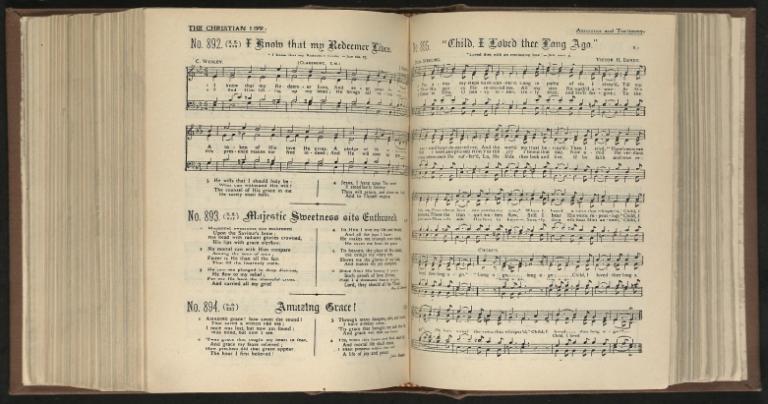

When bound in a book, those texts seem to have more heft. Literally, and figuratively. For reading lyrics out of a hymnal also reminds me that those words are part of an ancient tradition. I love seeing the dates of composition for texts and tunes, all the more so when the hymn we’re singing is side-by-side with a much older or much younger counterpart on a similar theme.

I suppose that you could put the same information on a screen… but it seldom happens. Nor, for that matter, do such slides tend to include the names of the people who authored the tune and text (and, often, translation), or the biblical verses that inspired them. Projected on a screen, hymns seem much like the stock images that illustrate sermons: anonymous and mass-produced. Hymnals remind me that God has spoken in many and various ways through women and men who were faithful to their vocations, dedicated to their crafts, and inspired to write words by their encounters with the Word.

Again, it’s conceivable that all that information could be included on a projected slide. But that would still leave the chief reason that I use hymnals:

I love to sing in harmony.

Just yesterday I was reminded that one of my favorite members of the great cloud of witnesses scorned multi-part singing:

Because it is bound wholly to the Word, the singing of the congregation, especially of the family congregation, is essentially singing in unison. Here words and music combine in a unique way. The soaring tone of unison singing finds its sole and essential support in the words that are sung and therefore does not need the musical support of other voices.

…The purity of unison singing, unaffected by alien motives of musical techniques, the clarity, unspoiled by the attempt to give musical art an autonomy of its own apart from the words, the simplicity and frugality, the humaneness and warmth of this way of singing is the essence of all congregational singing…. This is singing from the heart, singing to the Lord, singing the Word: this is singing in unity…. (Life Together, pp. 59-60)

But even someone so sainted as Dietrich Bonhoeffer was wrong about some things.

First, as venerable as his preferred mode is in the musical history of the Church, harmony singing has its own rich tradition. John Calvin may have forbidden it (and instrumental accompaniment) in his quest for “simple and pure singing of the divine praises,” but Luther’s first hymnbook (Neue geistliche Gesänge, 1523) had four parts. Andrew Wilson-Dickson notes that, unlikely as it may sound to us, “in Luther’s time students would gather round a table to sing in harmony from part-books just for amusement” (The Story of Christian Music, p. 62 — the preceding Calvin quotation comes from p. 65). And while few 18th century Anglicans were initially skilled enough to sing the works of Isaac Watts in harmony, things changed under the influence of Charles and John Wesley. Their renewal movement not only insisted on making hymnody more accessible to laypeople, but Methodists invested time in teaching each other to sing. As a result, it became more and more common to hear antiphonal and harmony singing in Methodist chapels, whether or not there was instrumental accompaniment.

The story continues into the 19th and 20th centuries. Even without much training, the “shape note” singers of the Sacred Harp tradition threw themselves into a gloriously loud, rough-hewn harmony. And it beggars belief that Bonhoeffer — so famously taken with the gospel music he encountered at Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem — would have believed that so polyphonous a musical tradition as that of African American Christianity did not count as “singing from the heart, singing to the Lord, singing the Word.”

But much as they remind me of such history, what matters most to me is that reading those harmony parts out of a hymnal helps sustain two dimensions of Christianity that Protestants have tended to neglect:

Beauty

Beauty as a theological theme has not exactly been an emphasis of traditions descended from the Reformation, more accustomed to suspicion of lovely things and those who create them. But fortunately Lutheranism retained enough of Luther’s appreciation for the rich culture of the Late Middle Ages to yield hymns like Philipp Nicolai’s “Wachet Auf” and to inspire composers like J.S. Bach, who added one of his complex harmonizations to enrich Nicolai’s soaring melody. Two centuries later, Scandinavian Lutheranism spun off the Midwestern choral tradition of F. Melius Christiansen et al., which has been my chief instructor in multi-part singing.

I know such adornment isn’t strictly necessary. But while a tune like Rowland Prichard’s “Hyfrydol” is perfectly fine sung as a solo, adding the moving harmony parts to a text like “Savior, While My Heart Is Tender” can soften the hardest heart. Back to back in the hymnal I grew up singing, we tenors are called to add some achingly lovely phrases to two heartbreaking hymns about the Crucifixion: Lowell Mason’s harmonization of Watts’ “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross” (whose final four bars nearly make me cry every time I sing them) and the traditional setting of the American folk hymn “Were You There?”

Of course, beauty for its own sake doesn’t defeat Bonhoeffer’s argument. In one of his funniest songs, Steve Martin claims that “Atheists Don’t Have No Songs,” but if they did, I’m sure they could have lovely four-part arrangements. Still, beauty can testify to the creative and redeeming power of the Word, and for a few verses lift our world-weary hearts and spirits heaven-ward.

Unity

Here again, there is clear value in unison singing, as Bonhoeffer eloquently, if forcefully argued in Life Together. Unison singing can embody the unity of the Church for which Jesus prayed in John 17 or Paul advocated in most of his epistles (e.g., Eph 4:1-6).

But so too can singing several parts in a congregation. Harmony, after all, is a pretty good aspiration for the many parts that compose the Body of Christ (cf. Rom 12:16). Let me hesitantly suggest that “unisonality” pushes us towards viewing unity as “uniformity.” Whereas living — and singing — in harmony recognizes that differences exist.

Some are differences of degree of power or status, so Paul tells the Romans not to be proud and the Ephesians to be humble. Harmony singing likewise trains us to subordinate our own abilities (however well trained) to the good of all. Beautiful as some tenor lines are, many of them aren’t all that challenging; however, even three or four droning notes add depth to what the melody and other harmony lines are doing.

Then harmonious hymnody also helps us to recognize that the Body of Christ consists of many parts with different talents and callings, all of which are important. Just as some are called to be teachers and others healers and are given gifts commensurate with those vocations, is it truly vain to believe that some are called and gifted to sing different parts in worship?

Whatever the dangers of “vanity and bad taste” that might ensue from multi-part congregational singing gone awry, far worse are the dangers of worship in which God-given gifts are left idle, or even scorned. (To say nothing of worship in which those who “lead” worship become performers while the rest of the congregation becomes an audience.) In my experience, at least, a congregation singing in harmony — evenespecially when not done perfectly — becomes a visible sign of the invisible grace that unites the different parts of the Body into one Church.

And that’s awfully hard to accomplish without a hymnal in your hands.

The second half of this post updates something I’d previously written at The Pietist Schoolman.