As Philip considers his fascinating series on the year 1918, I thought I’d jump in long enough to take note of one more religious legacy of World War I: the holy day celebrated tomorrow. For the 20th century notion of dedicating one Sunday each autumn to Christ the King emerged out of the Catholic Church’s ongoing wrestling with the worst war to that point in European history.

One month into that war, Benedict XV began his papacy. Protestant leaders in England and Germany didn’t shy away from the language of holy war, but the new pope — spiritual leader of millions on both sides — was horrified:

On every side the dread phantom of war holds sway: there is scarce room for another thought in the minds of men. The combatants are the greatest and wealthiest nations of the earth; what wonder, then, if, well provided with the most awful weapons modern military science has devised, they strive to destroy one another with refinements of horror. There is no limit to the measure of ruin and of slaughter; day by day the earth is drenched with newly-shed blood, and is covered with the bodies of the wounded and of the slain. Who would imagine as we see them thus filled with hatred of one another, that they are all of one common stock, all of the same nature, all members of the same human society? Who would recognize brothers, whose Father is in Heaven? Yet, while with numberless troops the furious battle is engaged, the sad cohorts of war, sorrow and distress swoop down upon every city and every home; day by day the mighty number of widows and orphans increases, and with the interruption of communications, trade is at a standstill; agriculture is abandoned; the arts are reduced to inactivity; the wealthy are in difficulties; the poor are reduced to abject misery; all are in distress.

“Our advice… remained unheard,” Benedict lamented the following summer, as he again appealed to all combatants to “put an end at last to this horrible slaughter, which for a whole year has dishonoured Europe.” Two years later Benedict’s peace proposal found little support among the Allies or Central Powers, though Philip has argued elsewhere that it now “sounds like an extremely attractive alternative” to the way the war actually finished.

In 1922 Pius XI did like his predecessor and dedicated his first encyclical to the subject of peace:

Since the close of the Great War individuals, the different classes of society, the nations of the earth have not as yet found true peace. They do not enjoy, therefore, that active and fruitful tranquillity which is the aspiration and the need of mankind….

The belligerents of yesterday have laid down their arms but on the heels of this act we encounter new horrors and new threats of war in the Near East. The conditions in many sections of these devastated regions have been greatly aggravated by famine, epidemics, and the laying waste of the land, all of which have not failed to take their toll of victims without number, especially among the aged, women and innocent children. In what has been so justly called the immense theater of the World War, the old rivalries between nations have not ceased to exert their influence, rivalries at times hidden under the manipulations of politics or concealed beneath the fluctuations of finance, but openly appearing in the press, in reviews and magazines of every type, and even penetrating into institutions devoted to the cultivation of the arts and sciences, spots where otherwise the atmosphere of quiet and peace would reign supreme.

In the midst of a “dense fog of mutual hatreds and grievances,” Pius declared the aim of his papacy to be “the re-establishment of the Kingdom of Christ by peace in Christ.” In the 1925 encyclical Quas Primas, he reiterated that “as long as individuals and states refused to submit to the rule of our Savior, there would be no really hopeful prospect of a lasting peace among nations. Men must look for the peace of Christ in the Kingdom of Christ…”

Hence the need for “a special feast in honor of the Kingship of Christ.”

Emphasizing the royal attributes of Jesus was a telling choice for the decade after WWI. When better to reflect on a kingdom “that shall never be destroyed, and shall stand for ever” (Dan 2:44) than in the aftermath of a war that toppled four royal dynasties? But by the same token, placing special emphasis on the kingship of Jesus also suggested the nervousness of a religious hierarchy that had long relied on earthly kings to hold back forces of secularization.

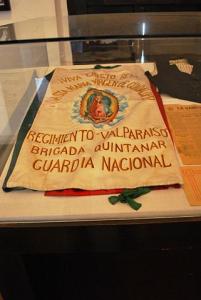

Pius thought that the new feast would “provide an excellent remedy for the plague which now infects society. We refer to the plague of anti-clericalism…” Most notably, the world war sparked a revolution in Russia that replaced a devoutly Christian monarch with the “Red nightmare” of the “atheistic and bolshevistic Communism” that Pius later warned “aims at upsetting the social order and at undermining the very foundations of Christian civilization.” But 1917 also saw Mexico adopt a new constitution containing several articles directly aimed at limiting the influence of the Catholic Church. (Seven years earlier, the overthrow of Portugal’s monarchy had ushered in a similar wave of anticlerical reforms.) The year after Pius instituted Christ the King, the Cristero Rebellion pitted Mexican Catholics against the government of President Calles.

Even if you’re a Protestant who doesn’t accept the magisterial authority of the bishop who founded tomorrow’s feast, you can use Christ the King Sunday to reflect on the political allegiance that, for Christians, trumps all others. You can decide whether you think Pius is right both to emphasize that Christ’s “kingdom is spiritual and is concerned with spiritual things” and yet still has some authority “in civil affairs, since, by virtue of the absolute empire over all creatures committed to him by the Father, all things are in his power.”

You can certainly join Pius in deploring ” those bitter enmities and rivalries between nations, which still hinder so much the cause of peace” and the “insatiable greed which is so often hidden under a pretense of public spirit and patriotism…” Given how our own president has embraced the language of nationalism, I’d especially recommend to your consideration this warning from Pius’ first, most WWI-haunted encyclical:

Patriotism – the stimulus of so many virtues and of so many noble acts of heroism when kept within the bounds of the law of Christ – becomes merely an occasion, an added incentive to grave injustice when true love of country is debased to the condition of an extreme nationalism, when we forget that all men are our brothers and members of the same great human family, that other nations have an equal right with us both to life and to prosperity, that it is never lawful nor even wise, to dissociate morality from the affairs of practical life, that, in the last analysis, it is “justice which exalteth a nation: but sin maketh nations miserable” [Prov 14:34].