I’m pleased to introduce this guest post by Lisa Weaver Swartz. She earned a Ph.D. in sociology from the University of Notre Dame in 2017. Her dissertation focused on gender narratives and practices at two evangelical seminaries: Southern Baptist Theological Seminary and Asbury Theological Seminary.

***

Madeline L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time was first published in 1962. This date, of course, placed it amidst fears of communism in the Cold War era. But its publication also coincides with another historical turning point. Just months after its release, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique also hit the shelves. In fact, L’Engle and Friedan shared more than publication dates. The two women were also classmates at Smith College where they worked together on a campus publication called Smith College Monthly.

Both emerged from comfortable 1950s suburbia as educated, ambitious women in a world not built for their success. Friedan took on this world with an activist posture, boldly critiquing patriarchal social arrangements. Her work, of course, helped spark the second-wave feminist movement.

L’Engle took a subtler feminist path. Her literary career produced not only A Wrinkle in Time, but also a delightful array of both fiction and nonfiction. The undercurrent of her work was not liberal feminism but L’Engle’s Christian faith. She sprinkled her fiction with references to the Bible and Christianity. Later in her career, she wrote Walking on Water, a consideration of the relationship between art and spirituality and The Genesis Trilogy, an expanded meditation drawn from the biblical book of Genesis. She does not appear to have claimed a feminist label, but L’Engle’s granddaughter and biographer Lena Roy recalls her pride at being a “trailblazing woman.”

L’Engle did indeed blaze new trails. Whether she aligned herself with the feminism of her day or not, L’Engle’s plot twists and character choices reflect some of contemporary feminism’s strongest claims.

Restoring Women’s Standpoint

First, L’Engle constructed A Wrinkle in Time around women’s standpoint. Long before notions of positionality and situated knowledge became important in intellectual discourse, L’Engle presented a strong, evocative narrative with women at the center. Wrinkle is a wild tale of science and power and terror and wisdom all focalized through the standpoint of Meg, a plain self-conscious adolescent girl. Although the story is narrated in the third person, it is clearly derived from Meg’s own experiences and bounded by her knowledge.

L’Engle does not only preserve women’s standpoint. She prioritizes it. At the story’s climax, Meg is very much on her own, alone with her flaws and limitations. She is the only one who can save her family from the clutches of evil. It is not as if L’Engle has written herself into a corner. In fact, the book is full of promising male characters. There is Meg’s father, a brilliant scientist. There is Charles Wallace, her precocious little brother. Meg’s handsome classmate, Calvin, is also along for the ride. But none of these male characters hold the solution. Even Charles Wallace, who understands the seriousness of the situation much earlier than his sister, seems to grasp the importance of the ordinary, awkward Meg taking the lead. L’Engle narrates Meg as the solution to evil—not despite her female standpoint, but because of it.

In the decades that followed A Wrinkle in Time, feminist theorists gave language to L’Engle’s literary twists. Standpoint feminists like Patricia Hill Collins and Dorothy Smith argue that knowledge derived from the male experience is incomplete. They suggest that because women’s lives and roles in almost all societies are significantly different from men’s, women hold a different type of knowledge. Similarly, Donna Haraway argues for what she calls situated knowledges. It is important, these scholars tell us, to recognize that different kinds of knowledge come from different places. In other words, our experiences and positions in society constrain what we can know. For Haraway, knowledge is legitimate when it can be located somewhere and called into account. Meg’s knowledge, both she and the reader discover, is located not only in her association with men. It is formed in her own experience, in her own relationships, and her love for her family.

Choosing Love

Sandra Harding extends this discussion of women’s standpoint. She contends that androcentric epistemology offers a dispassionate, removed, impartial, and scientific approach to knowledge. By contrast, women’s experience very often arises from nurture and human relationships. Women hold and guard life. They humanize from the margins. Being a woman, Harding says, means being attuned to emotion and interested in human welfare. This knowledge often makes women more aware of the needs of the oppressed and less interested in maintaining the status quo.

This too is apparent in the Wrinkle narrative. Meg initially assumes that her vulnerability is a weakness, that her deep love for her family is something to be overcome. But at the climax of the narrative, when she is deprived of all other resources and support, Meg recognizes that love—not brute force, not weapons, not intellect—is the only power that can save her brother and restore her family. Love itself becomes the final solution.

This too is apparent in the Wrinkle narrative. Meg initially assumes that her vulnerability is a weakness, that her deep love for her family is something to be overcome. But at the climax of the narrative, when she is deprived of all other resources and support, Meg recognizes that love—not brute force, not weapons, not intellect—is the only power that can save her brother and restore her family. Love itself becomes the final solution.

A full thirty years later, bell hooks issued a strikingly similar call for love as a tool of liberation. “Without love,” hooks writes, “our efforts to liberate ourselves and our world community from oppression and exploitation are doomed. As long as we refuse to address fully the place of love in struggles for liberation we will not be able to create a culture of conversion where there is a mass turning away from an ethic of domination.”

Hooks’s call, and L’Engle’s narrative framing of it, also recall much earlier feminist rhetoric. In their fight for the right to vote, for example, many of the earliest American feminists in the nineteenth century argued that women’s voices should be active in public discourse precisely because they were different from men’s. They worried that men would get so caught up in business interests and military exploits that they would forget to be compassionate and kind. History has not proven them wrong.

Recovering the Feminine

Finally, A Wrinkle in Time also celebrates diverse expressions of feminine identity. This stood in contrast to Friedan and other second-wavers who downplayed femininity and sometimes dismissed domesticity and even expressions of beauty.

L’Engle defies both of these impulses. As if anticipating the diverse expressions of feminism that would follow, she introduces Mrs. Who, Mrs. Which, and Mrs. Whatsit. The colorful Mrs. Who seems to be something of a mystic, energized by the voices of past wisdom. Mrs. Which is larger than life and more than a little intimidating. Mrs. Whatsit is scattered and idiosyncratic. This variation, which seems not at all troubling to the trio themselves, contrasts with the uniform feminism of the 1960s. It leaves space for women in the decades to follow like Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, who confidently identified herself in 2014 as a “Happy African Feminist Who Does Not Hate Men and Who Likes to Wear Lip Gloss and High Heels for Herself and Not For Men.”

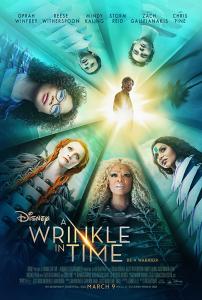

This expanded vision of feminism is especially apparent in Disney’s new movie version of L’Engle’s novel. Director Ava DuVernay dresses her characters in spectacular costumes. When Meg, and the audience, first meet Mrs. Who, she is surrounded by books and flowers and beautifully colored cloth that she appears to be crafting into a quilt—an art form that has been passed down by women (and largely limited to women) throughout history. All three Mrs. Ws wear vibrantly colored, elaborately styled clothing. And there is glitter—on their eyelids and foreheads and in their lipstick. These characters are not only women, they are undeniably feminine. They are magnificent creatures who simultaneously embody beauty, wisdom, and power.

This expanded vision of feminism is especially apparent in Disney’s new movie version of L’Engle’s novel. Director Ava DuVernay dresses her characters in spectacular costumes. When Meg, and the audience, first meet Mrs. Who, she is surrounded by books and flowers and beautifully colored cloth that she appears to be crafting into a quilt—an art form that has been passed down by women (and largely limited to women) throughout history. All three Mrs. Ws wear vibrantly colored, elaborately styled clothing. And there is glitter—on their eyelids and foreheads and in their lipstick. These characters are not only women, they are undeniably feminine. They are magnificent creatures who simultaneously embody beauty, wisdom, and power.

This navigation of feminine authority extends beyond physical appearance. As the audience watches, the novice Mrs. Whatsit experiments with her own power. When Meg struggles through her first “tessering” experience and lands in an unconscious heap on the ground, Mrs. Whatsit gently nudges her with a foot. She is immediately rebuked by the seasoned Mrs. Who. “Whatsit. We don’t kick people.” This feminine is not a new version of the masculine. It is decidedly different. Even subtle dehumanization—like a gentle kick—is not to be tolerated.

***

In many ways, then, L’Engle’s Wrinkle stands the test of time better than Friedan’s Feminine Mystique. L’Engle may not have joined her college classmate in the political fight for gender equality, but she did pursue a later iteration of the feminist movement. In a bit of literary time-travelling of its own, A Wrinkle in Time points forward to the voices of Sandra Harding, Patricia Hill Collins, and bell hooks.

Indeed, L’Engle’s insistence on merging power with love—and on prioritizing women’s knowledge—is remarkable given that she did not have the benefit of discursive categories like standpoint epistemology and critical feminism. It does seem clear, however, that L’Engle operated in a Christian orbit that directed her away from aggression, adversarial posturing, and disembodied objectivity, and toward traditionally feminine themes of love, redemption, and creative salvation. Though she did not overtly situate her work within feminist conversations, L’Engle nonetheless points toward a vast spectrum of feminisms, some of which resonate deeply with Christian faith.