John Myles (sometimes written Miles) was among the most important Baptist ministers in seventeenth-century New England.

I first encountered Myles in an essay by my co-blogger Philip Jenkins, who wrote about the role of Miles in opposing the spread of Quaker beliefs and practices in southern Wales.[1] Back in 1649, Myles had gained the pulpit at Ilston, near Swansea, turning its parish church into a magnet for those who rejected infant baptism in the area. As Philip notes, the first in the area to be baptized were women, and many church members came from other parishes and even counties. Often, smaller groups met elsewhere in conventicles, and Myles’s evangelism for his doctrines helped spur the formation of several other Baptist churches in the area.

During the 1650s, Myles was a staunch supporter of Cromwell’s government. After the Restoration, he lost his living at Ilston and soon wisely decided to leave for New England. Myles’s immediate destination is unclear, but as of 1666 Myles was in the Plymouth Colony town of Rehoboth. Other members of the Ilston congregation also emigrated, and the arrival of Baptists in Rehoboth fomented division and controversy.

Rehoboth’s first minister (Samuel Newman) had died in 1663. The town quickly asked Zechariah Symes — a graduate of Harvard and not a Baptist — to preach. When Myles showed up, he also preached on occasion. Soon one faction of the town preferred Myles, and the other preferred Symes.

In terms of extending toleration to dissenters, Plymouth Colony occupied a sort of middle ground between Massachusetts Bay and Rhode Island. Since the early 1640s, Plymouth had allowed individual Baptists to remain within its jurisdiction, as long as they did not establish public meetings or engage in public criticism of the established churches. Along those lines, the first president of Harvard College, Henry Dunster, moved to the Plymouth Colony town of Scituate after his views on baptism made it impossible for him to retain his post and residency in Cambridge. At the same time, in 1650 the colony fined several Baptists for holding Sunday meetings. One of the individuals involved, Obadiah Holmes, left New Plymouth and became a Baptist minister in Newport (and also endured a whipping during a visit to Lynn, Massachusetts).

In Rehoboth, John Myles had substantial support, so much that he gained what New Plymouth’s governor Thomas Prence termed a “major[ity] voate approvable of a Towne gathered together by some Discontents in a promiscuouse assembly of servants.” The exact nature of this assembly remains unclear. Towns typically employed preachers, but churches extended ministerial calls.

A key tenet of the separatist Pilgrims who had founded New Plymouth was that church members possessed the liberty to choose their officers. In this case, Prence thought Myles’s supporters had exercised far too much liberty. “Such a liberty to call minnesthers [ministers],” Prence wrote, “we conceive will hardly bee found in old England or New nor will it stand as wee apprehend.” At the heart of the problem was Myles’s opposition to infant baptism. In other circumstances, a chosen ministerial candidate might hope to win over his opponents, but Myles’s refusal to baptize his opponents’ children was a sure recipe for ongoing conflict. (Of course, the fact that New England’s Congregational ministers would not baptize the children of non-members was in and of itself a recipe for controversy). Prence and likeminded magistrates soon fined Myles for holding an unauthorized public meeting in Rehoboth.

Myles, though, did not leave New Plymouth. In fact, the magistrates proposed a different solution. While they did not want him to stay in Rehoboth, they suggested that his and his followers remove themselves to some place “where they may not prejudice any other church.” In other words, if they left Rehoboth, the colony’s government would leave them alone.

Myles and his Baptists moved a short distance away and founded the town of Swansea. Theirs became the established church, and the town voted Myles a salary. Myles did not exactly find acceptance among his ministerial colleagues in the colony. They complained when he baptized their members, and he complained that they did not accept the legitimacy of his church. At the same time, Myles had much in common with the colony’s Congregational ministers, and when the latter proposed additional measures against Quakers within New Plymouth, they specifically listed standards of orthodox belief in a way that included rather than excluded Swansea’s church. Although Myles briefly pastored a church in Boston during King Philip’s War, he then returned to Swansea and remained there until his death in 1683.

John Myles serves as a reminder of the many ways that communities negotiated the meaning and extent of liberty in colonial New England. During his Ilston years, Myles rejoiced over his church’s “precious liberty, to hold forth the word of God to poor straying souls.” Some Baptists, namely Roger Williams, argued for a very robust religious liberty (in Williams’s case, even for Jews, Turks, and “Antichristians”) and a strict separation between civil governments and churches. Myles did not believe in that sort of religious liberty. He accepted state maintenance in both Wales and Swansea, and he did not believe that civil governments should tolerate Quakers.

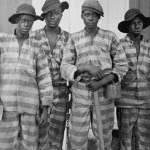

Myles also intersects with another story of liberty in America. As a few historians (including Stephen Roberts) have noted, at some point after his settlement in New Plymouth, Myles became a slaveholder. At the time of his death, he owned some five African slaves: a couple named Peter and Mary, their two children, and another man named Adam. Previously, he had owned at least one other man. In the years after King Philip’s War, many households in New Plymouth included individuals held in bondage: Native captives condemned to slavery or servitude, and a small but growing number of African slaves. Myles’s five slaves made him among the more prominent slaveholders in the colony.

Myles contended for his “precious liberty” in England and Wales, found a new setting in which to exercise it in New England, and denied various forms of liberty to others.

[1] Philip Jenkins, “Infidels, Demons, Witches, and Quakers: The Affair of Colonel Bowen,” Fides et Historia 49 (Summer/Fall 2017): 1-15.