BYU student Tara Westover was suffering from a two-day earache that caused her to miss church. Then the earache turned into a constant sharp stab in the head. She developed a fever, and her vision got distorted to the point where it wasn’t safe to drive.

Her boyfriend asked what she had taken. “Lobelia,” she said. “And skullcap.” “I don’t think they’re working,” he said.” She replied, “They will. They take a few days.”

Later, the boyfriend popped open a bottle and gave her two red pills. “This is what people take for pain,” he said. “Not us,” Westover replied. “Mother always said that medical drugs are a special kind of poison, one that never leaves your body but rots you slowly from the inside for the rest of your life. She told me if I took a drug now, even if I didn’t have children for a decade, they would be deformed.”

But he filled a glass of water and set it in front of Tara. Then he gently pushed the pills forward until they touched her arm. “I picked one up. I’d never seen a pill up close before. It was small than I’d expected.”

She swallowed one, then the other. “Twenty minutes after I swallowed the red pills, the earache was gone. I couldn’t comprehend its absence. I spent the afternoon swinging my head from left to right, trying to jog the pain loose again.” The boyfriend watched in silence, undoubtedly finding her behavior strange, especially when she began to pull on her ear to test the limits of this “strange witchcraft” called Tylenol.

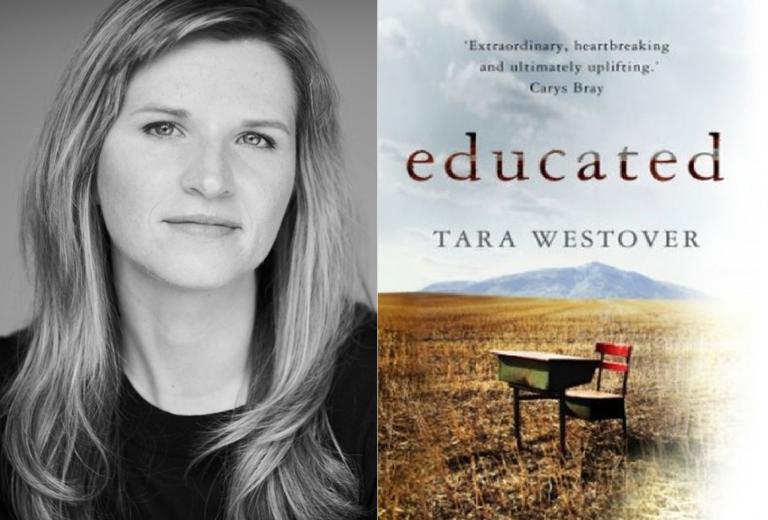

This episode from the fascinating memoir Educated illustrates Westover’s antiestablishment childhood in a fundamentalist Mormon family in Buck’s Peak, Idaho. Obsessed about Y2K, sympathetic toward the Weaver clan when the feds raided Ruby Ridge, worried that the public-school system would indoctrinate their children, the Westovers’ anti-medicine beliefs were just one plank in a much broader anti-establishment ideology. The family drilled for their own water so they would be less dependent on the government. They hoarded fruit in Mason jars. “There’s a family not far from here,” Dad said. “They’re freedom fighters. They wouldn’t let the Government brainwash their kids in them public schools, so the Feds came after them.” “We can’t help them, but we can help ourselves. When the Feds come to Buck’s Peak, we’ll be ready.”

This episode from the fascinating memoir Educated illustrates Westover’s antiestablishment childhood in a fundamentalist Mormon family in Buck’s Peak, Idaho. Obsessed about Y2K, sympathetic toward the Weaver clan when the feds raided Ruby Ridge, worried that the public-school system would indoctrinate their children, the Westovers’ anti-medicine beliefs were just one plank in a much broader anti-establishment ideology. The family drilled for their own water so they would be less dependent on the government. They hoarded fruit in Mason jars. “There’s a family not far from here,” Dad said. “They’re freedom fighters. They wouldn’t let the Government brainwash their kids in them public schools, so the Feds came after them.” “We can’t help them, but we can help ourselves. When the Feds come to Buck’s Peak, we’ll be ready.”

Seventeen years old when she set foot in a school classroom for the first time, Westover arrived at BYU not knowing about the Holocaust, the civil rights movement, the difference between North and South Korea. She was not “educated,” but she was smart and had learned how to learn. In fact, three out of the seven Westover children have gone on to earn a Ph.D., something that the family’s attorney used in a statement to defend the family’s homeschooling bona fides.

But college is not just about learning. It’s also about social adaptation, and Westover refused at first to adapt. She never used soap except when showering once a week. She did not wash her hands after using the bathroom. “Frivolous,” she said. “I didn’t pee on my hands.” Her roommates looked at her like she was a rabid dog.

If Westover’s weirdness alienated her from classmates at BYU, the family’s antiestablishment ideology definitely paid off financially. The lobelia, skullcap, frankincense, and other homeopathics her mother had begun selling out of her kitchen became a roaring success. Frankincense, derived from the resin of trees grown in the Middle East, was especially coveted by Christian conservatives for its ability to regenerate cells and for its biblical prominence. “The power of God on earth,” her father would exclaim. “That’s what these oils are: God’s pharmacy!”

Westover’s mother LaRee began to sell. Thousands of wives and mothers came to three-hour essential oils workshops held in local homes around Buck’s Peak. (Here’s a good example of a workshop: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0PgEW9lCCpk). She wrote and sold a book titled Butterfly Miracles with Essential Oils. Before too long, their company, Butterfly Express, began to eat into the profits of large corporate producers, and one offered to buy her out for $3 million. But that wasn’t the point. She was a true believer who wanted to proselytize the unconverted. LaRee, the matriarch of seven children and 32 grandchildren, only wanted money enough to buy food, fuel, and maybe a bomb shelter.

Observers have long noted a correlation between startups in the health industry and conservative religion. This New Yorker article explains that Utah has more multilevel-marketing companies per capita than any other state. In fact, direct sales are Utah’s second-biggest source of revenue, after tourism. Moreover, writes Rachel Monroe, “The Mormon Church also has a long-standing mistrust of federal oversight, which has made Utah a friendly home for businesses that operate outside medical norms. Attempts to regulate these industries are often portrayed as threats to individual freedom.” In Utah County, a hub of Utah’s alternative-health industry, 43 percent of kindergartners have not received their vaccinations.

How representative is the Westover family? Tara Westover is a careful scholar with strong training in history at BYU, Cambridge, and Harvard, so she’s careful to qualify the narrative (which is definitely a memoir, not a piece of scholarship). The Westovers do not represent the mainstream of the Latter-Day Saints. Indeed, they were on the margins of their local ward, and the father probably suffers from bipolar disorder. Nor does the family represent the essential oil industry. But is there in fact something about the dualism of patriarchal “pure religion” that lends itself toward an anti-establishment gospel of health? I would love to see how scholars of religion have tackled this subject. What does the hive mind recommend?