Like Christianity itself, country music begins with women professing hope in the face of death. The most enduring song from country’s founding family is “Can the Circle Be Unbroken”: a gospel tune about the funeral of a woman, performed by the woman who was country’s first great singer (Sara Carter) to the accompaniment of the woman who was country’s first great guitarist (Maybelle Carter). Yet country music has always been more comfortable with its religious than its feminine origins. So in the week that Ken Burns’ Country Music documentary premiered, it seems appropriate that country’s #1 album was The Highwomen, featuring singer-songwriters Brandi Carlile, Amanda Shires, Maren Morris, and Natalie Hemby.

Christian themes and symbols pop up in interesting ways on a project that takes inspiration from an Eighties all-male supergroup that included Johnny Cash, Maybelle Carter’s gospel-loving son-in-law. “Jesus, he loves his sinners,” sing Carlile and Hemby, with backing from Sheryl Crow, “and heaven is a honky tonk.” (In the process, they seamlessly fuse the “Sunday morning” legacy of the Carter Family with the “Saturday night” strain inherited from country’s other founder: Jimmie Rodgers.) The album-closer is set in the border town of Laredo, where “the echoes of the church bells that were swingin’ / Could be heard from Guadalupe Market Square.”

But most striking is the opening track, which gives the album and group its name. Paying tribute to the signature song that Jimmy Webb wrote for Cash et al., “Highwomen” features four women (Carlile, Shires, Hemby, and guest vocalist Yola) singing about four other women whose spirit survives them.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kerzNA6fSc4

At least two of the song’s deaths happen at the hands of outraged Christians. In verse two, Shires tells of a 17th century New England girl with the spiritual gift of healing; she “heard ‘witchcraft’ in the whispers” and knew her “time had come.” Then in the remarkable fourth verse, sung by Hemby, a woman on a later American frontier takes up her Cross to proclaim the Gospel:

I was a preacher

My heart broke for all the world

But teaching was unrighteous for a girl

In the summer, I was baptized in the mighty Colorado

In the winter, I heard the hounds and I knew I had been found

And in my Savior’s name, I laid my weapons down

But I am still around

After listening to that verse about a dozen times, I decided to ask the Twitterverse if it was inspired by a particular woman in American religious history. Amazingly, one of the song’s writers responded:

https://twitter.com/brandicarlile/status/1174134365606928384

I didn’t press my luck and ask which women had inspired the composite, but I did decide to research the question: How risky was it for American women to preach at earlier times in history? In addition to emotional abuse, did they suffer physical violence from fellow Christians who insisted that “teaching was unrighteous for a girl”?

Here I don’t think there’s a better place to start than Catherine Brekus’ 1998 book, Strangers and Pilgrims: Female Preaching in America, 1740-1845.

(To be fair, Brekus is looking at a part of the country — and, likely, time period — different from what’s in “Highwomen.” But I suspect the reference to “the mighty Colorado” is mostly a nod to the Waylon Jennings verse in the original song: his dam builder slipped and fell into the same river. Anyway, the dangers facing women preachers are not confined to any single time and place.)

(To be fair, Brekus is looking at a part of the country — and, likely, time period — different from what’s in “Highwomen.” But I suspect the reference to “the mighty Colorado” is mostly a nod to the Waylon Jennings verse in the original song: his dam builder slipped and fell into the same river. Anyway, the dangers facing women preachers are not confined to any single time and place.)

Starting with Harriet Livermore’s 1827 sermon on 2 Samuel 23:3 in the U.S. House of Representatives (!), Brekus recovers the stories of more than a hundred evangelical women who preached between the start of the First Great Awakening and the collapse of William Miller’s movement during the Second Great Awakening — a movement that evolved into Seventh-Day Adventism under a woman who had started preaching in late 1844. “Like Livermore,” Brekus writes, “many of these women were belittled as eccentric or crazy, but they repeatedly insisted that God had called them to preach the gospel as his ‘laborers in the harvest’ [Matt 9:38]. Outspoken, visionary, and sometimes contentious, they defended women’s right to preach long before the twentieth-century battles over female ordination” (3).

Starting with the early Quaker women who “posed a double threat to Puritan orthodoxy,” these preachers faced hostility from Christian men who shared “the Puritans’ darkest fears about the dangers of uncontrolled female speech” (30). When Ann Wilkinson was attacked with stones and brickbats after preaching in Philadelphia in 1782, it was “a rare episode of violence,” but “the commotion symbolized the animosity she often faced as a woman in the pulpit.” About the same time, the Shaker founder Ann Lee toured New England and was not only “accused of being a witch… but she was repeatedly threatened, harassed, and even beaten by angry mobs” (91). In a 19th century Shaker account of Lee, her followers see how her “stomach and arms were beaten and bruised black and blue… and indeed it was not to be wondered at, considering how much she had been beaten and dragged about.” Lee concludes, weeping, “I have been like a dying creature.”

Even when they escaped violence in public, some women preachers endured it at home. Elleanor Knight fully took up the mantle of preacher in the 1830s only when she left an alcoholic husband prone to “fits of rage” who resented her growing spiritual authority within their Baptist church. Brekus notes at least three other women preachers who suffered domestic violence, while still more were disowned by their families.

The risk was even greater when women preachers not only questioned patriarchy but white supremacy. White abolitionists like Abby Kelley and Fanny Wright inspired particularly vicious responses; when the latter preached against slavery in New York City, “hecklers broke a windowpane, threw stinkbombs, and set fire to a barrel of turpentine” and “a newspaper editor cursed her as ‘a bold blasphemer, and a voluptuous preacher of licentiousness’” (279). With such incidents in mind, Catherine Beecher — sister of Harriet Beecher Stowe — encouraged women to seek social reform by private influence and stay out of the public square, where they risked “the ungoverned violence of mobs[.]”

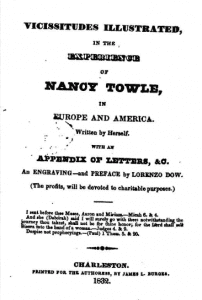

(Not all responded by “[laying their] weapons down.” Infuriated by a male preacher who told her to “stay at home,” Nancy Towle “looked forward to the day when God would ‘raise up a host of female warriors’ to avenge the persecution of women like her. A popular preacher in the 1820s and 1830s who published a memoir called Vicissitudes Illustrated, Towle maintained that the “great, and marvellous things, the Lord has wrought for me… He will not suffer, to be buried in the dust.”)

(Not all responded by “[laying their] weapons down.” Infuriated by a male preacher who told her to “stay at home,” Nancy Towle “looked forward to the day when God would ‘raise up a host of female warriors’ to avenge the persecution of women like her. A popular preacher in the 1820s and 1830s who published a memoir called Vicissitudes Illustrated, Towle maintained that the “great, and marvellous things, the Lord has wrought for me… He will not suffer, to be buried in the dust.”)

Far greater danger loomed for African American women who dared to preach, like Rebecca Jackson, who encountered a group of Methodist ministers who talked openly of stoning or burning her to death. One of the best-known of these Strangers and Pilgrims is Zilpha Elaw, a free black woman influenced by Quakers and Methodists, who

once preached in front of a group of angry white men who stood listening to her “with their hands full of stones.” On another occasion, she was taunted by “an unusually stout and ferocious looking man” who circled the pulpit as if he intended to strike her. Fortunately, none of these men ever harmed her, but she knew that she put herself at physical risk each time she appeared in public. (272)

Elaw felt “[t]orn between her desire to speak and her fear of persecution,” but decided that she “had no option in the matter,” for “No ambition of mine, but the special appointment of God, had put me in the ministry.” It’s a powerful theme that recurs in a book about Christian women who persevered in their commitment to what they understood to be God’s call on their lives. “I have had to endure much persecution,” Elleanor Knight admitted in her 1839 memoir, but she refused to be dissuaded from her conviction that “God has given me authority to labor… to advance the cause of Christ.” Even faced with the risk of death, Elaw, Knight, and other women preachers continued to proclaim hope in their Savior.