Some years ago, I wrote a book titled Jesus Wars, about the Christological controversies of the fifth century, focusing on the famous Councils of Ephesus (431) and Chalcedon (451). My recent travels in Italy have involved many encounters with that world of the fifth century, which is so critical for making later Christian life and thought, and especially art and culture. My next couple of blogposts describe these travels through the fifth century, which have stirred so many thoughts about Christian origins, and the position of culture in shaping faith. Putting these various churches and monuments together makes it possible to construct a stunningly comprehensive picture of the way Christians thought and believed, far beyond anything we can possibly derive from even the most skilled research in written evidence. We can see and touch a whole world of belief.

Much of what I will say concerns the awe-inspiring city of Ravenna, but let me begin here with key monuments of that era as they are found in Rome. My Jesus Wars bore the subtitle How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years, and so many of those figures – patriarchs and queens especially – have left their mark in Rome. For my purposes, two crucial churches stand out in particular, namely San Pietro in Vincoli, St. Peter in Chains, and the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

Much of what I will say concerns the awe-inspiring city of Ravenna, but let me begin here with key monuments of that era as they are found in Rome. My Jesus Wars bore the subtitle How Four Patriarchs, Three Queens, and Two Emperors Decided What Christians Would Believe for the Next 1,500 Years, and so many of those figures – patriarchs and queens especially – have left their mark in Rome. For my purposes, two crucial churches stand out in particular, namely San Pietro in Vincoli, St. Peter in Chains, and the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore.

San Pietro in Vincoli is overwhelmed with associations from that fifth century world, which I was thoroughly relishing, puzzled as to why so many other visitors were concentrating on a mere side altar. A quick glimpse gave the answer. This was the tomb of Julius II, which incorporates Michelangelo’s statue of the horned Moses, one of the most celebrated two or three works of Renaissance sculpture. That’s Rome: just blink, and you’ll miss the greatest treasures of world art.

What about the fifth century? This was a pivotal time in theology, and for the great churches and patriarchates. In 431, the Council of Ephesus approved and reinforced an exalted view of the Virgin Mary as Theotokos, Mother of God, and that was reflected in a new surge of Marian devotion. Among the main players in this theological-political complex were the Popes Sixtus III (432-440) and his very distinguished successor Leo the Great (440-461), one of the most influential of all Popes. Both Sixtus and Leo were major builders, especially of churches. Juvenal, Bishop of Jerusalem, was struggling to have his see recognized as a Patriarchate, which finally occurred in 451. Among secular rulers, the most significant tended to be royal women, queens and princesses.

I should also say something about Rome, and Italy. We know the famous date 410, when the Visigoths sacked Rome, and sometimes assume that this was in a sense “the fall of the Roman Empire,” at least in the West. Of course it was no such thing. Rome rebuilt after 410, and faced a new sack by the Vandals, in 455. In 476, the Western Empire ended only to the extent that Western authorities agreed to accept the authority of one united Roman Empire, based in New Rome, Constantinople. In the 440s (say), there was still a Western Emperor and a royal family. That Emperor in fact was Valentinian III, who ruled from 423 through 455, whose wife was the Empress Eudoxia.

The big difference from earlier eras was after 402, the Western emperors usually lived in Ravenna, near the Roman fleet’s base at Classis (Classe: classis just means a fleet). This mosaic actually portrays Ravenna as it appeared around 500, with its skyline dominated by palaces and churches, and with Classis named separately:

By default, the city of Rome itself was increasingly a Papal city, church territory, and it was being rebuilt accordingly.

To tie the story together a little, let me describe one of these royals, whose career no novelist would dare invent. This was the amazing Galla Placidia (c.390-450), daughter of the Emperor Theodosius I. Around the time of the sack in 410, she was carried off by the Visigoths, and married their king. When he died, she returned to Roman territory, and married a short lived Roman emperor, based in Ravenna. Their son was the long-ruling Valentinian III. Galla Placidia served as regent in his childhood, and remained for many years a power behind the throne. She was an active and militant supporter of papal and Chalcedonian Christianity. As we will see, she is associated with some of the most spectacular artistic glories of Ravenna, which rank among the greatest creations of Christian art in any period, not just the early church. When you visit Ravenna, you are very much in her presence, and her shadow.

Galla Placidia left a daughter, Justa Grata Honoria, whose own career was as spectacularly improbable as her own. Together with her lover, Honoria plotted to assassinate her brother Valentinian and take over the empire. When the conspiracy was revealed, she was sent to a convent, but the prospect of that lifestyle appalled her. Seeking an escape route, she turned to a new prospective lover with a solid record of achievement in public affairs: Attila the Hun. Honoria wrote to Attila, offering to marry him if he would free her, and in exchange she would give him title to rule the Western empire. Attila used the correspondence as an excuse to launch his invasion of Gaul, which he presented as an attempt to take his promised bride and dowry. That particular plot would scarcely carry conviction in a bad romance novel, and its only excuse is that it actually happened.

Galla Placidia left a daughter, Justa Grata Honoria, whose own career was as spectacularly improbable as her own. Together with her lover, Honoria plotted to assassinate her brother Valentinian and take over the empire. When the conspiracy was revealed, she was sent to a convent, but the prospect of that lifestyle appalled her. Seeking an escape route, she turned to a new prospective lover with a solid record of achievement in public affairs: Attila the Hun. Honoria wrote to Attila, offering to marry him if he would free her, and in exchange she would give him title to rule the Western empire. Attila used the correspondence as an excuse to launch his invasion of Gaul, which he presented as an attempt to take his promised bride and dowry. That particular plot would scarcely carry conviction in a bad romance novel, and its only excuse is that it actually happened.

Pushing the bounds of credibility further, Honoria was not the only imperial woman to invite an invasion of her own empire out of personal reasons and family grievance. Just three years after Honoria’s Hunnish flirtation, her example inspired her cousin Licinia Eudoxia to invite the Vandal king Gaiseric to attack Italy. He did so with gusto in the second sack of Rome (455).

It is sometimes not too easy to tell the difference between the Theodosian dynasty and the Borgias. Or the Sopranos.

But to return – finally – to our Roman churches. Bishop Juvenal gave a priceless relic to the then Empress, namely the chains reportedly used to bind St. Peter, as recorded in the Book of Acts. Access to such treasures reminded everyone who cared to listen of the apostolic origins of the see of Jerusalem, while the physical existence of the chains provided a direct connection to the most powerful of saints. That empress’s daughter, our Eudoxia, presented them in turn to the Roman Popes, who duly verified them: According to legend, “when Leo compared them to the chains of St. Peter’s final imprisonment in the Mamertine Prison, in Rome, the two chains miraculously fused together.” The splendid new church, the Basilica Eudoxiana, was built by the late 430s.

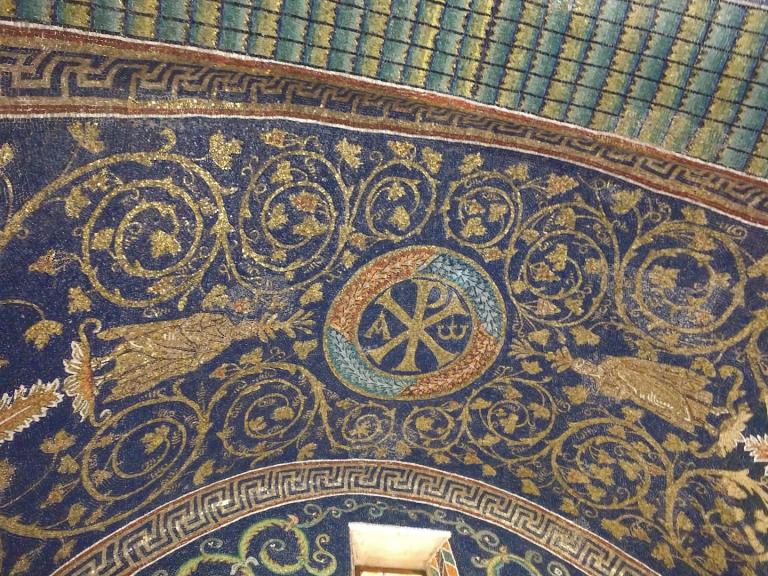

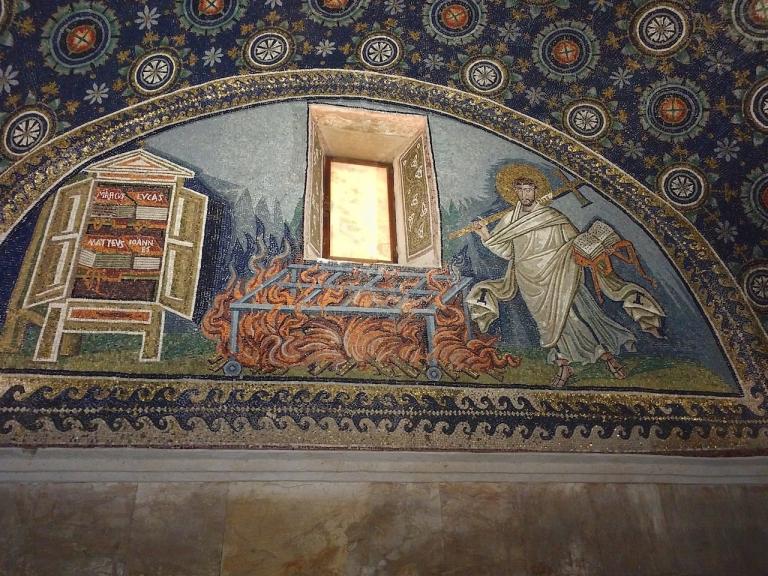

The other spectacular church of this time was Santa Maria Maggiore, again a product of Sixtus and Leo. This church appeared in the early 430s, immediately following the Council of Ephesus, and it was in fact one of the first anywhere built specifically to honor the Blessed Virgin. It preserves a stellar array of fifth century mosaics, which did much to form later artistic images of Mary as Mother of God, Theotokos. Some of these surviving mosaics depict familiar Old Testament themes, of the kind famous from the study of typology – of how the Old Testament prefigures the New. The image for instance of the Egyptians in the Red Sea was a common image prefiguring Baptism.

After the Renaissance, we always think of St. Peter’s Dome as the visual symbol of the Vatican, and of the papacy, but this was not true in earlier eras. The Popes were more closely linked to St. John Lateran, and Santa Maria Maggiore was also critical to Rome’s spiritual life.

So let me offer this as an introduction. This was a church deeply bound to imperial patronage and power, seeking to proclaim Rome as the capital of a global spiritual empire, reproducing and yet replacing the older pagan world. The City of God idea is commonly associated with St. Augustine, who died in 430, as his city of Hippo was withstanding a Vandal siege. This was a church that looked to apostolic precedent, and to the spiritual power associated with martyrs. It also delved deeply into the Old Testament, as the foundation story, the back-story, of the whole Christian world view. The Christian vision was thoroughly sacramental, with a powerful belief in the spiritual value of material things, such as relics. Very fortunately for us, this church depicted its ideas and ideologies explicitly, floridly, in art – above all in mosaics.

What survives from Rome is deeply impressive. But it is only the slightest shadow of what we find in Ravenna, the royal palatium of which city appears in this photo above.

What survives from Rome is deeply impressive. But it is only the slightest shadow of what we find in Ravenna, the royal palatium of which city appears in this photo above.

More next time.

CREDITS: I took all the photos myself with my cellphone.