Only out of the past can you make the future,” says a character in Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men. And yet some pasts are dreadfully dark and tangled, and how one wrings a future from them is anyone’s guess.

This thought gnawed at me during a recent trip to Bosnia-Herzegovina and other Balkan states. I had gone in search of interviewees for a research project on interreligious dialogue. I wanted to talk with people removed from the tired multiculturalism of the West, people who had attempted dialogue in truly challenging circumstances; I wanted to make sense, theologically, of their experience amid the darkness of their recent past.

Interviewees, I found. Theological sense remains elusive.

Geography does not explain everything in history, only a lot of things. Students of Europe know that the region of the Balkans once had the misfortune to find itself at the crossroads of three world powers: the Ottoman Empire; the Austro-Hungarian Empire; and Russia’s Tsardom, whose power was projected through its client nation, Serbia. Although the religious dimension in these three geopolitical powers is often elided, the fact is that all three derived legitimacy through spiritually sanctioned narratives about their imperial identity and historical mission. Austria-Hungary remembered itself as the legatee of the Holy Roman Empire, which traced its roots to Charlemagne, protector of Western Christendom. Moscow saw itself as the “third Rome” after the fall of Constantinople in 1453—and as such, the guardian of Eastern Orthodox Christianity. And the Ottoman Empire, of course, was the last great Islamic caliphate, the scourge of Europe in the days of Suleiman the Magnificent (1494–1566) and the self-proclaimed protector of the worldwide Muslim community.

In other words, it is not just imperial interests in the abstract that have clashed in the Balkans, but rival narratives about the proper constitution of religious truth and its implications for political order. Over the centuries, one or another power frequently managed to impose a Hobbesian order in the region, or achieve a balance of power with the others which allowed for peaceful coexistence. The not-infrequent periods of exceptions to this rule condemned the region to cycles of revenge and violence involving the three main regional faiths, ethnically manifested in Serbs, Croats, Turks, Bulgarians, Greeks, Albanians, and more. Not without reason do most Western languages possess some variant of the verb “balkanize.”

The Nobel Prize–winning writer Ivo Andrić vividly captures these violent cycles in his 1945 novel, The Bridge on the Drina. A favorite Balkan method of suppressing dissent, employed by Turks and then others, was public impalement. Andrić offers what is surely the most graphic depiction in world literature of this horrific cruelty, in which the executioner pushed a sharpened wooden pole up the anus of the victim until it emerged in the shoulder area. Sadly, impalement is an apt symbol of the region’s past, bespeaking the violence that all too often prevailed between times of fragile peace among rival ethnic groups. (The literary character we know as Count Dracula, it might be remembered, is derived from the medieval Balkan lord, Vlad the Impaler.)

Nationalism in the nineteenth century presaged the end of the three Empires, all of which perished due to the furies of World War I, which of course began with an assassination in Sarajevo. What had been dubbed “the Eastern Question” had long baffled Western statesmen, and the war’s end gave them a chance to meddle in the Balkans directly. When the dust had settled, a multiethnic concoction known as “Yugoslavia” appeared, existing first as a constitutional monarchy under the Serbian royal house and then, after World War II, as a federal socialist republic. A political curiosity during the Cold War, standing aloof from Moscow while opposing Washington, the “nonaligned” Yugoslav state survived largely due to the ability of strongman Marshal Tito to suppress conflict under his cult of personality (still on display today at the mausoleum museum dedicated to him in Belgrade). When Sarajevo hosted the winter Olympics in 1984, the world beheld a peaceful country, destined to last; one commentator in fact noted the “powerful irony” of World War I having started in such a benign city.

The Yugoslav wars of the 1990s shattered this delusion. Begun before 9/11 consigned the Balkans to peripheral interest in Western consciousness, these wars dominated the news of the day, bringing such names as Franjo Tudjman, Alija Izetbegović, Slobodan Milošević, Radovan Karadžić, and Ratko Mladić to the fore. A graduate student in history at the time, I struggled to understand the complexity of it all—and perhaps at some level dismissed it as the faraway feuds of those who hadn’t yet gotten wind that history, as Francis Fukuyama proclaimed, had already ended.

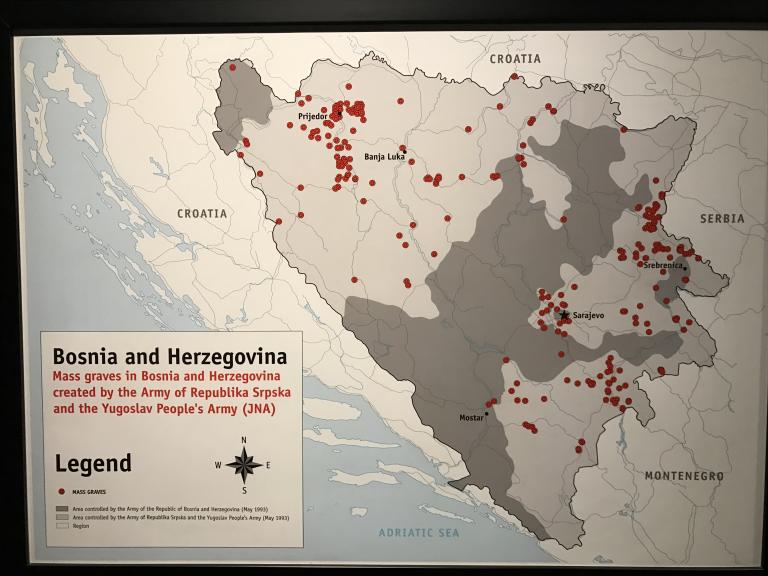

But history never ends; and one by one, amid bloodshed, battles, and “ethnic cleansing”—the conflicts’ addition to our vocabulary—the six socialist republics of Yugoslavia went their own way, leaving behind the present-day countries of Bosnia and Herzegovina (often shortened to just Bosnia), Croatia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Slovenia, and Serbia, as well as two autonomous provinces, Vojvodina and Kosovo—the latter eventually becoming its own state after wresting itself from Serbia’s grasp, with help from NATO muscle. In total, the conflicts of the 1990s produced an estimated 140,000 dead and some 4 million refugees . . .

***

One can read the entire article here It first appeared in the journal Commonweal (February 26, 2018) under the title, “After Genocide: Searching for Reconciliation in the Balkans.”