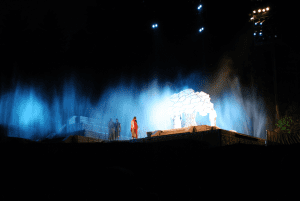

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints recently announced that the Hill Cumorah Pageant will end after its 2020 production. The Church stated that “larger productions, such as pageants, are discouraged,” as it further shifts its focus to “home-centered, Church-supported curriculum that contributes to joyful gospel living.”

I grew up outside of Rochester, New York, and have been familiar with the Hill Cumorah Pageant for quite some time. My wife and I attended a performance at the pageant in 2002, one of the first things that sparked my ongoing interest in the Latter-day Saint.

Here to put this decision into historical context, and explain how integral pageants have been to Mormon religious culture over the past century is Megan Sanborn Jones, professor of theatre at Brigham Young University. Her very timely book is Contemporary Mormon Pageantry: Seeking After the Dead, just published by the University of Michigan Press.

For those who know nothing about Mormon Pageantry, how important have pageants within the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints? How many people have been participating in them and attending them each year?

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints officially produces seven pageants and one religious musical on a regular schedule in venues across the United States and in England. These performances alone qualify the Church as the largest producer of organized religious theatre in America, and they don’t count the countless smaller skits, plays, and pageants produced by regional and local congregations. I believe that Mormon theatre is the most organized, elaborate, and extensive example of religious theatre in the United States today.

Mormon pageant experiences are carefully constructed, fully immersive events that remember, honor, and celebrate Mormon scripture and history. They have been in production for decades—beginning variously in the 1920s through the 1960s and running annually until today (with a brief hiatus during WWII.) They are an integral material and spiritual part of the communities where they are performed. For the Church, support for these pageants signals an ongoing commitment to the power of performance to strengthen the testimonies of participants and to spread the gospel to audiences.

At any one given spring/summer season, the five annual pageants (Mesa Easter, Hill Cumorah, Manti, and Nauvoo/British pageants) and one of the biennial pageants (Martin Harris or Castle Valley) will involve roughly 4000 members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints either on stage or as volunteers to help produce the production. About 240,000 attend one of these pageants.

You write in your introduction that you have been a “participant-observer” of Mormon pageants, studying them while you contributed to and helped create them. How did you come to both study and participate in Mormon pageants?

I was introduced to the idea that I could study Mormon performance in a graduate seminar in my doctoral program at the University of Minnesota. I will be forever grateful to my professor, Dr. Tamara Underiner, who encouraged me to examine my own culture and faith. This initial work led to my career-long examination of the representation of Mormon on the American stage. I have written about 19th century anti-Mormon melodrama, handcart trek reenactments, the history of Mormon playwrighting, Mormon contestants on So You Think You Can Dance, and eventually (inexorably?) I moved to study pageants.

For me, the pageants performance is as much, if not more, about those who make them (participants) than it is about who they are made for (audience.) I think the best way to learn about those who are making theatre is to make it alongside them, so as much as possible I spent time both as a participant—attending devotionals, eating with the cast members, working on the crew, and interviewing dozens of people. I’m so grateful to the several pageants who welcomed me and invited me to participate, and to the countless participants I spoke to over the years I gathered research.

You write that in the early twentieth century, pageants were a significant part of American culture in general. “It is a form that died out nearly a hundred years ago,” you write, “with this one exception: Mormons keep performing them.” Why?

This is a question that first got me interested in the topic of pageants. If the grand style of American new pageantry has been on the cusp of death for a century, why did Mormons keep it alive for so long? While I am not privy to any of the decision-making in regards the continuance (or recent cancellation) of pageants by Church officials in Salt Lake City, I have some ideas about why I think they have been the public performance genre of choice for the Church.

First, the ongoing production of pageants reveals the power and importance of tradition to Mormon culture. Next, the form of pageants is an aesthetically safe, or “good,” live performance that resolves concerns for a religious group that is invested in theatre but committed to avoiding the potential evils of representation that abound in popular culture today. Finally, the production requirements of pageants (spectacular, morally clear, and emotionally evocative) are particularly effective in furthering the purposes of the Church. In the final analysis however, I think the LDS Church has continued to pageants because they were seen as being effective in whatever goal was being set through production.

The subtitle of your book is so fascinating. When I think of Latter-day Saints Seeking after the Dead, I think of Family History Centers and temple work. How do Mormons seek after the dead through pageants?

First, pageants are built near the dead, on holy ground. For Mormons, holy ground includes historic sites where the dead once lived, temples where the dead can commune with the living, and America as a promised land, worth defending to the death. Pageants also perform the dead when pageant actors proxy for those who are being reenacted on the stage. This proxy performance is materialized through daily acts of devotion in which actors focus on being better people in real life. Rather than just creating a character that approximates the historical past, pageant participants take their spiritual self-improvement onto the stage. Proxy performance is expressed in a particular acting style that foregrounds sincerity of belief and is embodied through repeated ritual gestures that encode faith on the bodies of the participants, both living and dead. Finally, Mormon pageant audiences perform with the dead as they engage the aid of the Holy Ghost to help discern truth and bear witness of it to others. Pageant audiences feel the Spirit through the spectacle of pageantry. They also are inspired by the spirits of the dead who are engaged in working towards their own redemption.

In Mormon pageantry the dead are sought (and found) by the righteous spirits of the performers and by the Holy Spirit that invests their dramatization of the past with immediacy. Considering the performances from the position of faith and with the inspiration of the Spirit transforms what is being produced into something more than the aesthetic appeal of the production. Pageant participants put care into crafting acting styles, composition, music selection, and set and costume design that open a space to feel the Spirit. The pageants shape and share the past, evidence the ineffable in the present, and promise great things for the future for audiences on both sides of the veil.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints recently announced that it is ending some pageants (most notably, perhaps, the Hill Cumorah Pageant) and reassessing the future of others. Why?

The recent announcement that the Church would be reevaluating the future of pageant performance took many by surprise. I spent most of the weekend following the announcement scouring news sources and social media for clues as to why this change was introduced, as no official explanation was or has since been provided. Several recurring explanations emerged on various platforms: the Church cancelled pageants because they are so dated; because they are no longer effective as missionary tools; because they are racist; because they are available to only a fraction of the Church membership; because they are so American, because they exhaust the resources of the local congregations that host them; or (most often) because they are too expensive. I can see reason in all of these possible explanations. However, not one of these points is new. The pageants have long (for over thirty years) been expensive, narrowly-focused American expressions of faith and history performed in an outmoded style replete with problematic representations of indigenous nations. So for me, the question is less why, but why now?

I think that the leadership Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are not cancelling pageants because there is anything wrong with pageants, any more than I think that the Church cancelled home teaching, High Priest quorums, or the Boy Scouts of America because there was anything “wrong” with those programs. The leadership of the Church is clearly embarking on an expansive and exhaustive revision of the relationship between public and private worship. For me, pageants are just one of the many formal Church programs that have been—and will continue to be—reevaluated as part of the new home- and family-centered, church-supported model of gospel engagement.

Thanks, Megan!