Today I’m happy to welcome to The Anxious Bench Emily G. Wenneborg, a PhD student in philosophy of education at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. While this post is on hymnody, Emily’s research interests include human agency, freedom, and will; language and literacy acquisition; religion, pluralism, and the “culture wars”; and the philosophy and history of homeschooling.

In the past couple of years, I have become something of a religious history buff. This has surprised nobody except myself. Driven by both my doctoral research and my own quest for self-understanding (itself fueled by marrying into a family whose Christian traditions differ significantly from those of my own family-of-origin), my reading has ranged from trying to unravel the complex and wide-ranging effects of the Protestant Reformation to tracing the even more complex splits, mergers, and shifts among Presbyterian and Reformed denominations in America. I have enjoyed putting historical and cultural flesh on names that I had previously received as talismans (J. Gresham Machen, Francis Shaeffer). I now know not only that they are to be revered, but also why (and how far).

In the past couple of years, I have become something of a religious history buff. This has surprised nobody except myself. Driven by both my doctoral research and my own quest for self-understanding (itself fueled by marrying into a family whose Christian traditions differ significantly from those of my own family-of-origin), my reading has ranged from trying to unravel the complex and wide-ranging effects of the Protestant Reformation to tracing the even more complex splits, mergers, and shifts among Presbyterian and Reformed denominations in America. I have enjoyed putting historical and cultural flesh on names that I had previously received as talismans (J. Gresham Machen, Francis Shaeffer). I now know not only that they are to be revered, but also why (and how far).

One happy side-effect of my increasing knowledge of the history of Christianity has been a greater appreciation for the hymns I sing in church each week, in midweek fellowship with my Christian brothers and sisters, and in my personal devotions each morning. I have always loved hymns, both the traditional ones found in the Trinity Hymnal and newer ones written by the likes of Keith and Kristen Getty and Stuart Townend. And I have always known that each hymn has a story; I can recall my dad reading to me from a book of “stories behind the hymns” while I was growing up.

But such stories — or at least my memories of them — tended to focus on individual hymn writers and circumstances of their lives. For example, I have often heard that “It Is Well With My Soul” was written as its author passed by the place where his daughters were drowned, but I knew little of the larger cultural, social, and historical contexts in which this and other hymn writers lived and wrote.

So it has been with genuine pleasure that I have begun to connect the hymns I sing with the Christian history I read about. Typically this involves no more than glancing at the date at the bottom of the hymnal page; but even a date can be informative, when combined with an increasingly rich historical knowledge.

This was brought home to me particularly strongly the other night, when a group of us gathered at the home of one of my “church grandmothers.” We had convened with the explicit purpose of singing older hymns. Our hostess had cousins visiting from Sweden, and wanted us to sing hymns they recognized. Many of these were not hymns I would normally choose to sing, but I love my church family, and I was glad to be there.

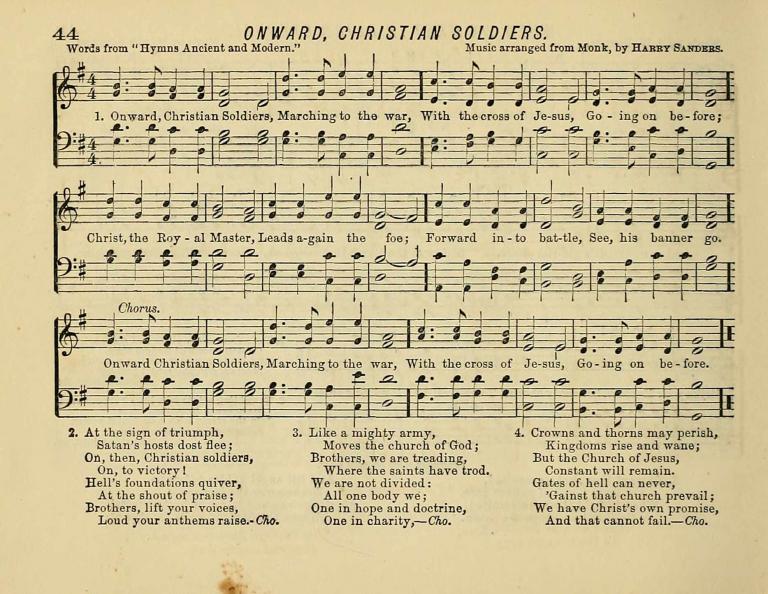

The first hymn whose date caught my eye was “Turn Your Eyes Upon Jesus,” written in 1922. As I sang, “The things of earth will grow strangely dim in the light of his glory and grace,” I smiled to myself, recalling the retreat from engagement in the things of this world and turn toward inner piety of the early twentieth century. Such a hymn could never have been written just a few decades earlier, but in the context of World War I and the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy it must have made perfect sense. My suspicion that the hymn would have sounded foreign to a previous generation of Christian singers was confirmed when we turned to our next hymn, “Onward Christian Soldiers.” I instantly checked the date: 1865. Of course. Somewhat anachronistically, I found myself picturing Confederate and Union troops singing this hymn, each side convinced that it bore the righteous standard of Christianity.[1]

It would be easy to see each of these hymns as in some way fundamentally misguided, confusing its own cultural moment — the self-righteous quest for a Christian nation in the 1860s, retreat in the face of that quest’s defeat in the 1920s — with the eternal truth of Christianity. But to draw this conclusion would be to miss the truth each of these hymns does contain. It is true that the Christian life is one of constant warfare, though our enemy is far more likely to be found in our own skin than in that of our brothers and sisters from across some political, geographic, or racial dividing line. And it is true that we should be constantly fixing our eyes on Jesus, and that as we do so we will come to love Him more than anything in this world, even if loving him also spurs us to love the world and work for its good.

Furthermore, if dwelling on the limitations of older hymns makes us unwilling to learn from them, we will also miss the fact that we ourselves are part of a particular cultural moment, and so are subject to our own over-emphases and blind spots. We need to sing older hymns to remind us of aspects of our shared faith we would otherwise forget.

Singing the hymns of a different generation, much like regularly attending a multi-generational church, is a vital component of the fellowship of the saints. And we will be more able to learn from these older saints and their songs as we understand more of their history, of the particular cultural moment that caused them to write and to sing as they did.

In this way, old hymns and the history of Christianity can work together to deepen our love for Christ’s church.

[1] In looking up the hymn for this post, I learned that it was not even written in the United States, but in England. But the mid-nineteenth-century certainty in the righteousness of fighting for both Christianity and civilization was shared on both sides of the Atlantic.