He was the first student to ever visit my office.

I wasn’t expecting him to visit. In fact, I wasn’t expecting anybody to visit. I wasn’t holding official office hours that day. My office was nearly impossible to find, set apart from the main corridor and hidden in the back corner of the building. And I was a new professor, only a few weeks into my teaching career. The students barely knew me, and I barely knew them—or anything, for that matter. I didn’t even know how to use the campus library yet.

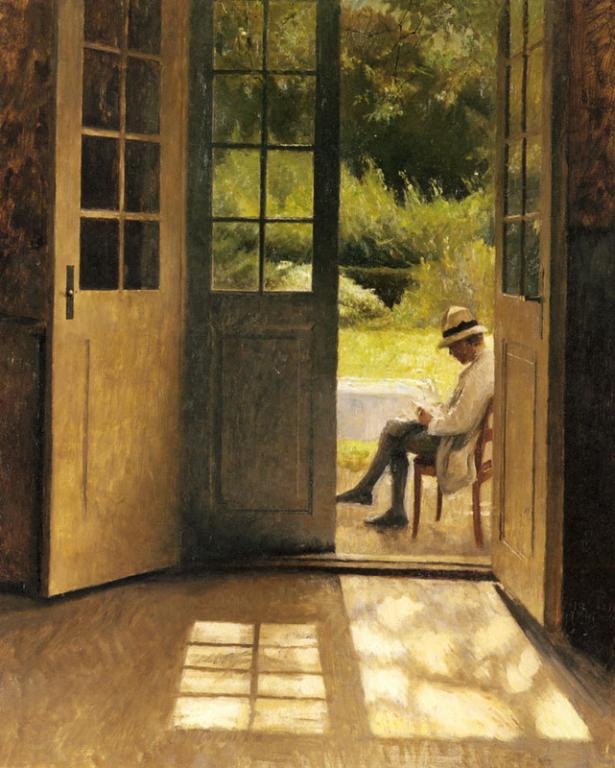

But my door was open—it always is—and perhaps that’s the reason why Paul* arrived unannounced at my office that afternoon. My door was open, and I was present.

Paul greeted me hello, and he parked himself in the chair beside my desk. I offered him tea, and we began to chat about the warm weather and upcoming class assignments. The conversation seemed relatively normal until suddenly, mid-sentence, he fell silent and slumped over.

I called his name; Paul didn’t respond. I poked his arm, then shook him forcefully by the shoulder, but still he remained unresponsive. Panicked, I called the department secretary down the hallway. She rushed to my office, attempted unsuccessfully to rouse him, and called the college’s public safety officers for help. They arrived quickly and brought him to the health clinic on campus.

I received a phone call from a campus police officer a few hours later. Paul hadn’t smelled like alcohol, the officer said, but did I know if he had been doing drugs? Did I know where he had been before he arrived at my office? And why did he come to my office? It was the height of the opioid epidemic, a crisis that had struck this community particularly hard, and I understood the weight of the officer’s questions. But I had no answers. “My door was open,” I said. “He just showed up.”

Paul eventually returned to school, but his troubles continued. In the middle of class one morning, Paul stood up suddenly and stumbled toward the front of the classroom. He didn’t feel well, he announced to everybody, and that was clear: his speech was slurred, his steps were unsteady, and unlike last time, he seemed belligerent. I ended my lecture, and I steered Paul through the crowded hallway and up to my office. Once again, the department secretary came to my aid and called public safety for help. The officers arrived—the same officers from earlier that fall—and removed Paul, once again, from my office to bring him to the health clinic.

Despite these harrowing incidents, I genuinely liked Paul. He was an inquisitive and insightful student. Throughout the fall, he continued to visit my office regularly, and on his good days, he told me about books he had read, songs he had written, and venues where he had performed. He was troubled, yes, but also eager to continue his education. He explained that he was motivated to go to college to set a good example for his family. At least once during every conversation, he pulled out his phone and, beaming with pride, showed me new pictures of his infant. The experience of going to school while also being a parent was a challenge I understood well—I, too, had continued my education while raising a child—and we shared stories about these responsibilities. For the most part, Paul faced these challenges well. He worked hard, and he passed my class with a good grade. When I failed to see him at my office the next semester, I assumed it meant that he had gone on to take other classes and that he had other professors’ office hours to attend. I had high hopes for him.

Over a year later, however, I received a message from another student, a woman who had been in my class that first semester. “Professor, do you remember Paul?” she wrote. “I’m sorry to tell you, but he died.”

Even before I started my first tenure-track job, well-meaning mentors advised me to do everything possible to protect my time. Tenure depends on research and publications, they said, so shut your door so you can do your most important work. Reinforcing their advice were professional productivity experts, evangelists of “deep work” urging people to set aside long periods of time to block out the rest of the world—again, to make it possible to do the most important work.

After having Paul as a student, though, I’ve found myself reconsidering this advice. What precisely is the most important work?

I’ve not only been rethinking the work that I should be doing, but the work that my students should be doing. On the front page of every syllabus, I diligently list the learning objectives of my courses: that by the end of the semester, students should know the causes and consequences of Chinese Exclusion, for example, and be capable of writing a historical essay based on primary sources. I work hard every semester to build my students’ knowledge and skills, using all the tools and instructional techniques my training in education gave me.

But while I want my students to learn, more than anything else, I simply want them to live.

We live and work today in era defined by multiple ongoing and overlapping crises. Paul opened my eyes to the ravages of the opioid epidemic, but other students of mine have struggled with mental health problems, gender-based violence, domestic abuse, vulnerable immigration status, poverty, hunger, homelessness, and enduring and systemic racism, sexism, and homophobia. Institutions of higher education have found many creative and effective ways to respond to the needs of students, and I’m grateful for that.

But colleges and universities must also acknowledge the work that professors do, recognizing that we not only research, write, and teach, but also serve as trusted adults to whom students turn when they’re in trouble. Faculty are often on the front lines of these crises—a fact that the work culture of academia tends to downplay.

The reality is that many professors do a tremendous amount of this type of invisible labor—especially those of us who, like me, are young, female, and people of color. The work of mentoring and caring falls disproportionately on our shoulders. Rather than seeing this labor as a burden, though, I embrace these responsibilities with a sense of mission, purpose, gratitude, and joy. For those of us who come to the professoriate from the margins, we feel a particularly deep responsibility to serve our students, perhaps because we recognize ourselves in our students.

For these reasons I feel uncomfortable with the constant advice I’ve received to close my door and focus solely on my research and my writing. Boundaries are important, yes, and publications matter. But my greatest priority is to be present for the people around me, especially in moments of suffering, whether I expect these people to show up at my office or not.

Because I do much of my email during my long commute to work, I often dictate messages on my phone, which seems to play a prank on me every now and then: instead of “Professor Borja,” my phone transcribes my name as “Pastor Borja.” The mistaken change in title always makes me laugh, and I like to use the occasion to joke about the similarities between a pastor and a professor. Like a pastor, I spend many hours developing an inspiring and thought-provoking lecture, with grandiose visions of transforming hearts and minds. In reality, I usually end up giving my lecture to an audience that’s barely able to stay awake—and I’m simply grateful that they showed up.

I usually draw parallels between professors and pastors in jest, but there’s some truth to it. What my student Paul taught me is that there are indeed pastoral dimensions to the work of a professor. Quite often, my most important work is to listen, to care, to be present in pain and suffering, and to show up, in case they show up. Put simply, my greatest responsibility is to love.

And because my heart is open, my office door remains open.

* Name has been changed.